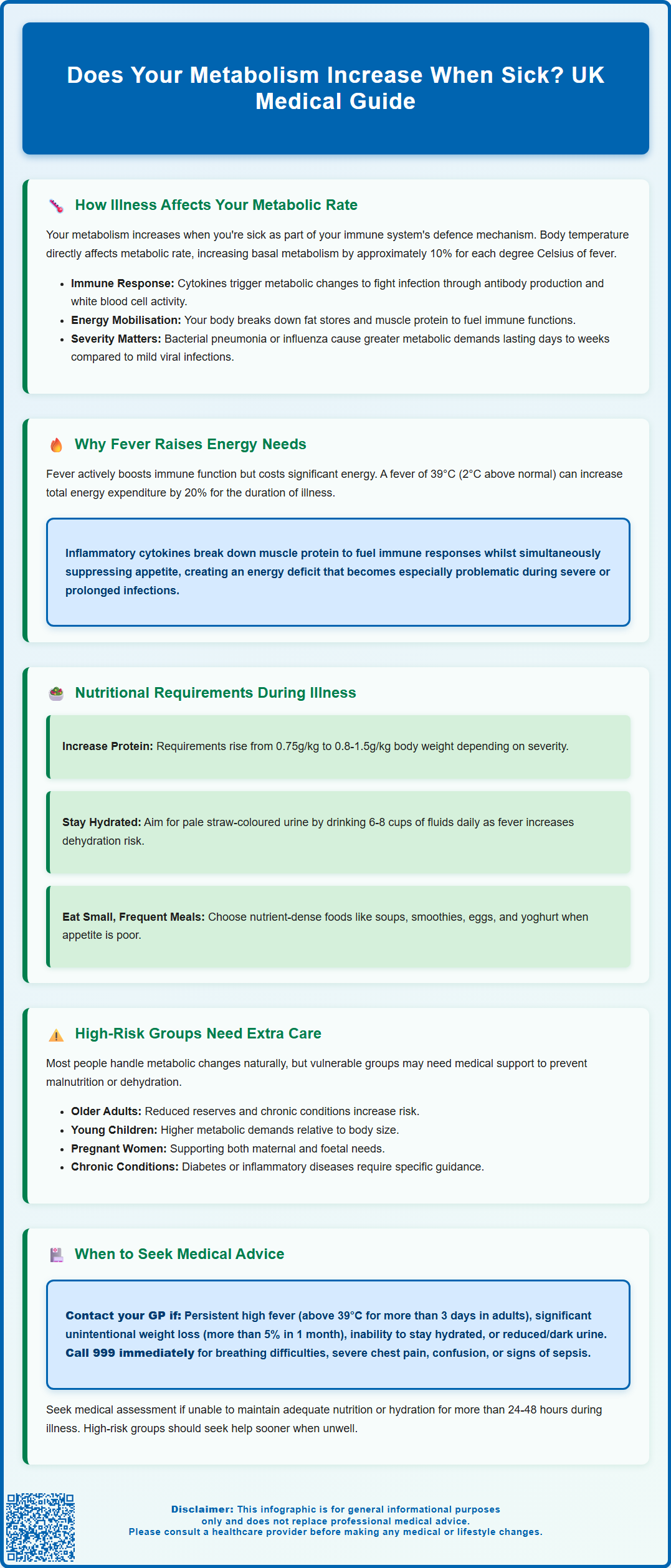

Does your metabolism increase when sick? Yes, your metabolic rate typically rises during illness as part of your body's natural defence mechanism. When you're unwell, your immune system triggers a complex physiological response that demands additional energy to fight infection, produce antibodies, and repair damaged tissues. This metabolic elevation varies depending on the type and severity of illness, with fever being a particularly energy-intensive process. Understanding how illness affects your metabolism helps explain why adequate nutrition and hydration become especially important during recovery, and why certain vulnerable groups may require medical support to manage these increased demands safely.

Summary: Yes, metabolism typically increases during illness, with basal metabolic rate rising approximately 10% for each degree Celsius of fever as the body mobilises energy to support immune function and fight infection.

- Metabolic rate increases during illness through cytokine release, triggering enhanced protein turnover, glucose metabolism, and oxygen consumption to support immune defence.

- Fever elevates energy expenditure by approximately 10% per degree Celsius above normal body temperature (37°C), making it one of the most energy-intensive aspects of illness.

- Nutritional requirements increase during illness, with protein needs potentially rising from 0.75g/kg to 0.8–1.5g/kg depending on severity and individual clinical status.

- Vulnerable groups including older adults, young children, pregnant women, and those with chronic conditions require particular attention to meet increased metabolic demands safely.

- Seek medical advice for persistent high fever (>39°C for >3 days), significant unintentional weight loss (>5% in 1 month), inability to maintain hydration, or worsening symptoms despite treatment.

Table of Contents

Does Your Metabolism Increase When Sick?

Yes, your metabolism typically increases when you're unwell. When the body detects infection or illness, it initiates a complex physiological response that requires additional energy expenditure. This metabolic elevation is part of the immune system's defence mechanism and can vary considerably depending on the type and severity of illness.

The extent of metabolic increase depends on several factors, including the nature of the infection, presence of fever, and overall health status. Research suggests that basal metabolic rate (BMR) can increase by approximately 10% for each degree Celsius rise in body temperature. During severe infections, metabolic rate may increase significantly, while even mild illnesses can elevate energy expenditure, though the exact percentage varies between individuals.

Understanding this metabolic shift is important for several reasons. Firstly, it explains why you may experience increased appetite during recovery or, conversely, why inadequate nutrition during illness can delay healing. Secondly, it highlights the body's remarkable ability to prioritise immune function over other processes. The increased metabolic demand reflects the energy-intensive nature of mounting an effective immune response, including antibody production, white blood cell activity, and tissue repair.

For most people with acute, self-limiting illnesses, the body manages these metabolic changes effectively without intervention. However, in vulnerable populations—including older adults, young children, those with chronic conditions, or individuals with severe infections—the increased metabolic demands may require medical attention and nutritional support to prevent complications such as malnutrition or dehydration.

How Illness Affects Your Metabolic Rate

The metabolic response to illness involves multiple interconnected physiological systems. When pathogens enter the body, the immune system releases signalling molecules called cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). These inflammatory mediators trigger a cascade of metabolic changes designed to support immune function and eliminate the infectious agent.

Key metabolic alterations during illness include:

-

Increased protein turnover – The body breaks down muscle protein to provide amino acids for antibody production and acute-phase protein synthesis in the liver

-

Enhanced glucose metabolism – Immune cells, particularly activated white blood cells, require substantial glucose for energy, leading to increased glucose utilisation

-

Altered fat metabolism – The body mobilises fat stores through increased lipolysis, though insulin resistance may develop during acute illness

-

Elevated oxygen consumption – Increased cellular activity throughout the body raises oxygen demand and carbon dioxide production

The hypothalamus, which regulates body temperature, resets its thermostat to a higher level during infection. This process requires energy to generate and maintain fever through mechanisms such as shivering thermogenesis and increased cellular metabolism. Additionally, the acute-phase response—the body's immediate reaction to infection—demands significant energy for producing defensive proteins like C-reactive protein and fibrinogen.

The severity and duration of metabolic elevation correlate with illness severity. Viral upper respiratory tract infections typically cause modest, short-lived increases, whilst bacterial pneumonia or influenza may produce more substantial metabolic demands lasting several days to weeks. Chronic inflammatory conditions can result in elevated metabolic rates, potentially contributing to unintentional weight loss if nutritional intake doesn't compensate for increased energy expenditure.

Why Fever and Infection Raise Energy Needs

Fever represents one of the most energy-intensive aspects of the illness response. The elevation in body temperature is not merely a side effect of infection but an active, regulated process that enhances immune function. Higher temperatures improve the efficiency of certain immune cells, inhibit pathogen replication, and accelerate biochemical reactions involved in the immune response. However, maintaining this elevated temperature requires substantial energy.

The relationship between fever and metabolism follows a predictable pattern. For every 1°C increase in core body temperature above the normal 37°C, metabolic rate increases by approximately 10%. Therefore, a person with a fever of 39°C (2°C above normal) may experience a 20% increase in energy expenditure. This increased demand persists throughout the febrile period and explains why fever can be particularly taxing, especially in prolonged illnesses.

Beyond fever, infection itself drives metabolic increases through several mechanisms:

-

Immune cell proliferation and activity – White blood cells multiply rapidly and consume significant glucose and amino acids during activation

-

Acute-phase protein synthesis – The liver produces large quantities of defensive proteins, requiring substantial amino acid resources

-

Tissue repair processes – Damaged tissues require energy and building blocks for regeneration

-

Increased cardiovascular work – The heart works harder to deliver oxygen and nutrients to tissues, whilst respiratory rate increases to meet elevated oxygen demands

The cytokines released during infection also directly affect metabolic pathways. IL-1 and TNF-α promote muscle protein breakdown (catabolism) to liberate amino acids for immune function. Simultaneously, these mediators can suppress appetite—a phenomenon known as anorexia of infection—creating a mismatch between increased energy needs and reduced intake. This response can become problematic in severe or prolonged illness, particularly in vulnerable individuals.

Nutritional Requirements During Illness

Meeting increased nutritional demands during illness supports recovery and prevents complications. Whilst appetite often decreases when unwell, maintaining adequate nutrition becomes particularly important given the elevated metabolic rate. The specific nutritional requirements vary depending on illness severity and individual circumstances.

Energy and macronutrient needs typically increase during illness:

-

Kilocalories (kcal) – Energy requirements may increase during illness, with needs typically estimated at 25-35 kcal/kg/day depending on illness severity and individual factors

-

Protein – Protein needs may increase from the standard UK Reference Nutrient Intake of 0.75g per kilogram body weight to 0.8-1.5g/kg in illness, depending on severity and individual clinical status

-

Carbohydrates – Easily digestible carbohydrates provide readily available energy for immune cells and help maintain blood glucose levels

-

Fluids – Fever, increased respiratory rate, and reduced intake elevate dehydration risk. Aim for regular fluid intake to maintain pale straw-coloured urine (typically 6-8 cups daily for most adults, unless advised otherwise by a healthcare professional)

Practical nutritional strategies during illness include:

-

Consuming small, frequent meals if appetite is poor

-

Choosing nutrient-dense foods such as soups, smoothies, eggs, and yoghurt

-

Prioritising protein-rich foods at each meal

-

Maintaining hydration with water, diluted fruit juice, or oral rehydration solutions if needed

-

Following a balanced diet with fruits and vegetables for vitamins and minerals that support immune function

For most people with self-limiting illnesses, these measures suffice. However, certain groups require particular attention: older adults, who may have reduced reserves and blunted thirst responses; young children, who can deteriorate rapidly with inadequate intake; pregnant women, who have baseline increased requirements; and individuals with chronic conditions such as diabetes, where illness can destabilise metabolic control. People with diabetes should follow 'sick day rules' and seek advice from their diabetes team. Those with kidney or heart disease should follow their healthcare professional's guidance regarding fluid and protein intake. If unable to maintain adequate nutrition or hydration for more than 24–48 hours, medical assessment is advisable.

When to Seek Medical Advice About Metabolism Changes

Whilst increased metabolism during illness is normal, certain situations warrant medical evaluation. Most acute infections resolve within days to a couple of weeks, with metabolic rate returning to baseline as recovery progresses. However, complications can arise, particularly in vulnerable individuals or with severe infections.

Seek prompt medical advice if you experience:

-

Persistent high fever – Temperature above 39°C lasting more than three days in adults, or any fever in infants under 3 months (≥38°C) or 3-6 months (≥39°C)

-

Significant unintentional weight loss – Loss of more than 5% body weight over 1 month or 10% over 3-6 months during or following illness

-

Inability to maintain hydration – Reduced urine output, dark urine, dizziness, or confusion suggesting dehydration

-

Worsening symptoms – Deterioration despite initial improvement, or symptoms persisting beyond expected timeframes

-

Breathing difficulties – Shortness of breath, rapid breathing, or chest pain

-

Altered consciousness – Confusion, excessive drowsiness, or difficulty waking

Call 999 immediately for severe symptoms such as:

-

Severe breathing difficulties or gasping for air

-

Severe chest pain

-

Confusion, severe drowsiness or difficulty waking

-

Signs of sepsis (extreme shivering, severe breathlessness, mottled/discoloured skin)

Contact NHS 111 for urgent advice when your GP is unavailable.

Specific populations should have a lower threshold for seeking assessment:

-

Older adults (over 65 years) with any acute illness and reduced oral intake

-

Individuals with diabetes experiencing illness, as infection can destabilise blood glucose control

-

People with chronic conditions such as heart disease, lung disease, or immunosuppression

-

Pregnant women with fever or persistent symptoms

-

Young children showing signs of dehydration or lethargy

NICE guidance emphasises the importance of safety-netting—providing clear advice about warning signs and when to seek further help. If you're concerned about your ability to meet increased nutritional needs during illness, or if recovery seems prolonged, contact your GP. They can assess for complications, provide tailored nutritional advice, or arrange specialist input if needed. In cases of severe illness with marked metabolic disturbance, hospital admission may be necessary for intravenous fluids, nutritional support, and treatment of the underlying infection.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much does fever increase metabolic rate?

For every 1°C increase in body temperature above the normal 37°C, metabolic rate increases by approximately 10%. Therefore, a fever of 39°C (2°C above normal) may result in a 20% increase in energy expenditure throughout the febrile period.

Should I eat more when I'm ill?

Yes, your body requires additional energy and nutrients during illness to support immune function and recovery. Focus on small, frequent meals with nutrient-dense foods, adequate protein (0.8–1.5g/kg depending on severity), and maintain hydration even if appetite is reduced.

When should I seek medical advice about illness and metabolism?

Seek medical advice if you experience persistent high fever (>39°C for >3 days), significant unintentional weight loss (>5% in 1 month), inability to maintain hydration, worsening symptoms, or breathing difficulties. Vulnerable groups including older adults, young children, and those with chronic conditions should have a lower threshold for seeking assessment.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript