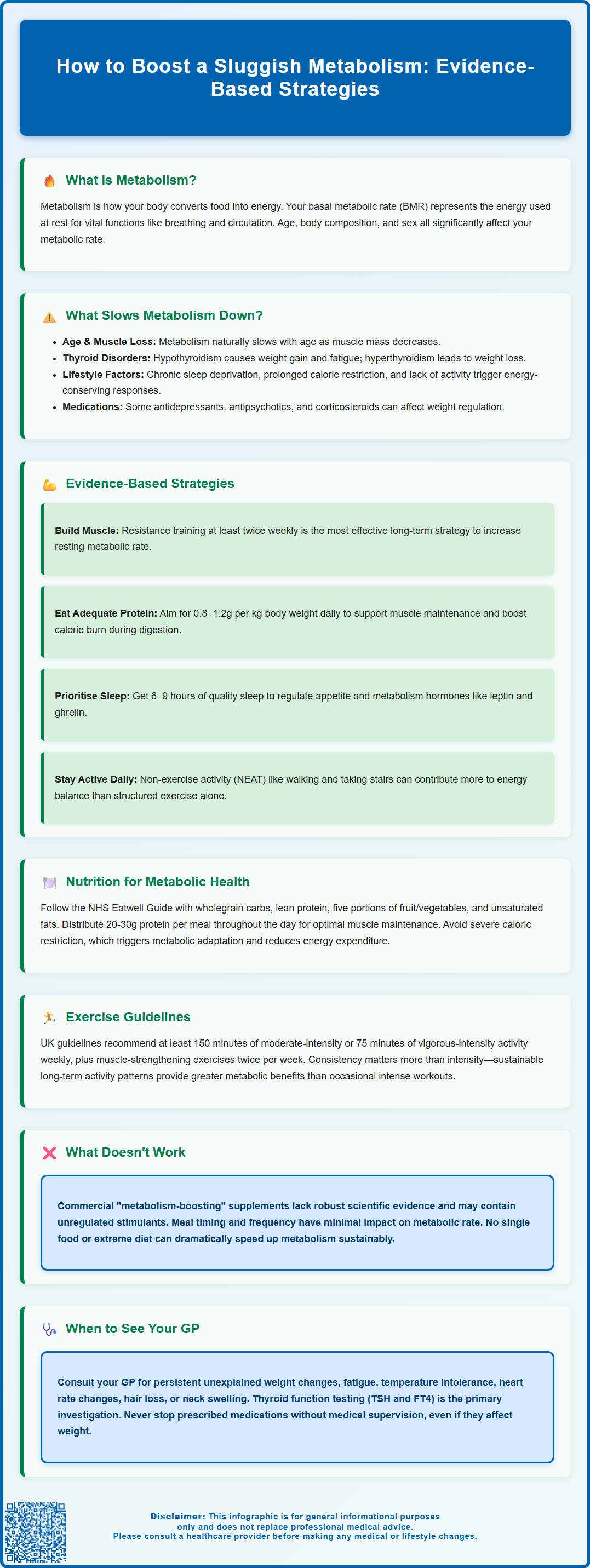

Many people wonder how to boost a sluggish metabolism when facing unexplained weight changes or persistent fatigue. Whilst true metabolic disorders are uncommon, several evidence-based strategies can support optimal metabolic function. Your metabolic rate—the energy your body uses at rest—is influenced by factors including age, body composition, genetics, and hormonal health. Understanding these mechanisms helps distinguish between normal metabolic variation and conditions requiring medical attention. This article examines the science behind metabolism, explores practical interventions supported by UK clinical guidance, and clarifies when professional assessment is warranted.

Summary: Supporting a sluggish metabolism involves resistance training to build muscle mass, adequate protein intake, quality sleep, and avoiding severe caloric restriction, though true metabolic disorders require medical evaluation.

- Basal metabolic rate is influenced by age, body composition, sex, genetics, and hormonal conditions such as thyroid disorders.

- Resistance training increases lean muscle mass, which elevates resting metabolic rate more effectively than aerobic exercise alone.

- Protein has a higher thermic effect (20–30% of calories consumed) compared to carbohydrates (5–10%) or fats (0–3%).

- Chronic sleep deprivation disrupts appetite-regulating hormones including leptin and ghrelin, affecting metabolic function.

- Hypothyroidism requires medical diagnosis through thyroid function testing (TSH and FT4) and treatment with levothyroxine when indicated.

- Seek GP assessment for unexplained weight changes, persistent fatigue, temperature intolerance, or other symptoms suggesting thyroid dysfunction.

Table of Contents

What Is a Sluggish Metabolism and What Causes It?

Metabolism refers to the complex biochemical processes by which your body converts food and drink into energy. Your basal metabolic rate (BMR) represents the energy expended at rest to maintain vital functions such as breathing, circulation, and cellular repair. A 'sluggish metabolism' is a colloquial term often used to describe a lower-than-expected metabolic rate, though it is important to note that true metabolic disorders are relatively uncommon.

Several factors influence metabolic rate, many of which are beyond immediate control. Age is a significant determinant—metabolic rate typically declines gradually with age, primarily due to changes in body composition and loss of lean muscle mass. Body composition plays a crucial role, as muscle tissue is metabolically more active than adipose (fat) tissue. Individuals with higher muscle mass generally have higher resting energy expenditure. Sex also matters: men typically have faster metabolic rates than women due to greater muscle mass and lower body fat percentages.

Other contributing factors include genetics, which can account for variations in metabolic rate between individuals, and hormonal conditions. Thyroid disorders can genuinely affect metabolism—hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) may cause unexplained weight gain, fatigue, cold intolerance, and constipation, while hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) can lead to weight loss, heat intolerance, and palpitations. Conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), Cushing's syndrome, and certain medications (including some antidepressants, antipsychotics, and corticosteroids) may affect weight regulation and energy balance, often through effects on appetite and insulin sensitivity.

Lifestyle factors such as chronic sleep deprivation, prolonged caloric restriction, and sedentary behaviour can influence energy balance through adaptive thermogenesis—the body's protective response to conserve energy. Understanding these mechanisms is essential before considering interventions to support metabolic health.

Evidence-Based Ways to Support Your Metabolic Rate

Whilst you cannot dramatically alter your baseline metabolic rate, evidence supports several strategies to optimise metabolic function within physiological limits. It is crucial to approach claims about 'boosting metabolism' with appropriate scepticism, as many commercial products lack robust scientific support.

Resistance training and muscle preservation represent the most effective long-term approach. Muscle tissue requires more energy to maintain than fat tissue, so increasing lean body mass through progressive resistance exercise can modestly elevate resting metabolic rate. Regular strength training may contribute to small increases in metabolic rate primarily through gains in lean mass. The UK Chief Medical Officers recommend muscle-strengthening activities on at least two days per week for adults.

Adequate protein intake supports muscle maintenance and has a higher thermic effect of food (TEF) compared to carbohydrates or fats. Protein digestion and metabolism require approximately 20–30% of the calories consumed, compared to 5–10% for carbohydrates and 0–3% for fats. For most adults, protein needs range from 0.8–1.2g per kg of body weight daily, with higher amounts sometimes beneficial for older adults or those who are very active. People with kidney disease should consult their healthcare provider before significantly increasing protein intake.

Avoiding severe caloric restriction is important, as prolonged very-low-calorie diets can trigger metabolic adaptation, potentially reducing energy expenditure beyond what would be expected from weight loss alone. This phenomenon, sometimes called 'adaptive thermogenesis', represents the body's survival mechanism.

Optimising sleep quality matters significantly. Research indicates that chronic sleep deprivation disrupts hormones regulating appetite and metabolism, including leptin and ghrelin. The NHS recommends 6–9 hours of quality sleep for most adults.

There is no official link between specific 'metabolism-boosting' supplements and sustained increases in metabolic rate, despite widespread marketing claims. Some supplements contain stimulants that may pose health risks, and many products lack proper regulation in the UK.

The Role of Diet and Nutrition in Metabolism

Nutrition profoundly influences metabolic function, though no single food or dietary pattern can dramatically 'speed up' metabolism. Understanding the thermic effect of food (TEF)—the energy required to digest, absorb, and process nutrients—provides insight into how different macronutrients affect energy expenditure.

A balanced, nutrient-dense diet supports optimal metabolic function. The NHS Eatwell Guide recommends:

-

Base meals on wholegrain starchy carbohydrates (providing sustained energy)

-

Include lean protein sources at each meal (supporting muscle maintenance)

-

Consume at least five portions of varied fruit and vegetables daily (providing essential micronutrients)

-

Choose unsaturated fats in small amounts (supporting hormone production)

-

Stay adequately hydrated with 6–8 glasses of fluid daily

Protein distribution throughout the day may support muscle protein synthesis more effectively than consuming large amounts in a single meal. Aim for approximately 20–30g of protein per meal, adjusted to individual requirements based on body weight and activity level.

Micronutrient deficiencies can impair metabolic function. Iron deficiency affects oxygen transport to tissues, potentially reducing energy expenditure. Iodine is essential for thyroid hormone synthesis, and deficiency can contribute to hypothyroidism. Focus on dietary sources of iodine (such as fish, dairy and eggs) rather than supplements, as excessive iodine from supplements can disrupt thyroid function. Vitamin D, B vitamins, and magnesium all play roles in energy metabolism, though supplementation beyond correcting deficiency offers no proven metabolic advantage.

Meal timing and frequency have minimal impact on metabolic rate. The notion that eating small, frequent meals 'stokes the metabolic fire' is not supported by robust evidence. Total daily energy intake and macronutrient composition matter more than meal frequency. Some individuals find that regular meal patterns help regulate appetite and energy levels, whilst others prefer fewer, larger meals—both approaches can support metabolic health when total nutrition is adequate.

Extreme dietary approaches, including prolonged fasting or very-low-carbohydrate diets, may initially cause water weight loss but do not sustainably increase metabolic rate.

How Physical Activity Affects Metabolic Function

Physical activity influences metabolism through multiple mechanisms, extending beyond the immediate calories burned during exercise. Understanding these pathways helps inform realistic expectations about activity's role in metabolic health.

Aerobic exercise (such as brisk walking, cycling, or swimming) increases energy expenditure during the activity itself and for a brief period afterwards through excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC). Whilst moderate-intensity aerobic exercise produces modest EPOC lasting 1–2 hours, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) may extend this effect, though the total additional calories burned remain relatively small and vary considerably between individuals.

The UK Chief Medical Officers recommend that adults achieve:

-

At least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity weekly

-

Muscle-strengthening activities involving all major muscle groups on at least two days per week

-

Minimising sedentary time where possible

Resistance training provides the most significant long-term metabolic benefit by increasing lean muscle mass. Each kilogram of muscle tissue burns more calories at rest than fat tissue. Whilst this difference may seem modest, the cumulative effect over time, combined with improved insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, makes resistance training a cornerstone of metabolic health.

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT)—the energy expended through daily activities like walking, standing, and fidgeting—can account for a significant portion of total daily energy expenditure in active individuals. Increasing NEAT through simple lifestyle modifications (taking stairs, standing whilst working, active commuting) may contribute more to long-term energy balance than structured exercise alone.

Exercise intensity and duration both matter, but consistency proves most important. A sustainable activity pattern that you can maintain long-term will benefit metabolic health more than sporadic intense efforts. For individuals with existing health conditions, consultation with a healthcare professional before beginning a new exercise programme is advisable.

When to Seek Medical Advice About Your Metabolism

Whilst many people attribute weight changes or fatigue to a 'slow metabolism', genuine metabolic disorders require medical evaluation and management. Recognising when symptoms warrant professional assessment is crucial for timely diagnosis and treatment.

Contact your GP if you experience:

-

Persistent, unexplained weight change (either gain or loss) despite no changes in diet or activity

-

Persistent, unexplained fatigue that interferes with daily activities

-

Cold intolerance or heat intolerance

-

Significant changes in heart rate (either unusually slow or rapid)

-

Constipation, dry skin, hair loss, or muscle weakness

-

Tremor, anxiety, or palpitations

-

Difficulty concentrating or memory problems

-

Changes in menstrual patterns (in women of reproductive age)

-

A lump or swelling in your neck, or changes to your voice

Seek urgent medical attention if you experience severe palpitations, chest pain, or breathlessness.

Thyroid function testing is the primary investigation for suspected metabolic disorders. Your GP will typically measure thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) with reflex free thyroxine (FT4) if TSH is abnormal. According to NICE guidance, hypothyroidism is diagnosed when TSH is elevated above the reference range, usually with low FT4. Treatment with levothyroxine is typically recommended when TSH is ≥10 mIU/L or in certain circumstances such as pregnancy. Thyroid management requires special consideration during pregnancy.

Other investigations may include:

-

Full blood count (checking for anaemia)

-

Fasting glucose and HbA1c (assessing diabetes risk)

-

Lipid profile

-

Vitamin D, B12, and folate levels

-

Specific tests for Cushing's syndrome if suspected (such as overnight dexamethasone suppression test or late-night salivary cortisol)

Medication review is important, as certain prescribed drugs can affect weight and metabolism. Never discontinue prescribed medication without medical supervision, but discuss concerns with your GP, who may consider alternatives if appropriate.

If you have struggled with weight management despite sustained lifestyle modifications, your GP may refer you to specialist services. NHS weight management programmes, dietetic services, or endocrinology referral may be appropriate depending on individual circumstances. Remember that sustainable metabolic health results from consistent, evidence-based lifestyle practices rather than quick fixes or unproven supplements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you actually speed up a slow metabolism?

You cannot dramatically alter your baseline metabolic rate, but resistance training to build muscle mass, adequate protein intake, quality sleep, and avoiding severe caloric restriction can optimise metabolic function within physiological limits.

What medical conditions cause a genuinely slow metabolism?

Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) is the most common condition affecting metabolism, causing unexplained weight gain, fatigue, and cold intolerance. Other conditions include Cushing's syndrome and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which require medical diagnosis and management.

When should I see my GP about metabolism concerns?

Contact your GP if you experience persistent unexplained weight changes, ongoing fatigue interfering with daily activities, temperature intolerance, significant heart rate changes, or other symptoms such as hair loss, constipation, or neck swelling that may indicate thyroid dysfunction.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript