Is intermittent fasting sustainable as a long-term dietary approach? Intermittent fasting (IF) involves alternating between periods of eating and voluntary fasting on a regular schedule. Whilst research suggests it may offer comparable weight loss to continuous calorie restriction, sustainability depends heavily on individual circumstances, lifestyle, and medical history. Common methods include the 16:8 pattern (fasting for 16 hours daily) and the 5:2 diet (restricting calories on two non-consecutive days weekly). This article examines the evidence surrounding intermittent fasting's sustainability, potential health benefits and risks, who should avoid it, and practical strategies for maintaining this eating pattern long-term within the context of UK clinical guidance.

Summary: Intermittent fasting can be sustainable for some individuals when appropriately tailored to lifestyle and medical circumstances, though it is not suitable for everyone and requires careful consideration of individual health factors.

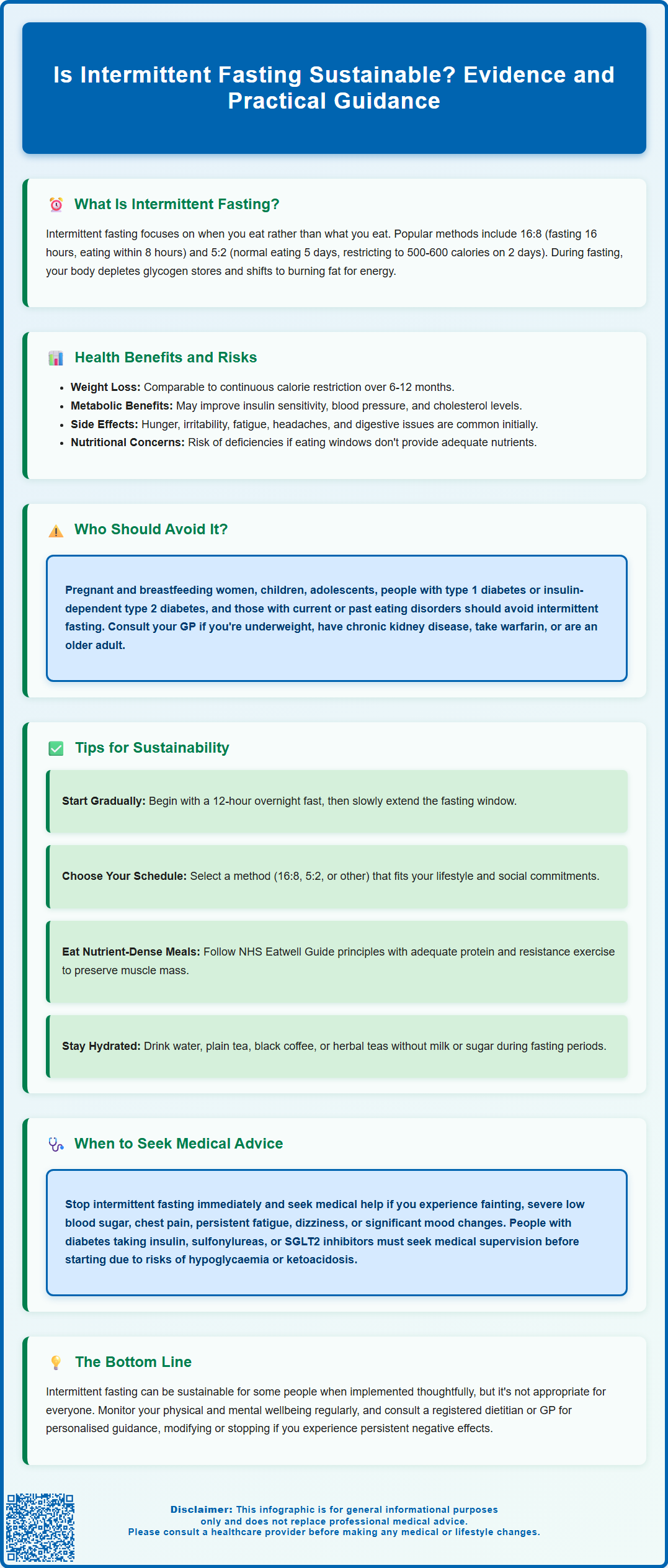

- Intermittent fasting is a dietary pattern alternating between eating and fasting periods, with common methods including 16:8 (16-hour fast, 8-hour eating window) and 5:2 (normal eating five days, calorie restriction two days).

- The approach works through metabolic switching, where the body depletes glycogen stores during fasting and may utilise fat for energy, with insulin levels decreasing to facilitate this process.

- Research suggests intermittent fasting produces weight loss comparable to continuous calorie restriction over 6–12 months, with potential modest improvements in insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular markers.

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women, children, adolescents, people with type 1 diabetes or insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes, and those with eating disorder history should avoid intermittent fasting due to significant health risks.

- Common adverse effects include hunger, irritability, fatigue, headaches, and potential nutritional deficiencies if eating windows do not provide adequate nutrients; medical supervision is essential for those with pre-existing conditions or taking certain medications.

- Sustainability requires gradual implementation, choosing schedules aligned with daily routines, prioritising nutrient-dense meals during eating windows, maintaining adequate hydration, and regular monitoring of physical and mental wellbeing with professional guidance when appropriate.

Table of Contents

What Is Intermittent Fasting and How Does It Work?

Intermittent fasting (IF) is a dietary pattern that alternates between periods of eating and voluntary fasting on a regular schedule. Unlike traditional diets that focus on what you eat, intermittent fasting primarily concerns when you eat. The most common approaches include the 16:8 method (fasting for 16 hours and eating within an 8-hour window), the 5:2 diet (eating normally for five days and restricting calories to approximately 500–600 on two non-consecutive days), and alternate-day fasting (typically allowing about 500-600 calories on 'fast' days).

The physiological mechanism underlying intermittent fasting involves metabolic switching. During fasting periods, the body gradually depletes its glycogen stores and may begin to break down fat for energy through a process called lipolysis. This metabolic shift can vary widely between individuals (from approximately 12 to 36+ hours) depending on diet, activity levels and individual factors. With prolonged fasting, the body may produce ketone bodies, which can serve as an alternative fuel source. Some research suggests fasting might trigger cellular repair processes, including autophagy—where cells remove damaged components—though evidence for this occurring with typical intermittent fasting patterns in humans remains limited.

Intermittent fasting may influence several hormones that regulate metabolism and appetite. Insulin levels tend to decrease during fasting periods, which may facilitate fat utilisation, whilst levels of other hormones may change. These hormonal adjustments, combined with a potential reduction in overall calorie intake, likely contribute to the weight management effects often associated with intermittent fasting. Some evidence also suggests that aligning eating windows with natural circadian rhythms (eating earlier in the day) might offer additional metabolic benefits.

It is important to note that intermittent fasting is not suitable for everyone, and individuals should consider their personal health circumstances before adopting this eating pattern. The sustainability of intermittent fasting depends largely on individual lifestyle, medical history, and ability to maintain the regimen long-term without adverse effects on physical or mental wellbeing.

Health Benefits and Risks of Intermittent Fasting

Research into intermittent fasting has identified several potential health benefits, though it is important to recognise that much of the evidence comes from animal studies or short-term human trials. Weight loss and improved body composition are among the most commonly reported benefits, primarily resulting from reduced calorie intake. Research suggests that intermittent fasting typically produces weight loss results comparable to continuous calorie restriction over 6-12 months. Some studies suggest intermittent fasting may modestly improve insulin sensitivity and reduce markers of inflammation, which could theoretically benefit individuals at risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Some evidence indicates that intermittent fasting may support cardiovascular health by modestly improving blood pressure, cholesterol profiles, and triglyceride levels, though results vary between individuals. Preliminary research has explored potential neurocognitive benefits, but these findings remain speculative in humans and require further investigation through robust, long-term clinical trials before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

Despite potential benefits, intermittent fasting carries several risks and adverse effects that warrant consideration. Common side effects during the initial adaptation period include hunger, irritability, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, and headaches. Some individuals may experience gastrointestinal disturbances, including constipation or changes in bowel habits. There is also concern that restrictive eating patterns could trigger or exacerbate disordered eating behaviours in susceptible individuals. If you're concerned about disordered eating, the NHS and eating disorder charity BEAT offer support and guidance.

Longer-term risks may include nutritional deficiencies if the eating windows do not provide adequate vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients. Some women may experience menstrual irregularities if energy intake becomes inadequate; anyone experiencing cycle changes should consult their GP and consider modifying or stopping their fasting regimen. Additionally, there is no established link between intermittent fasting and improved longevity in humans, despite promising animal research.

Individuals with pre-existing medical conditions should consult their GP before commencing intermittent fasting. People with diabetes taking insulin, sulfonylureas or SGLT2 inhibitors face particular risks of hypoglycaemia or ketoacidosis and require medical supervision. The NHS emphasises that sustainable weight management should prioritise balanced nutrition and gradual lifestyle changes rather than restrictive dietary patterns.

Who Should Avoid Intermittent Fasting?

Certain groups of individuals should avoid intermittent fasting due to increased health risks or potential complications. Pregnant and breastfeeding women require consistent nutritional intake to support foetal development and milk production; fasting periods could compromise maternal and infant health. Children and adolescents should not undertake intermittent fasting, as their growing bodies require regular, adequate nutrition to support physical and cognitive development.

Individuals with type 1 diabetes or insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes face significant risks from intermittent fasting, including dangerous fluctuations in blood glucose levels and increased risk of hypoglycaemia. Those taking sulfonylureas, meglitinides or SGLT2 inhibitors are at particular risk of hypoglycaemia or euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis during fasting. The timing of medication administration and food intake must be carefully coordinated, making prolonged fasting periods potentially hazardous without medical supervision. Those taking medications that require food intake or have specific timing requirements should consult their healthcare provider before attempting intermittent fasting, as altered eating patterns may affect drug absorption and efficacy.

People with a history of eating disorders—including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder—should avoid intermittent fasting, as restrictive eating patterns may trigger relapse or exacerbate disordered eating behaviours. Similarly, individuals with a tendency towards obsessive thoughts about food or body image should approach intermittent fasting with caution. The psychological impact of rigid eating schedules can be detrimental to mental health and recovery.

Other groups who should exercise caution or avoid intermittent fasting include individuals who are underweight or have a history of malnutrition, those with moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease (who should consult renal specialists or dietitians), and people with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) that worsens with fasting, though some may benefit from earlier, smaller meals. Individuals taking warfarin should maintain consistent vitamin K intake and arrange additional INR monitoring when changing eating patterns. Older adults should consult their GP before starting intermittent fasting, as they may be at increased risk of muscle loss (sarcopenia) and nutritional deficiencies.

Anyone experiencing severe adverse symptoms such as fainting, severe hypoglycaemia, chest pain, persistent fatigue, dizziness, or significant mood changes whilst practising intermittent fasting should seek immediate medical attention and discontinue the regimen.

Tips for Making Intermittent Fasting More Sustainable

Sustainability is crucial for any dietary approach to provide long-term health benefits. To make intermittent fasting more manageable, start gradually rather than immediately adopting a strict fasting schedule. Begin with a 12-hour overnight fast (for example, finishing dinner by 8 PM and not eating until 8 AM) and progressively extend the fasting window as your body adapts. This gradual approach minimises adverse effects and allows you to assess whether intermittent fasting suits your lifestyle and wellbeing.

Choose a fasting schedule that aligns with your daily routine and social commitments. The 16:8 method can be adapted to suit individual preferences—some people prefer skipping breakfast and eating between midday and 8 PM, while others may benefit from an earlier eating window (e.g., 8 AM to 4 PM) that better aligns with natural circadian rhythms. The 5:2 approach may suit those who prefer eating normally most days whilst accepting two days of reduced intake. There is no single 'correct' method; sustainability depends on personal preference and practical feasibility.

During eating windows, prioritise nutrient-dense, balanced meals that include adequate protein, healthy fats, complex carbohydrates, and plenty of vegetables, following principles similar to the NHS Eatwell Guide. Adequate protein intake and resistance exercise are particularly important to preserve muscle mass, especially for older adults. Avoid the temptation to overcompensate for fasting periods by consuming excessive calories or nutrient-poor foods. Adequate hydration is essential throughout fasting periods—water, plain tea, black coffee, and herbal teas (without milk or sugar) are generally acceptable as they contain negligible calories. Be aware that caffeine may worsen anxiety or reflux symptoms in sensitive individuals. Some people find that staying busy during fasting periods helps distract from hunger sensations.

Monitor your physical and mental wellbeing regularly. Keep a journal noting energy levels, mood, sleep quality, and any adverse symptoms. If you experience persistent negative effects, consider modifying your approach or discontinuing intermittent fasting. Be prepared to pause your fasting schedule during illness, periods of increased physical activity, or when it interferes with medication timing. Rigid adherence to fasting schedules despite negative consequences is counterproductive and unsustainable.

Finally, seek professional guidance when appropriate. A registered dietitian can help ensure your eating windows provide adequate nutrition, whilst your GP can advise on whether intermittent fasting is appropriate given your medical history and current medications. NICE guidance emphasises that sustainable weight management should be individualised and based on evidence-based approaches that support long-term health rather than short-term results. If you experience any suspected side effects from medicines while fasting, report them through the MHRA Yellow Card scheme. Remember that intermittent fasting is one of many dietary approaches, and what works sustainably for one person may not suit another.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to adapt to intermittent fasting?

Initial adaptation typically takes 2–4 weeks, during which common side effects like hunger, irritability, and fatigue may occur. Starting gradually with a 12-hour overnight fast and progressively extending the fasting window can minimise adverse effects and improve long-term sustainability.

Can I take my regular medications whilst intermittent fasting?

Medication timing and food requirements vary significantly; consult your GP or pharmacist before starting intermittent fasting. Those taking insulin, sulfonylureas, SGLT2 inhibitors, or medications requiring food intake face particular risks and require medical supervision to adjust dosing and timing appropriately.

What can I drink during fasting periods?

Water, plain tea, black coffee, and herbal teas without milk or sugar are generally acceptable during fasting periods as they contain negligible calories. Adequate hydration is essential, though caffeine may worsen anxiety or reflux symptoms in sensitive individuals.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript