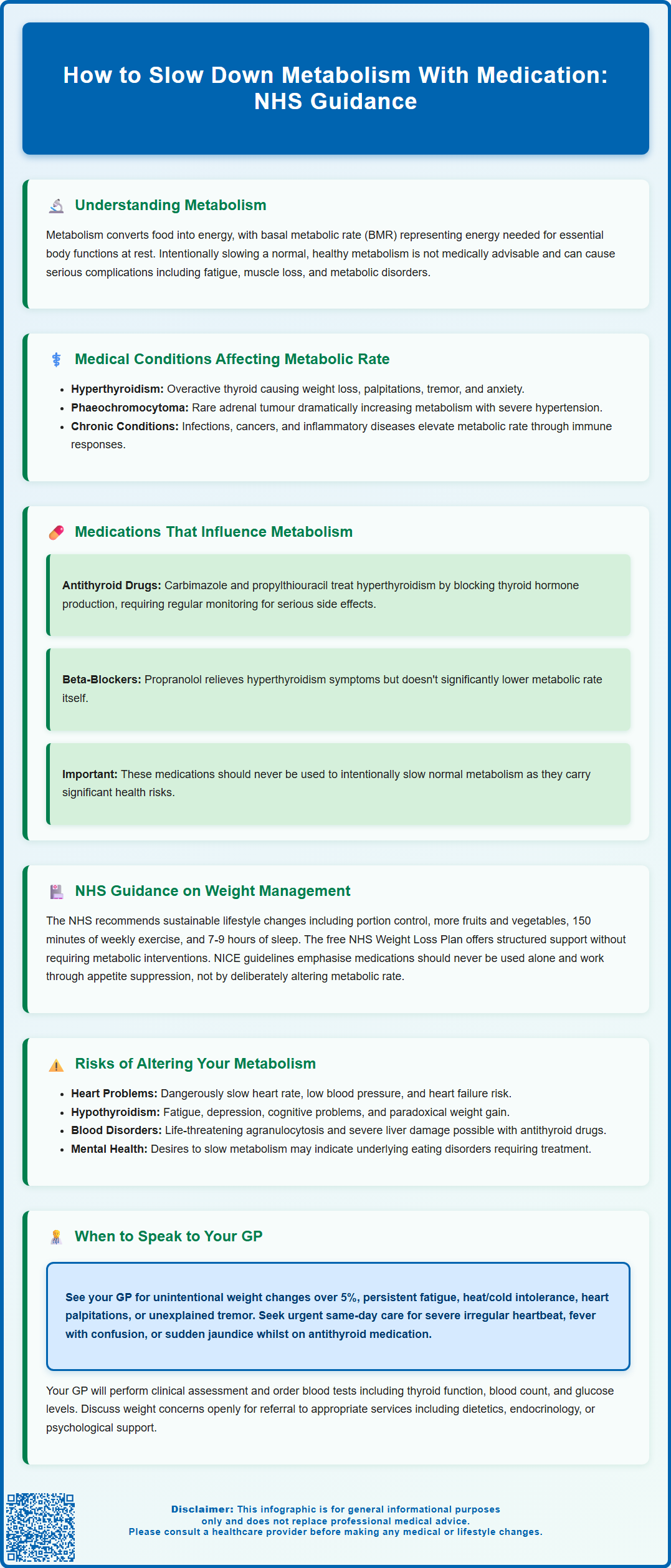

Metabolism encompasses the biochemical processes converting food into energy, with basal metabolic rate (BMR) representing the energy required for essential bodily functions at rest. Whilst most health guidance focuses on increasing metabolism, certain medical conditions such as hyperthyroidism cause abnormally elevated metabolic rates requiring clinical intervention. It is crucial to understand that intentionally slowing a normal, healthy metabolism with medication is not medically advisable and can lead to serious health complications including fatigue, muscle loss, and metabolic disorders. Medications that influence metabolism—such as antithyroid drugs—are prescribed exclusively to treat diagnosed conditions like hyperthyroidism, never for cosmetic weight management. Any consideration of metabolic modification must occur only under specialist medical guidance.

Summary: Medications such as carbimazole and propylthiouracil can slow metabolism by treating hyperthyroidism, but deliberately slowing a normal, healthy metabolism with medication is not medically advisable and carries serious health risks.

- Antithyroid medications (carbimazole, propylthiouracil) inhibit thyroid hormone synthesis to normalise elevated metabolic rate in hyperthyroidism.

- Intentionally slowing normal metabolism can cause cardiovascular complications, endocrine disruption, iatrogenic hypothyroidism, and metabolic syndrome.

- Beta-blockers like propranolol manage sympathetic symptoms of hyperthyroidism but do not significantly lower basal metabolic rate.

- NHS guidance emphasises sustainable lifestyle modifications rather than pharmaceutical metabolic manipulation for weight management.

- Thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4, T3) and specialist endocrinology referral are essential for investigating suspected metabolic disorders.

- Serious adverse effects of antithyroid drugs include agranulocytosis and hepatotoxicity, requiring immediate medical attention if warning signs develop.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Metabolism and Why Someone Might Want to Slow It Down

- Medical Conditions That Affect Metabolic Rate

- Medications That Can Influence Metabolism

- NHS Guidance on Managing Metabolism and Weight

- Risks and Considerations Before Altering Your Metabolism

- When to Speak to Your GP About Metabolic Concerns

- Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding Metabolism and Why Someone Might Want to Slow It Down

Metabolism refers to the complex biochemical processes by which your body converts food and drink into energy. Your basal metabolic rate (BMR) represents the energy your body requires to maintain essential functions such as breathing, circulation, cell production, and temperature regulation whilst at rest. Several factors influence metabolic rate, including age, sex, body composition, genetics, and hormonal status.

Whilst most public health messaging focuses on increasing metabolism for weight management, certain individuals may experience an abnormally elevated metabolic rate that causes unintended health consequences. Hyperthyroidism, for instance, accelerates metabolism significantly, leading to unintentional weight loss, anxiety, tremors, heat intolerance, and cardiac complications. In such cases, medical intervention to normalise metabolism becomes clinically necessary, with the therapeutic goal being restoration to a euthyroid (normal thyroid) state.

It is crucial to understand that intentionally slowing a normal, healthy metabolism is not medically advisable and can lead to serious health complications. The body's metabolic rate exists within a carefully regulated physiological range, and disrupting this balance without medical supervision may result in fatigue, muscle loss, and metabolic disorders. Any consideration of metabolic modification should occur only under specialist medical guidance, typically when treating diagnosed conditions rather than for cosmetic or non-medical weight management purposes.

The concept of deliberately slowing metabolism with medication is fundamentally different from treating pathological conditions that cause hypermetabolism. This distinction is essential for patient safety and informed decision-making.

Medical Conditions That Affect Metabolic Rate

Several medical conditions can significantly alter metabolic rate, requiring clinical intervention. Hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) is the most common condition causing elevated metabolism. The thyroid gland produces excessive amounts of thyroid hormones (thyroxine and triiodothyronine), which accelerate nearly every metabolic process in the body. Patients typically present with weight loss despite increased appetite, palpitations, tremor, heat intolerance, and anxiety. Graves' disease and toxic nodular goitre are common causes.

Investigation of suspected hyperthyroidism includes thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4, and sometimes free T3), and thyroid receptor antibodies (TRAb) where autoimmune disease is suspected. Urgent assessment is warranted for severe symptoms such as atrial fibrillation, severe tachycardia, or confusion with fever (suggesting thyroid storm).

Phaeochromocytoma, a rare tumour of the adrenal glands, secretes excessive catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenaline), dramatically increasing metabolic rate alongside causing severe hypertension, sweating, and palpitations. Investigation includes plasma free metanephrines or 24-hour urinary fractionated metanephrines, with urgent endocrine referral required due to potentially life-threatening complications.

Certain psychiatric conditions may influence metabolism through various mechanisms. Anxiety disorders and mania may increase energy expenditure through heightened sympathetic nervous system activity and altered behaviour patterns. Conversely, some individuals with eating disorders may develop adaptive changes in metabolism, though the primary concern remains nutritional rehabilitation rather than metabolic manipulation.

Chronic infections, malignancies, and inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis can elevate metabolic rate as part of the systemic inflammatory response. The body increases energy expenditure to mount immune responses and repair tissue damage. In these cases, addressing the underlying condition takes precedence over directly targeting metabolic rate.

NICE guidance emphasises that metabolic abnormalities should be investigated thoroughly before treatment. Blood tests including thyroid function tests, full blood count, inflammatory markers, and glucose levels form the foundation of metabolic assessment. Specialist referral to endocrinology is warranted for complex cases or when red flag symptoms are present.

Medications That Can Influence Metabolism

Several medications can influence metabolic rate, though they are prescribed to treat specific medical conditions rather than to deliberately slow metabolism for weight management purposes. Understanding these medications and their mechanisms is important for informed healthcare decisions.

Antithyroid medications such as carbimazole and propylthiouracil are the primary pharmaceutical interventions for hyperthyroidism. Carbimazole works by inhibiting thyroid peroxidase, the enzyme responsible for thyroid hormone synthesis, effectively reducing the production of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). This normalises the elevated metabolic rate seen in hyperthyroidism. Treatment typically begins with higher doses (15-40mg daily), gradually titrating down based on thyroid function monitoring. Common adverse effects include rash and nausea. Serious but rare adverse effects include agranulocytosis (severe reduction in white blood cells), which requires immediate medical attention if signs of infection develop.

Propylthiouracil (PTU) carries a risk of severe hepatotoxicity and is generally second-line in the UK, used particularly in the first trimester of pregnancy or if carbimazole is not tolerated. Carbimazole has teratogenic risks, so PTU is preferred in early pregnancy, with consideration of switching to carbimazole thereafter. Patients should be counselled to report symptoms of liver injury (jaundice, dark urine, right upper quadrant pain) or infection immediately.

Monitoring typically includes thyroid function tests every 4-6 weeks initially, with full blood count and liver function tests as indicated. Both titration and block-and-replace regimens are used in UK practice.

Beta-blockers, particularly propranolol, are often prescribed alongside antithyroid drugs to manage the sympathetic symptoms of hyperthyroidism such as tremor, palpitations, and anxiety. Beta-blockers primarily provide symptomatic relief and do not significantly lower basal metabolic rate. At higher doses, propranolol may inhibit peripheral conversion of T4 to the more active T3, but this is not the main therapeutic effect.

Certain psychiatric medications, including some antipsychotics (olanzapine, clozapine) and mood stabilisers (lithium, valproate), can promote weight gain through mechanisms including increased appetite, insulin resistance, and reduced physical activity. However, these medications are prescribed for serious mental health conditions, and metabolic effects are considered adverse rather than therapeutic.

Corticosteroids such as prednisolone can alter metabolism by promoting protein breakdown, increasing glucose production, and redistributing body fat. Long-term use requires careful monitoring for metabolic complications including diabetes and osteoporosis.

It cannot be emphasised enough that none of these medications should be used to intentionally slow a normal metabolism. They carry significant risks and require specialist prescribing and monitoring.

NHS Guidance on Managing Metabolism and Weight

The NHS provides clear, evidence-based guidance on healthy metabolism and weight management that does not involve pharmaceutical manipulation of metabolic rate. The cornerstone of NHS recommendations focuses on sustainable lifestyle modifications rather than metabolic interventions.

For individuals concerned about weight management, the NHS advises a balanced approach incorporating:

-

Gradual, sustainable dietary changes focusing on portion control, increased fruit and vegetable intake, and reduction of processed foods high in sugar and saturated fats

-

Regular physical activity with at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise weekly, which helps maintain muscle mass and supports healthy metabolic function

-

Adequate sleep (7-9 hours nightly), as sleep deprivation can disrupt metabolic hormones including leptin and ghrelin

-

Stress management, since chronic stress elevates cortisol, which can affect metabolism and weight distribution

The NHS Weight Loss Plan provides structured, free resources including meal plans, exercise guidance, and behavioural support without requiring metabolic manipulation. For individuals with a BMI over 30 kg/m² (or over 28 kg/m² with comorbidities), GPs may refer to specialist weight management services or consider pharmacological interventions such as orlistat, which works by reducing fat absorption rather than altering metabolic rate.

NICE guidance on obesity management emphasises multicomponent interventions addressing diet, physical activity, and behaviour change. Pharmacological treatment is considered only as an adjunct to lifestyle modification, never as a standalone intervention. Importantly, NICE does not recommend medications that deliberately slow metabolism; rather, approved weight management medications work through appetite suppression (such as GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide and liraglutide) or nutrient absorption reduction.

For individuals with diagnosed metabolic conditions such as hypothyroidism, the NHS provides levothyroxine replacement therapy to normalise metabolism, with regular monitoring through thyroid function tests. This represents treatment of pathology rather than cosmetic metabolic manipulation.

Risks and Considerations Before Altering Your Metabolism

Attempting to slow a normally functioning metabolism carries substantial health risks and is not supported by medical evidence or clinical guidelines. Understanding these risks is essential for patient safety and informed decision-making.

Cardiovascular complications represent a significant concern. Medications that reduce metabolic rate often affect heart function, potentially causing bradycardia (abnormally slow heart rate), hypotension, and reduced cardiac output. Beta-blockers, for instance, can precipitate heart failure in susceptible individuals or cause dangerous interactions with other cardiovascular medications such as verapamil or diltiazem. Patients with pre-existing heart conditions face particularly elevated risks.

Endocrine disruption can have far-reaching consequences. Inappropriately using antithyroid medications in individuals with normal thyroid function can induce iatrogenic hypothyroidism, causing fatigue, depression, cold intolerance, constipation, cognitive impairment, and paradoxically, weight gain due to fluid retention and reduced physical activity. Thyroid hormones influence virtually every organ system, and disrupting this delicate balance can affect fertility, bone density, and mental health.

Metabolic syndrome and glucose dysregulation may develop with certain medications that alter metabolism. Some psychiatric medications associated with weight gain increase risks of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and cardiovascular disease. Regular monitoring of glucose, lipids, and blood pressure becomes essential.

Psychological considerations are equally important. The desire to slow metabolism often stems from body image concerns or disordered eating patterns. Addressing underlying psychological factors through appropriate mental health support is crucial. The Royal College of Psychiatrists emphasises that body image concerns warrant psychological intervention rather than metabolic manipulation.

Drug interactions and adverse effects pose additional risks. Antithyroid drugs can cause serious haematological complications including agranulocytosis, requiring immediate cessation and medical attention. Propylthiouracil can cause severe hepatotoxicity. Patients must be counselled about warning signs such as sore throat, fever, mouth ulcers, jaundice, dark urine, or right upper quadrant pain.

The MHRA (Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency) licenses medications affecting metabolism for specific clinical indications. While clinicians may prescribe off-label with appropriate informed consent and monitoring, this should only occur when clinically justified. Patients should report suspected side effects to the MHRA Yellow Card scheme.

When to Speak to Your GP About Metabolic Concerns

Certain symptoms and circumstances warrant prompt discussion with your GP regarding metabolic function. Recognising these indicators ensures appropriate investigation and management of genuine metabolic disorders whilst avoiding unnecessary or harmful interventions.

Seek medical advice if you experience:

-

Unintentional weight changes (loss or gain of more than 5% body weight over 3-6 months without dietary or activity changes)

-

Persistent fatigue that doesn't improve with rest and affects daily functioning

-

Heat or cold intolerance that differs significantly from your usual tolerance

-

Cardiac symptoms including palpitations, irregular heartbeat, or chest discomfort

-

Tremor, anxiety, or agitation that appears without clear psychological triggers

-

Changes in bowel habits, particularly persistent diarrhoea or constipation

-

Menstrual irregularities or fertility concerns potentially related to metabolic dysfunction

-

Mood changes, including depression or anxiety, especially if accompanied by physical symptoms

Seek urgent same-day medical attention for:

-

Severe palpitations or irregular heartbeat

-

Fever with confusion or agitation (possible thyroid storm)

-

Severe headache with palpitations and excessive sweating (possible phaeochromocytoma crisis)

-

Sudden onset of jaundice or severe abdominal pain while taking antithyroid medication

Your GP will conduct a thorough clinical assessment including medical history, physical examination, and appropriate investigations. Initial blood tests typically include thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4, and sometimes T3), thyroid receptor antibodies (TRAb) where autoimmune disease is suspected, full blood count, renal and liver function, glucose, and lipid profile. Depending on findings, further specialist investigations may be warranted.

If you have concerns about weight management, discuss these openly with your GP. They can assess whether your weight concerns are medically justified, screen for eating disorders or body dysmorphia, and provide evidence-based guidance. Referral pathways may include dietetics, specialist weight management services, endocrinology, or psychological support depending on individual circumstances.

For diagnosed conditions affecting metabolism, regular monitoring is essential. Patients taking antithyroid medications require thyroid function tests every 4-6 weeks initially, then less frequently once stable. Any new symptoms or concerns should prompt earlier review.

Remember that your GP is your advocate for safe, evidence-based care. There is no official link between healthy weight management and the need to slow metabolism through medication. Honest, open communication about your concerns—whether physical symptoms or body image issues—enables your healthcare team to provide appropriate, safe, and effective support tailored to your individual needs.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take medication to slow my metabolism for weight management?

No, deliberately slowing a normal, healthy metabolism with medication is not medically advisable and can cause serious health complications including cardiovascular problems, endocrine disruption, and metabolic disorders. Medications that affect metabolism are prescribed only to treat diagnosed medical conditions such as hyperthyroidism, never for cosmetic weight management purposes.

What medications are used to treat an overactive metabolism?

Antithyroid medications such as carbimazole and propylthiouracil are prescribed to treat hyperthyroidism by inhibiting thyroid hormone synthesis. Beta-blockers like propranolol may be used alongside antithyroid drugs to manage symptoms such as tremor and palpitations, though they do not significantly lower basal metabolic rate.

When should I see my GP about metabolic concerns?

Seek medical advice if you experience unintentional weight changes (more than 5% over 3-6 months), persistent fatigue, heat or cold intolerance, cardiac symptoms, tremor, or mood changes. Your GP will conduct a thorough assessment including thyroid function tests and appropriate investigations to identify any underlying metabolic disorders requiring treatment.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript