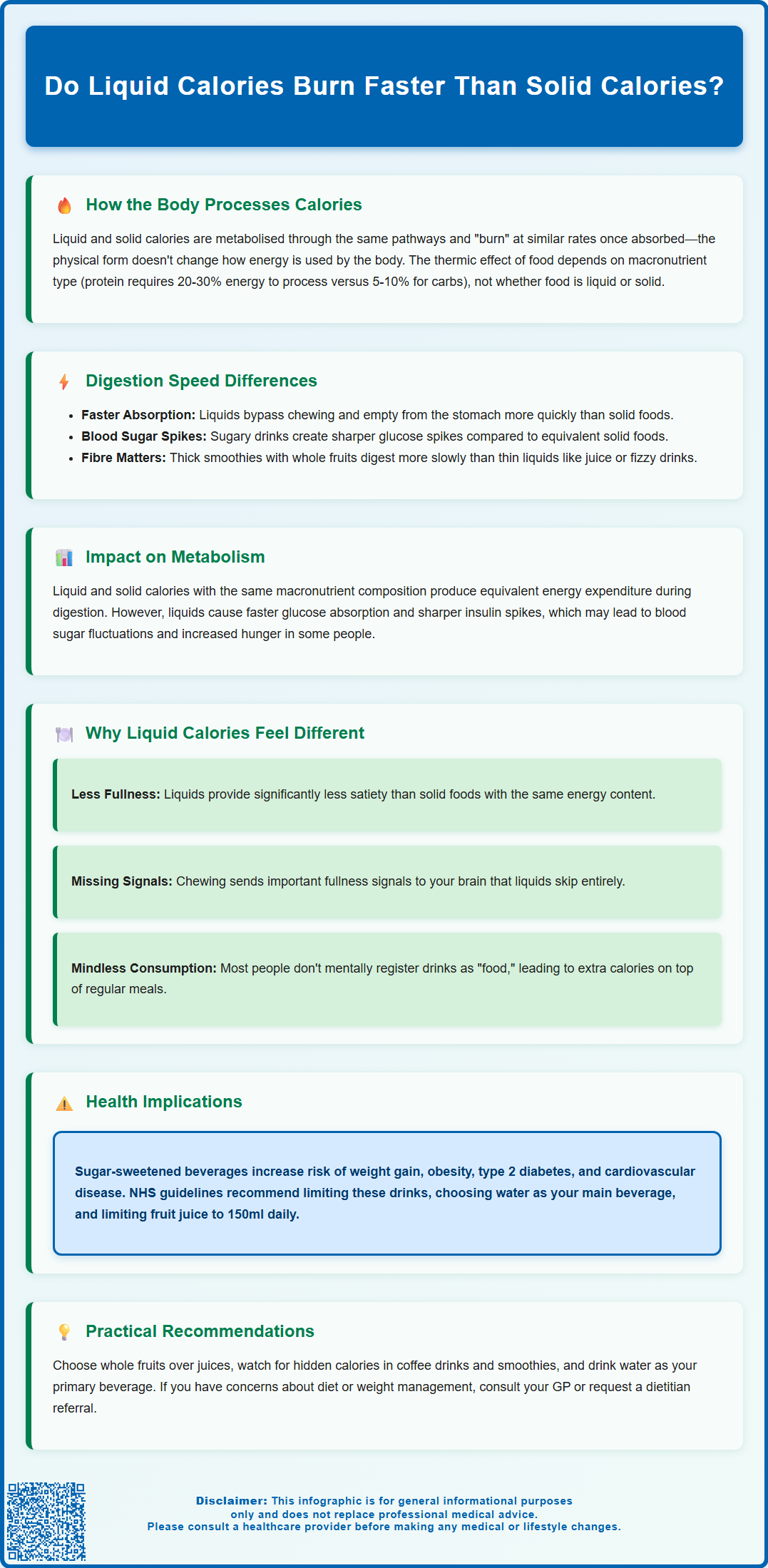

Do liquid calories burn faster than solid calories? This common question reflects confusion about how the body processes different forms of energy. Whilst liquid calories are absorbed more rapidly than solid foods—particularly those high in sugar and low in fibre—they do not 'burn' at different rates once metabolised. The key difference lies in digestion speed and satiety rather than energy expenditure. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for making informed dietary choices, as liquid calories from sugar-sweetened beverages are linked to increased risks of weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Summary: Liquid calories do not burn faster than solid calories; they are absorbed more quickly but metabolised at similar rates once in the bloodstream.

- Liquid calories, especially those high in sugar and low in fibre, empty from the stomach faster than solid foods, leading to quicker nutrient absorption.

- The thermic effect of food (energy cost of digestion) depends on macronutrient composition rather than physical form, with protein generating the highest energy expenditure.

- Liquid calories are significantly less satiating than solid foods, often leading to passive overconsumption and inadequate compensation at subsequent meals.

- High intake of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with increased risk of weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease according to NHS and NICE guidance.

- Consult your GP or request referral to a registered dietitian if concerned about dietary intake, weight management, or blood glucose control.

Table of Contents

Understanding How the Body Processes Liquid vs Solid Calories

The question of whether liquid calories 'burn faster' than solid calories requires clarification of what we mean by 'burning'. In metabolic terms, a calorie is a unit of energy, and the body extracts energy from both liquid and solid foods through digestion and cellular metabolism. The thermic effect of food (TEF)—the energy required to digest, absorb, and process nutrients—varies depending on macronutrient composition rather than the physical state of the food itself.

When we consume calories in liquid form (such as fruit juices, smoothies, or sugar-sweetened beverages), the body processes them through the same fundamental metabolic pathways as solid foods. However, the rate of absorption differs significantly. Liquid calories, particularly those high in sugar and low in fibre, typically require less mechanical breakdown in the stomach and pass more rapidly through the gastrointestinal tract. This accelerated transit means glucose and other nutrients enter the bloodstream more quickly, potentially triggering faster insulin responses.

It is important to distinguish between absorption speed and actual energy expenditure. While liquid calories may be absorbed faster, evidence does not show different oxidation rates solely due to physical form once absorbed. The body's basal metabolic rate and total energy expenditure remain largely determined by factors such as body composition, physical activity, and individual metabolic health rather than whether calories were consumed in liquid or solid form.

The macronutrient profile matters considerably: protein-rich foods (whether liquid or solid) generate higher TEF (approximately 20-30% of calories consumed) compared to carbohydrates (5-10%) or fats (0-3%). Therefore, a protein shake may have a different metabolic impact than a sugar-sweetened beverage, regardless of both being liquids.

Digestion Speed: Liquid Calories Compared to Solid Foods

The digestive process begins in the mouth, where solid foods undergo mechanical breakdown through chewing (mastication) and mixing with salivary enzymes. This initial processing is largely bypassed with liquid calories, which proceed almost immediately to the stomach. Gastric emptying—the rate at which stomach contents move into the small intestine—generally occurs faster with liquids than with solid foods.

Research suggests that thin liquids can empty from the stomach more quickly than solid meals, though the exact timing varies based on numerous factors including meal composition, volume, and individual physiology. This difference has important physiological consequences. The more rapid gastric emptying of liquid calories, especially those high in sugar and low in fibre, means that glucose and other nutrients reach the small intestine more quickly, where absorption into the bloodstream occurs. This can create a sharper postprandial (after-meal) glucose response compared to equivalent solid foods.

The presence of fibre in solid foods further slows digestion. Dietary fibre, particularly soluble fibre, forms a gel-like substance in the digestive tract that delays gastric emptying and slows nutrient absorption. Most processed beverages like soft drinks and fruit juices contain minimal or no fibre, removing this natural 'brake' on digestion.

Viscosity also plays a role: thicker liquids (such as smoothies containing whole fruits and vegetables) may empty from the stomach more slowly than thin liquids (such as fruit juice or fizzy drinks). In some cases, thick, fibre-rich liquid meals may have emptying rates closer to semi-solid foods. The absence of a chewing requirement with liquids may affect the early phases of digestion, though the full impact of this on subsequent metabolic responses requires further research.

Impact on Metabolism and Energy Expenditure

The metabolic fate of calories is determined primarily by their macronutrient composition rather than their physical form. However, the speed of nutrient delivery does influence certain metabolic responses. When liquid calories cause rapid glucose absorption, the pancreas releases insulin quickly to facilitate cellular glucose uptake. These pronounced insulin responses to high-sugar, low-fibre liquids may lead to subsequent blood glucose fluctuations in some individuals, potentially triggering hunger and further food intake.

The thermic effect of food represents the energy cost of digestion, absorption, and nutrient storage. Current evidence suggests minimal difference in total energy expenditure between liquid and solid calories of identical macronutrient composition. A protein shake and a chicken breast of equivalent protein content will generate similar TEF, though the timing of that energy expenditure may differ slightly.

One consideration is that the ease of consuming liquid calories may lead to passive overconsumption. Because liquids require less effort to ingest and digest, individuals may consume larger quantities without the same physical feedback mechanisms that limit solid food intake. This can result in a positive energy balance (consuming more calories than expended), leading to weight gain over time—though this reflects intake rather than differential 'burning' of calories.

For individuals with specific medical conditions, the rapid absorption of liquid calories can be either beneficial or problematic. Patients requiring quick energy replenishment (such as those with certain malabsorption disorders) may benefit from liquid nutritional supplements. Conversely, individuals with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes may experience poorer glycaemic control with liquid calorie consumption. NICE advises limiting sugar-sweetened drinks and adopting a diet with high-fibre, lower-GI carbohydrates as part of diabetes prevention and management.

Satiety and Hunger: Why Liquid Calories Feel Different

One of the most significant differences between liquid and solid calories lies in their effect on satiety—the feeling of fullness that suppresses further eating. Multiple studies have demonstrated that liquid calories are substantially less satiating than solid foods containing equivalent energy and macronutrients. This phenomenon has important implications for appetite regulation and overall energy intake.

Several mechanisms explain reduced satiety from liquid calories:

-

Reduced oro-sensory exposure: Chewing solid food provides sensory feedback that contributes to satiety signalling. The mechanical act of chewing and the extended oral processing time allow the brain to register food intake more effectively.

-

Faster gastric emptying: Because liquids leave the stomach quickly, the physical sensation of stomach fullness (gastric distension) is shorter-lived compared to solid meals.

-

Hormonal responses: Solid foods typically trigger more robust release of satiety hormones such as cholecystokinin (CCK), peptide YY (PYY), and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). These hormones signal fullness to the brain and slow gastric emptying.

-

Lack of fibre: Most liquid calories contain little dietary fibre, which contributes significantly to satiety through gastric distension and delayed nutrient absorption.

Research indicates that people often fail to compensate for liquid calories by reducing subsequent food intake, whereas solid food consumption typically leads to appropriate compensation at later meals. This poor caloric compensation means that liquid calories may be added to rather than substituted for solid food intake, increasing total daily energy consumption.

The psychological perception of beverages as 'drinks' rather than 'food' may also contribute to inadequate satiety responses. Many individuals do not mentally register beverages as contributing substantially to their nutritional intake, leading to mindless consumption alongside regular meals.

Health Implications of Liquid Calorie Consumption

The widespread consumption of liquid calories, particularly sugar-sweetened beverages, has significant public health implications. Evidence consistently links high intake of liquid calories with increased risk of weight gain, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The NHS and NICE recommend limiting consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages as part of healthy eating guidance.

High intake of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with increased risk of metabolic health issues; mechanisms may include excess energy intake and adverse glycaemic effects. NICE guidelines for diabetes prevention emphasise reducing intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and replacing them with water or unsweetened alternatives.

Dental health represents another concern. Liquid sugars bathe the teeth in a cariogenic (cavity-promoting) environment, and acidic beverages can erode tooth enamel. The frequent consumption of sugary or acidic drinks throughout the day provides sustained exposure that solid foods typically do not.

However, not all liquid calories are problematic. Oral nutritional supplements can be valuable for individuals with increased nutritional needs or difficulty consuming adequate solid food, and should be used under the advice of your GP or a registered dietitian. They may benefit:

-

Older adults with reduced appetite or chewing difficulties

-

Patients recovering from surgery or illness

-

Individuals with malabsorption disorders

-

Those requiring additional protein for wound healing

For the general population, practical recommendations include:

-

Prioritising water as the primary beverage

-

Limiting fruit juice to 150ml daily (one small glass), in line with NHS guidance

-

Avoiding regular consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages

-

Choosing whole fruits over fruit juices to retain fibre

-

Being mindful of 'hidden' liquid calories in coffee drinks, smoothies, and alcoholic beverages

If you are concerned about your dietary intake, weight management, or experience symptoms suggestive of blood glucose fluctuations (such as excessive thirst, frequent urination, unusual fatigue, or dizziness after meals), consult your GP or request a referral to a registered dietitian. They can provide personalised advice based on your individual health status and nutritional requirements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are liquid calories worse for weight gain than solid calories?

Liquid calories are less satiating than solid foods, often leading to passive overconsumption without adequate compensation at later meals. This poor caloric compensation means liquid calories may be added to rather than substituted for solid food intake, increasing total daily energy consumption and potentially contributing to weight gain.

Why do liquid calories not fill you up as much as solid food?

Liquid calories provide reduced satiety due to faster gastric emptying, minimal chewing (which reduces oro-sensory feedback), weaker release of satiety hormones like cholecystokinin and peptide YY, and typically lower fibre content. These factors mean the brain registers fullness less effectively with liquids than with solid foods.

Should I avoid all liquid calories for better health?

Not all liquid calories are problematic; oral nutritional supplements can benefit those with increased nutritional needs or difficulty consuming solid food. However, NHS and NICE guidance recommend limiting sugar-sweetened beverages, restricting fruit juice to 150ml daily, and prioritising water as your primary beverage to reduce risks of weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and dental problems.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript