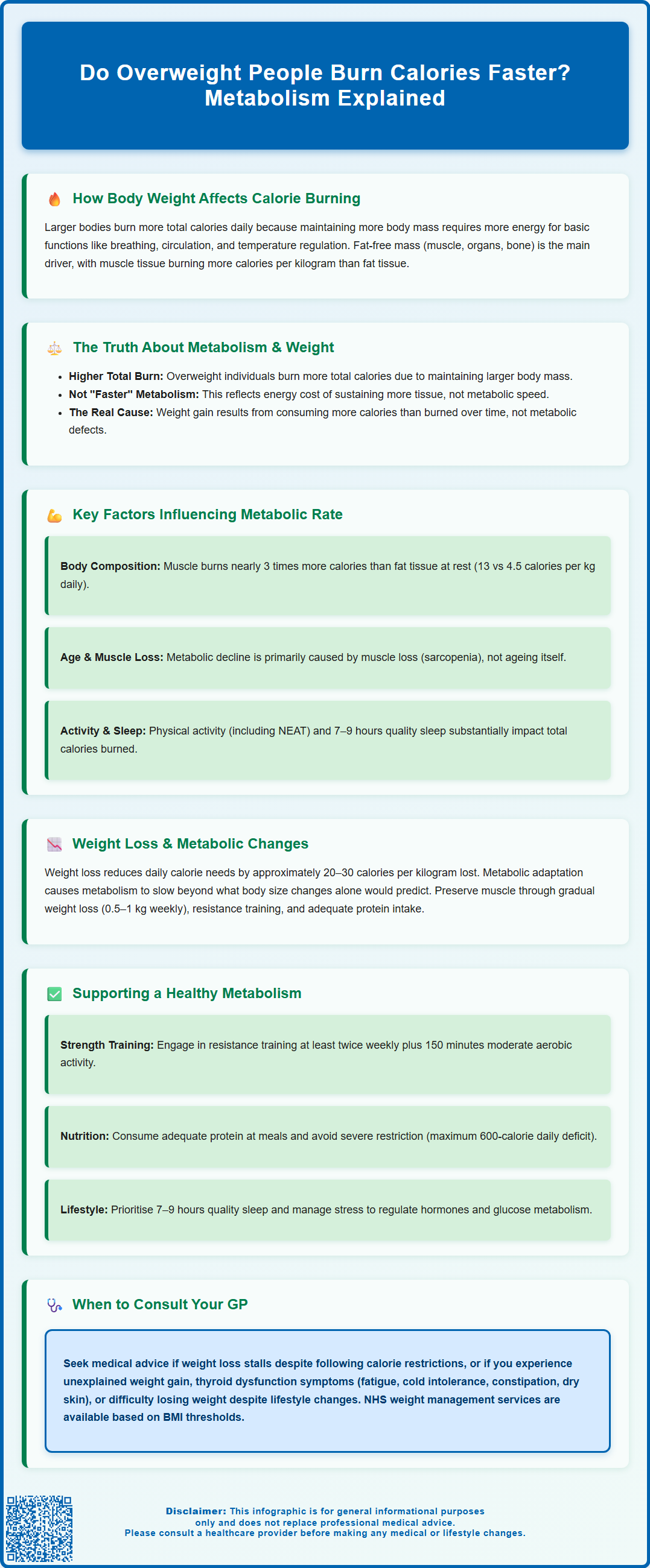

Do overweight people burn calories faster is a common question that reveals important misconceptions about metabolism and body weight. Whilst individuals with higher body weight do burn more total calories daily in absolute terms, this reflects the energy required to maintain a larger body rather than a 'faster' metabolism. Understanding the relationship between body composition, metabolic rate, and energy expenditure is essential for evidence-based weight management. This article examines how body weight affects calorie burning, explores metabolic differences between individuals, and provides practical guidance aligned with UK clinical recommendations for supporting healthy metabolic function.

Summary: Overweight individuals burn more total calories daily in absolute terms due to maintaining a larger body, but this does not indicate a faster metabolism when adjusted for body weight.

- Basal metabolic rate increases with body mass, particularly fat-free mass including muscle, organs, and bone

- Muscle tissue burns approximately 13 calories per kilogram daily at rest, whilst fat tissue burns about 4.5 calories per kilogram

- Weight loss reduces total daily energy expenditure by approximately 20–30 calories per kilogram lost

- Metabolic adaptation following weight loss varies considerably between individuals and may exceed predicted reductions

- Resistance training twice weekly and adequate protein intake help preserve metabolically active muscle tissue during weight management

- Consult your GP for unexplained weight changes or symptoms suggesting thyroid dysfunction or metabolic disorders

Table of Contents

How Body Weight Affects Calorie Burning

Larger bodies require more energy to sustain basic functions. While total body weight matters, fat-free mass (FFM) – including muscle, organs, and bone – is the primary determinant of BMR. A person with greater FFM has more metabolically active tissue to maintain. Muscle tissue burns more calories per kilogram than adipose (fat) tissue, though fat tissue also contributes to energy expenditure through its own metabolic processes.

Total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) comprises three main components: basal metabolic rate (typically 60–75% of total calories burned), the thermic effect of food (approximately 10%, representing energy used to digest and process nutrients), and activity thermogenesis (15–30%, including both structured exercise and non-exercise activity thermogenesis or NEAT). Body composition influences all three components, with the impact most pronounced on BMR.

It is important to distinguish between absolute and relative calorie burning. Whilst a heavier person burns more total calories in absolute terms, when adjusted for body weight (calories per kilogram), the relationship becomes more complex. Understanding this distinction is crucial for interpreting metabolic differences between individuals of varying body compositions and for developing appropriate weight management strategies.

Do Overweight People Burn Calories Faster?

Yes, in absolute terms, overweight and obese individuals typically burn more total calories per day than those with lower body weight, assuming similar activity levels. This increased energy expenditure is primarily due to having greater fat-free mass (FFM) to maintain, though additional fat mass also contributes to energy needs. Research demonstrates that basal metabolic rate increases with body mass, particularly FFM, meaning a person weighing 100 kg will generally have a higher BMR than someone weighing 70 kg.

However, this does not mean overweight individuals have a 'faster' metabolism in the conventional sense. The increased calorie burning is simply a reflection of maintaining a larger body. When metabolic rate is expressed relative to body weight (per kilogram), differences often diminish or reverse. Additionally, body composition matters significantly: two individuals of the same weight may have vastly different metabolic rates depending on their ratio of muscle to fat tissue.

The concept of metabolic efficiency also warrants consideration. Some research suggests that individuals with obesity may experience metabolic adaptations that affect how efficiently they utilise energy, though findings remain mixed. This phenomenon, sometimes called adaptive thermogenesis, varies considerably between individuals. Factors such as insulin resistance, inflammation, and hormonal changes associated with excess adiposity can influence metabolic function in complex ways.

It is a common misconception that people with obesity have inherently 'slow' metabolisms causing their weight gain. Whilst metabolic differences between individuals do exist, they typically account for relatively modest variations in daily energy expenditure. The primary driver of weight gain remains an energy imbalance where caloric intake exceeds expenditure over time. Understanding this helps dispel myths and supports evidence-based approaches to weight management.

Factors That Influence Metabolic Rate

Metabolic rate varies considerably between individuals due to multiple interacting factors, both modifiable and non-modifiable. Body composition is perhaps the most significant determinant: muscle tissue is metabolically active, burning approximately 13 calories per kilogram per day at rest, whilst fat tissue burns only about 4.5 calories per kilogram daily. This explains why individuals with greater muscle mass typically have higher metabolic rates, even at the same total body weight.

Age impacts metabolism, though recent research suggests that after accounting for changes in body composition, metabolic rate remains relatively stable from early adulthood until around age 60. The observed decline in metabolism with age is largely attributable to progressive loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) rather than ageing itself. Sex also plays a role, as men generally have higher metabolic rates than women of similar weight, largely attributable to greater muscle mass and lower body fat percentages on average.

Genetic factors contribute to metabolic variation, with studies suggesting heritability influences differences between individuals. However, genetics interact with environmental and behavioural factors, meaning genetic predisposition does not determine metabolic destiny. Hormonal status affects metabolism: thyroid hormones regulate metabolic rate, with conditions such as hypothyroidism potentially reducing energy expenditure, though the extent varies with severity. Other hormones including cortisol, growth hormone, and sex hormones also influence energy expenditure.

Environmental temperature affects metabolic rate through thermogenesis, as the body expends energy maintaining core temperature. Previous dieting history may influence metabolism through adaptive thermogenesis, where the body reduces energy expenditure in response to caloric restriction. Physical activity levels, including both structured exercise and spontaneous movement (NEAT), substantially impact total daily energy expenditure, with highly active individuals burning significantly more calories than sedentary counterparts. Sleep quality and duration also affect metabolic function, with sleep deprivation associated with altered appetite-regulating hormones and impaired glucose metabolism.

Weight Loss and Changes in Calorie Burning

Weight loss inevitably results in reduced total daily energy expenditure, a physiological reality that presents challenges for long-term weight maintenance. As body mass decreases, fewer calories are required to maintain basic functions, physical activity, and food processing. Research indicates that for every kilogram of weight lost, total daily energy expenditure typically decreases by approximately 20–30 calories per day, though individual variation exists.

Metabolic adaptation, sometimes termed 'adaptive thermogenesis', describes a phenomenon where metabolic rate decreases beyond what would be predicted by changes in body mass and composition alone. Some studies have documented metabolic suppression following significant weight loss, though the extent and duration vary considerably between individuals. This adaptation appears to be the body's protective mechanism against perceived energy deficit, though research continues to investigate its clinical significance.

The composition of weight loss matters considerably. Preserving muscle mass during weight reduction is crucial for maintaining metabolic rate. Rapid weight loss, very low-calorie diets, and inadequate protein intake promote greater muscle loss alongside fat loss, resulting in more pronounced metabolic decline. NICE guidance (CG189) on obesity management emphasises gradual weight loss (0.5–1 kg per week) combined with physical activity to preserve lean tissue.

Strategies to mitigate metabolic adaptation include incorporating resistance training to maintain or build muscle mass, ensuring adequate protein intake (though individuals with kidney disease should seek medical advice before increasing protein), avoiding excessively restrictive diets, and maintaining regular physical activity. Individuals experiencing unexplained difficulty losing weight despite adherence to caloric restriction should consult their GP, as underlying conditions such as hypothyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome, or medication effects may require investigation.

Supporting a Healthy Metabolism

Maintaining optimal metabolic function requires a multifaceted approach addressing nutrition, physical activity, sleep, and overall lifestyle factors. Resistance training is particularly effective for preserving and building metabolically active muscle tissue. The UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines recommend adults engage in muscle-strengthening activities involving all major muscle groups at least twice weekly, alongside at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity weekly.

Adequate protein intake supports muscle maintenance and has a higher thermic effect than carbohydrates or fats, meaning more energy is expended digesting protein. Including protein-rich foods at meals may help optimise muscle protein synthesis. Avoiding severe caloric restriction prevents excessive metabolic adaptation; NICE typically advises a deficit of around 600 calories daily for sustainable weight loss whilst minimising metabolic suppression.

Sleep quality significantly impacts metabolic health. Adults should aim for 7–9 hours of quality sleep nightly, as sleep deprivation disrupts appetite-regulating hormones (increasing ghrelin and decreasing leptin) and impairs glucose metabolism. Stress management is equally important, as chronic stress elevates cortisol, which can promote fat accumulation and insulin resistance.

Staying adequately hydrated supports metabolic processes, though the effect of cold water on energy expenditure is minimal and not a recommended weight management strategy. Regular meal timing may help regulate metabolic function, though evidence remains mixed regarding specific meal frequency recommendations.

When to seek medical advice: Individuals should consult their GP if experiencing unexplained weight gain despite lifestyle modifications, symptoms suggesting thyroid dysfunction (fatigue, cold intolerance, constipation, dry skin), or difficulty losing weight with appropriate interventions. Blood tests can assess thyroid function, glucose metabolism, and other factors affecting metabolic health. Access to weight management services varies by locality in the NHS; generally, lifestyle services may be available for those with BMI ≥30 kg/m² (or ≥27.5 kg/m² for certain ethnic groups), while specialist services (Tier 3) typically require BMI ≥35 kg/m² with complications or ≥40 kg/m². Your GP can advise on local referral pathways.

Scientific References

- Overweight and obesity management.

- Obesity - Treatment.

- Relative changes in resting energy expenditure during weight loss: a systematic review.

- Health matters: physical activity - prevention and management of long-term conditions.

- Skeletal muscle carnitine loading increases energy expenditure, modulates fuel metabolism gene networks and prevents body fat accumulation in humans.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does having a higher body weight mean you have a faster metabolism?

Not necessarily. Whilst individuals with higher body weight burn more total calories daily, this reflects the energy needed to maintain a larger body rather than a metabolically 'faster' system. When adjusted per kilogram of body weight, metabolic differences often diminish or reverse.

Why does metabolism slow down during weight loss?

As body mass decreases, fewer calories are required for basic functions and activity. Additionally, metabolic adaptation may occur where the body reduces energy expenditure beyond predicted levels as a protective mechanism against perceived energy deficit.

How can I support my metabolism during weight management?

Incorporate resistance training at least twice weekly to preserve muscle mass, ensure adequate protein intake, avoid severe caloric restriction, maintain 7–9 hours of quality sleep, and follow a gradual weight loss approach of 0.5–1 kg per week as recommended by NICE guidance.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript