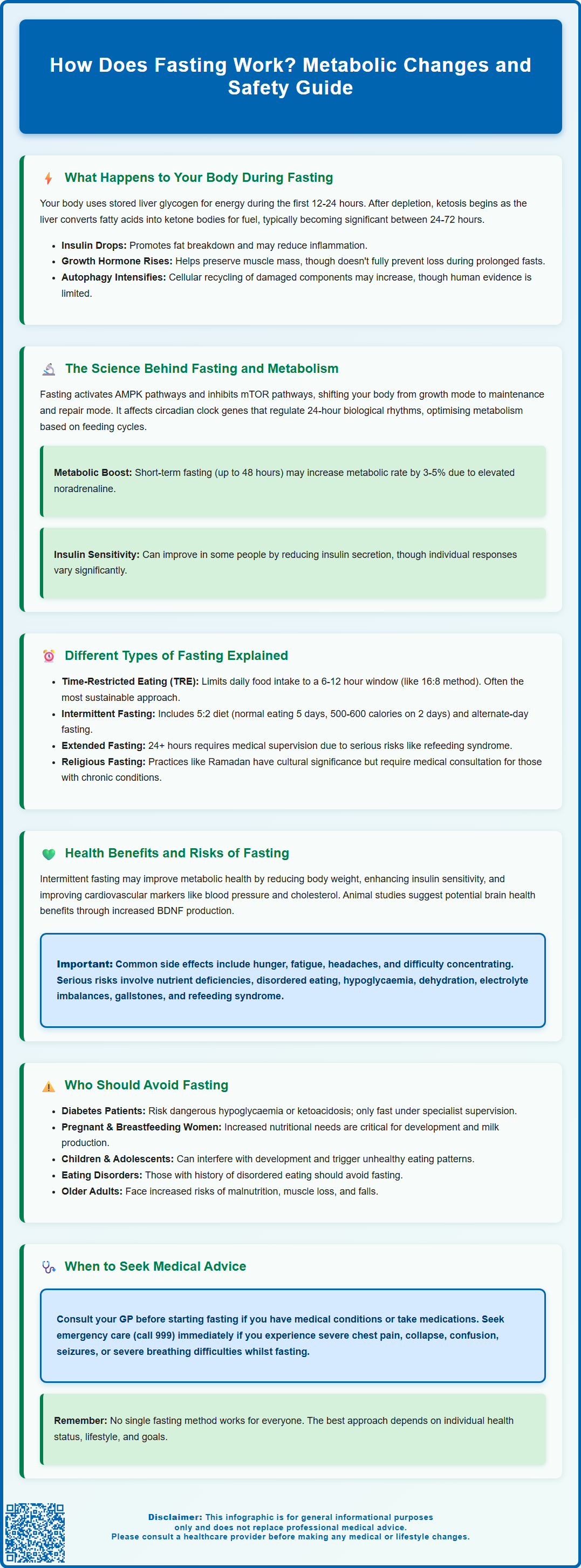

How does fasting work? Fasting initiates a series of metabolic adaptations that fundamentally alter how your body produces and uses energy. Within hours of your last meal, your body shifts from using glucose as its primary fuel source to breaking down stored fat for energy, a process that triggers hormonal changes and activates cellular repair mechanisms. Whilst fasting has been practised for centuries for religious and cultural reasons, modern research is uncovering the biochemical pathways that underpin its effects on metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and cellular function. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for anyone considering fasting as part of their health strategy, particularly given the important safety considerations and individual variations in response.

Summary: Fasting works by depleting glucose stores within 12–24 hours, prompting the body to break down fat into ketones for energy whilst triggering hormonal changes and cellular repair processes.

- Glycogen reserves are exhausted after 12–24 hours, after which the liver converts fatty acids into ketone bodies for fuel.

- Insulin levels drop during fasting, facilitating fat breakdown and potentially improving insulin sensitivity in some individuals.

- Fasting activates cellular repair mechanisms such as autophagy, though direct human evidence remains limited.

- Common side effects include hunger, fatigue, and headaches; serious risks include hypoglycaemia, electrolyte imbalances, and refeeding syndrome.

- People with diabetes, pregnant or breastfeeding women, children, and those with eating disorders should avoid fasting or seek specialist supervision.

- Medical consultation is essential before starting any fasting regimen, particularly for individuals with chronic conditions or taking regular medications.

Table of Contents

What Happens to Your Body During Fasting

Fasting triggers a cascade of metabolic adaptations that begin within hours of your last meal. Initially, your body relies on glucose stored in the liver as glycogen to maintain blood sugar levels and provide energy to cells. These glycogen reserves typically last between 12 to 24 hours, depending on your activity level and metabolic rate.

As glycogen stores become depleted, your body gradually transitions toward ketosis. During this phase, the liver begins breaking down fatty acids into ketone bodies, which serve as an alternative fuel source for the brain and other tissues. Ketones typically begin to rise after 12-24 hours, though significant nutritional ketosis often develops between 24-72 hours, with considerable individual variation based on factors such as body composition, physical activity, and prior dietary habits.

As fasting continues, several hormonal changes occur. Insulin levels drop significantly, which facilitates fat breakdown and may affect certain inflammatory markers. Human growth hormone (HGH) levels may increase, which helps preserve lean tissue, though this effect is variable and may not prevent muscle loss during prolonged fasting. Noradrenaline levels also rise, enhancing alertness and metabolic rate.

Cellular repair processes may become more active during extended fasting periods. Autophagy, a process where cells break down and recycle damaged components, is thought to intensify during fasting, though direct evidence in humans remains limited. These physiological changes represent your body's adaptation to periods without food, a survival mechanism refined over millennia of human evolution.

The Science Behind Fasting and Metabolism

The metabolic effects of fasting are mediated through complex biochemical pathways that influence energy production, hormone regulation, and cellular function. At the molecular level, fasting activates specific signalling pathways, most notably the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway and the inhibition of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. AMPK acts as a cellular energy sensor, promoting catabolic processes that generate energy, whilst mTOR inhibition reduces cell growth and protein synthesis, redirecting resources towards maintenance and repair.

Insulin sensitivity may improve during fasting periods for some individuals. When you eat, insulin is released to facilitate glucose uptake into cells. During fasting, reduced insulin secretion allows cells to become more responsive to insulin when food is reintroduced. This effect on insulin sensitivity varies considerably between individuals and depends on the specific fasting protocol. Research published in peer-reviewed journals suggests that intermittent fasting may improve markers of insulin resistance in some people, though responses are heterogeneous.

Fasting also influences circadian rhythm regulation and gene expression. Studies have identified that fasting affects the expression of genes involved in metabolism, stress resistance, and longevity. The circadian clock genes, which regulate the body's 24-hour biological rhythms, interact with metabolic pathways to optimise energy utilisation based on feeding and fasting cycles. Disruption of these rhythms through irregular eating patterns may contribute to metabolic dysfunction.

The metabolic rate during fasting does not simply decline as commonly believed. Short-term fasting (up to 48 hours) may lead to small increases in metabolic rate (approximately 3-5%) due to elevated noradrenaline levels. However, prolonged fasting beyond several days can lead to metabolic adaptation where the body reduces energy expenditure to conserve resources. This distinction is important when considering different fasting protocols and their metabolic effects.

Different Types of Fasting Explained

Several fasting protocols have gained attention in recent years, each with distinct characteristics and potential applications. Time-restricted eating (TRE) involves limiting food intake to a specific window each day, typically ranging from 6 to 12 hours. The popular 16:8 method, where individuals fast for 16 hours and eat within an 8-hour window, falls into this category. TRE aligns eating patterns with circadian rhythms and may be the most sustainable approach for many people, as it can be incorporated into daily routines with relative ease.

Intermittent fasting (IF) encompasses various patterns, including the 5:2 diet, where individuals eat normally for five days per week and restrict calorie intake to approximately 500-600 calories on two non-consecutive days. Alternate-day fasting (ADF) involves alternating between fasting days (typically consuming about 0-25% of usual energy intake) and regular eating days. These approaches create a caloric deficit whilst potentially offering metabolic benefits beyond simple calorie restriction.

Extended fasting refers to periods of 24 hours or longer without caloric intake, sometimes lasting several days. Water fasting permits only water consumption, whilst modified fasting may allow small amounts of specific nutrients or very low-calorie intake. Extended fasts should only be undertaken with medical supervision due to risks including refeeding syndrome when reintroducing food. Careful monitoring and gradual refeeding are essential, particularly for individuals with underlying health conditions or those taking medications.

Religious and cultural fasting practices, such as Ramadan fasting (dawn-to-sunset abstinence from food and drink) or periodic fasting in various faith traditions, represent time-honoured approaches with specific spiritual and communal significance. People with chronic conditions such as diabetes should seek medical advice before participating in religious fasting to ensure medication adjustments and safety monitoring.

The choice of fasting method should consider individual health status, lifestyle factors, and personal goals. There is no universally superior approach, and what works well for one person may not suit another. Consultation with a healthcare professional is advisable before beginning any structured fasting regimen, particularly for those with pre-existing medical conditions.

Health Benefits and Risks of Fasting

Research into fasting has identified several potential health benefits, though it is important to note that much of the evidence comes from animal studies or small human trials, and long-term effects require further investigation. Metabolic health improvements represent one of the most studied areas. Some evidence suggests that intermittent fasting may help reduce body weight, improve insulin sensitivity, and favourably affect markers of cardiovascular health such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and inflammatory markers. NICE guidance on obesity management (CG189) acknowledges various dietary approaches, though no single approach is recommended as superior to others.

Cardiovascular benefits may include reductions in risk factors for heart disease. Studies have shown that fasting can decrease LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein. However, these effects are often comparable to those achieved through continuous calorie restriction, and there is no official link establishing fasting as superior to other evidence-based dietary interventions for cardiovascular disease prevention.

Cognitive function and neuroprotection have been explored in preliminary research. Animal studies suggest that fasting may enhance brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) production, which supports neuronal health and cognitive function. Some researchers hypothesise that fasting might reduce the risk of neurodegenerative conditions, though robust human evidence is lacking.

However, fasting carries potential risks and adverse effects that warrant careful consideration. Common side effects include hunger, irritability, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, and headaches, particularly during the adaptation period. Some individuals experience dizziness, nausea, or sleep disturbances. More serious concerns include:

-

Nutrient deficiencies if fasting is prolonged or poorly planned

-

Disordered eating patterns or exacerbation of existing eating disorders

-

Hypoglycaemia in individuals with diabetes or those taking certain medications

-

Dehydration, particularly with fasting protocols that restrict fluid intake

-

Electrolyte imbalances during extended fasts

-

Gallstones associated with rapid weight loss

-

Refeeding syndrome when reintroducing food after prolonged fasting

-

Gout flares due to increased uric acid levels during fasting

When to seek medical help: Contact your GP if you experience persistent weakness, worsening symptoms, or concerns during fasting. Call NHS 111 for urgent non-emergency advice. Stop fasting immediately and call 999 if you experience severe chest pain, collapse, confusion, seizures, or severe shortness of breath. If you have a medical condition or take regular medications, consult your healthcare provider before beginning any fasting regimen.

Who Should Avoid Fasting

Certain populations should avoid fasting or only undertake it under close medical supervision due to increased health risks. Individuals with diabetes, particularly those taking insulin or sulphonylureas, face significant risks of hypoglycaemia during fasting. People with type 1 diabetes and those taking SGLT2 inhibitors are at particular risk of developing ketoacidosis (even with normal blood glucose levels) and should generally avoid fasting unless under specialist supervision. If you have diabetes and wish to try fasting, this must be discussed with your diabetes care team, who can adjust medications and provide appropriate monitoring guidance.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women should not fast, as their nutritional requirements are substantially increased to support foetal development or milk production. Fasting during pregnancy may compromise foetal growth and development, whilst fasting during lactation can affect milk supply and maternal nutritional status. Adequate nutrition during these periods is essential for both maternal and infant health.

Children and adolescents require consistent nutrition to support growth, development, and cognitive function. Fasting is generally inappropriate for this age group, as it may interfere with normal development and establish unhealthy relationships with food. Any dietary modifications for young people should be discussed with a paediatrician or registered dietitian.

Individuals with eating disorders or a history of disordered eating should avoid fasting, as it may trigger or exacerbate unhealthy eating patterns, obsessive thoughts about food, or binge-eating episodes. The restrictive nature of fasting can be particularly problematic for those vulnerable to eating disorders. Support is available through organisations such as BEAT (the UK's eating disorder charity).

Other contraindications include:

-

Underweight individuals (BMI <18.5 kg/m²)

-

Those with a history of malnutrition or nutrient deficiencies

-

People with chronic kidney disease or liver disease

-

Individuals taking medications that require food intake

-

Those with a history of fainting or low blood pressure

-

People recovering from surgery or acute illness

-

Individuals with gout or history of gout flares

-

People with adrenal insufficiency

-

Those with significant frailty

Older adults should approach fasting cautiously, as they may be at increased risk of malnutrition, muscle loss (sarcopenia), falls, and medication-related complications. If you fall into any of these categories and are considering fasting, consultation with your GP or a registered dietitian is essential. They can assess your individual circumstances, review your medications, and provide personalised guidance on whether any form of fasting might be appropriate and safe for you. Remember that there are many evidence-based approaches to improving health and managing weight that do not involve fasting.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take for your body to enter ketosis during fasting?

Ketone bodies typically begin to rise after 12–24 hours of fasting, though significant nutritional ketosis often develops between 24–72 hours. Individual variation depends on factors such as body composition, physical activity level, and prior dietary habits.

Does fasting slow down your metabolism?

Short-term fasting (up to 48 hours) may slightly increase metabolic rate by approximately 3–5% due to elevated noradrenaline levels. However, prolonged fasting beyond several days can lead to metabolic adaptation where the body reduces energy expenditure to conserve resources.

Who should not try fasting?

People with diabetes (especially those on insulin), pregnant or breastfeeding women, children and adolescents, individuals with eating disorders, those who are underweight, and people with chronic kidney or liver disease should avoid fasting or only undertake it under close medical supervision.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript