Does Ozempic help IBS? This question arises frequently as patients seek relief from irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Ozempic (semaglutide) is a GLP-1 receptor agonist licensed in the UK exclusively for type 2 diabetes management, not for IBS treatment. Whilst Ozempic affects gut motility and can cause gastrointestinal side effects, there is no clinical evidence supporting its use for IBS. This article examines the relationship between Ozempic and IBS symptoms, clarifies regulatory guidance, and outlines evidence-based IBS treatments recommended by NICE for UK patients.

Summary: Ozempic is not licensed or recommended for IBS treatment in the UK and lacks clinical evidence supporting its use for irritable bowel syndrome.

- Ozempic (semaglutide) is a GLP-1 receptor agonist licensed exclusively for type 2 diabetes management in the UK.

- The medication slows gastric emptying and commonly causes gastrointestinal side effects including nausea, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain.

- No regulatory body (NICE, MHRA) recognises Ozempic as an IBS treatment, and high-quality clinical evidence is lacking.

- Patients with IBS taking Ozempic for diabetes may experience worsened gastrointestinal symptoms requiring dose adjustment or alternative medications.

- Evidence-based IBS treatments include dietary modification (low FODMAP diet), antispasmodics, loperamide for diarrhoea, and linaclotide for constipation-predominant IBS.

- Patients should consult their GP or diabetes specialist before using Ozempic off-label and pursue NICE-recommended IBS management strategies instead.

Table of Contents

What Is Ozempic and How Does It Work?

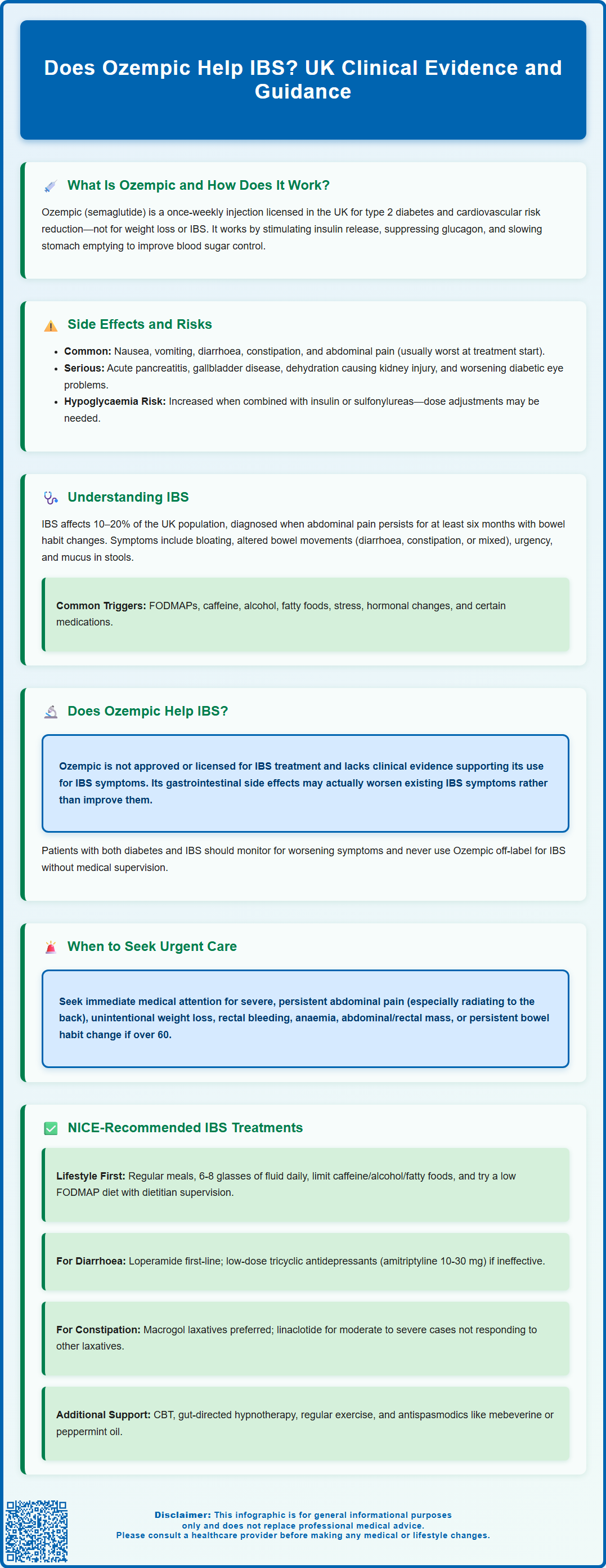

Ozempic (semaglutide) is a prescription medication licensed in the UK for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. It belongs to a class of drugs known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Ozempic is administered as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection and works by mimicking the action of the naturally occurring hormone GLP-1, which plays a crucial role in glucose regulation and appetite control.

The mechanism of action of Ozempic involves several physiological processes. Firstly, it stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner, meaning insulin is released only when blood glucose levels are elevated. Secondly, it suppresses the release of glucagon, a hormone that raises blood sugar levels. Thirdly, semaglutide slows gastric emptying, which delays the rate at which food leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine. This delayed gastric emptying contributes to improved post-prandial (after-meal) glucose control and promotes satiety, which may lead to weight reduction, although Ozempic is not licensed for weight management in the UK.

In the UK, Ozempic is licensed by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) specifically for glycaemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. The UK licence also recognises its benefit in reducing major adverse cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes who have established cardiovascular disease.

Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, and abdominal pain. These side effects are typically most pronounced during the initial titration phase and often diminish over time. Important safety considerations include risk of acute pancreatitis (seek urgent medical attention for severe, persistent abdominal pain), gallbladder disease, dehydration leading to acute kidney injury with severe gastrointestinal effects, and potential worsening of diabetic retinopathy, particularly with rapid improvement in blood glucose control. Caution is advised in patients with severe gastrointestinal disorders, including gastroparesis. The risk of hypoglycaemia increases when Ozempic is used with insulin or sulfonylureas, and doses of these medications may need adjustment.

Patients should report persistent or severe gastrointestinal symptoms to their GP or diabetes specialist, as dose adjustment may be necessary. Suspected side effects can be reported via the MHRA Yellow Card Scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk).

Understanding IBS: Symptoms and Triggers

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder affecting approximately 10–20% of the UK population. It is characterised by recurrent abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habits, without identifiable structural or biochemical abnormalities. According to NICE guidelines (CG61), IBS is diagnosed based on clinical criteria when patients experience abdominal pain or discomfort that has persisted for at least six months, alongside changes in bowel frequency or stool consistency.

The primary symptoms of IBS include:

-

Abdominal pain or cramping, often relieved by defecation

-

Bloating and distension

-

Altered bowel habits: diarrhoea (IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), or mixed patterns (IBS-M)

-

Urgency or a sensation of incomplete evacuation

-

Mucus in stools

Symptoms typically fluctuate over time and may be triggered or exacerbated by various factors. Common triggers include dietary components (such as FODMAPs, caffeine, alcohol, and fatty foods), psychological stress, hormonal changes (particularly in women), and certain medications. The pathophysiology of IBS is multifactorial, involving visceral hypersensitivity, altered gut motility, gut-brain axis dysfunction, and changes in the gut microbiome.

Patients experiencing red flag symptoms should be promptly referred for specialist investigation to exclude serious pathology. According to NICE guidance (NG12), these red flags include unintentional weight loss, rectal bleeding, iron-deficiency anaemia, abdominal or rectal mass, persistent change in bowel habit (to looser or more frequent stools) for more than 6 weeks in people aged 60 or over, and a family history of bowel or ovarian cancer.

Initial assessment should include a full blood count, C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and coeliac serology to rule out alternative diagnoses. Faecal calprotectin testing should be considered in patients with recent-onset lower gastrointestinal symptoms where cancer is not suspected, to help distinguish between IBS and inflammatory bowel disease (NICE DG11). Routine colonoscopy is not required in patients with typical IBS symptoms without red flags.

Does Ozempic Help IBS Symptoms?

There is no official link or licensed indication for using Ozempic (semaglutide) in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Ozempic is specifically approved for type 2 diabetes management and is not recognised by NICE, the MHRA, or other UK regulatory bodies as a treatment for IBS. Currently, there is insufficient high-quality clinical evidence to support its use for IBS symptom management.

However, it is important to understand why this question arises. The gastrointestinal effects of Ozempic—particularly its action in slowing gastric emptying and altering gut motility—can produce symptoms that overlap with IBS. Patients taking Ozempic commonly experience nausea, abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea, or constipation as adverse effects. For individuals with pre-existing IBS, these medication-induced gastrointestinal changes could theoretically either worsen or, in rare cases, coincidentally improve certain symptoms, though this would not constitute therapeutic benefit.

Clinical considerations are important for patients with both type 2 diabetes and IBS who are prescribed Ozempic. The gastrointestinal side effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists may be particularly challenging for IBS patients, potentially exacerbating symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, or altered bowel habits. GLP-1 receptor agonists are generally not recommended in patients with severe gastric motility disorders such as gastroparesis. Patients should maintain adequate hydration, especially if experiencing vomiting or diarrhoea, to reduce the risk of acute kidney injury. Urgent medical review is needed for severe, persistent abdominal pain (particularly if radiating to the back), as this could indicate pancreatitis.

Patients should never use Ozempic off-label for IBS without medical supervision. If you have IBS and are considering or currently taking Ozempic for diabetes, discuss any worsening gastrointestinal symptoms with your GP or diabetes specialist. Dose adjustment, slower titration, or alternative diabetes medications may be more appropriate. For IBS management, evidence-based treatments recommended by NICE should be pursued instead.

Alternative Treatments for IBS in the UK

NICE guidelines (CG61) recommend a stepwise approach to IBS management, beginning with lifestyle and dietary modifications before progressing to pharmacological interventions. Treatment should be individualised based on the predominant symptom pattern (diarrhoea, constipation, or mixed) and the impact on quality of life.

First-line management includes:

-

Dietary advice: Patients should be encouraged to eat regular meals, avoid prolonged gaps between eating, drink adequate fluids (aim for 6–8 glasses daily), and limit caffeine, alcohol, and fatty foods. A low FODMAP diet, supervised by a registered dietitian, has strong evidence for symptom improvement and is increasingly recommended in UK practice.

-

Physical activity: Regular exercise can improve overall symptoms and quality of life.

-

Stress management: Psychological therapies, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and gut-directed hypnotherapy, have demonstrated efficacy for refractory IBS.

-

Probiotics: NICE suggests considering a trial of probiotics for up to 4 weeks.

Pharmacological treatments are symptom-specific:

-

For IBS-D (diarrhoea-predominant): Loperamide is first-line for diarrhoea control. If ineffective, tricyclic antidepressants (such as amitriptyline) may be considered for their effects on visceral hypersensitivity and gut motility. Typical starting dose is 10 mg at night, which may be titrated to 20–30 mg as tolerated (note: this is an off-label use). If TCAs are ineffective or not tolerated, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be considered.

-

For IBS-C (constipation-predominant): Laxatives such as macrogols are preferred. Linaclotide, a guanylate cyclase-C agonist, is available on NHS prescription for patients with moderate to severe IBS-C who have not responded adequately to other laxatives (NICE TA318).

-

For abdominal pain: Antispasmodics (such as mebeverine or peppermint oil) can provide symptomatic relief.

Referral to gastroenterology should be considered for patients with refractory symptoms despite optimal primary care management, or when the diagnosis is uncertain. Faecal calprotectin testing should be considered where inflammatory bowel disease is a differential diagnosis and cancer is not suspected. Routine colonoscopy is not required in patients with typical IBS symptoms without red flags.

Patients should contact their GP if symptoms significantly worsen, if new red flag features develop, or if their quality of life is substantially impaired despite treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Ozempic be prescribed for IBS in the UK?

No, Ozempic is not licensed or recommended for IBS treatment in the UK. It is approved exclusively for type 2 diabetes management and should not be used off-label for IBS without medical supervision.

Will Ozempic worsen my IBS symptoms?

Ozempic commonly causes gastrointestinal side effects including nausea, diarrhoea, constipation, and abdominal pain, which may exacerbate existing IBS symptoms. Patients with IBS taking Ozempic for diabetes should discuss any worsening symptoms with their GP or diabetes specialist for possible dose adjustment.

What are the recommended treatments for IBS in the UK?

NICE recommends a stepwise approach including dietary modifications (low FODMAP diet), regular physical activity, stress management, and symptom-specific medications such as loperamide for diarrhoea, linaclotide for constipation, and antispasmodics for abdominal pain.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript