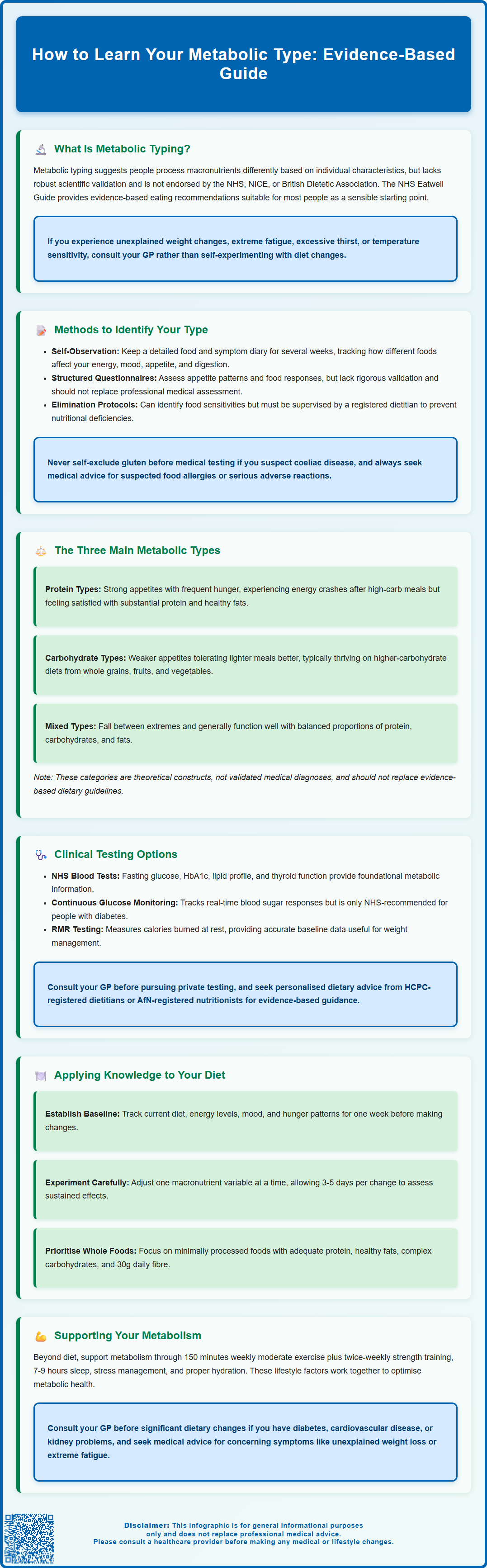

How to learn your metabolic type involves understanding how your body processes carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Metabolic typing is a nutritional concept suggesting individuals respond differently to macronutrients based on unique metabolic characteristics. Whilst the framework lacks robust clinical validation and is not used in NHS care, the principle of personalised nutrition has merit. This article explores methods to identify potential metabolic patterns, the three main metabolic categories, clinical testing options, and practical dietary applications. It's important to note that metabolic typing should complement, not replace, evidence-based medical guidance. If you experience unexplained weight changes, extreme fatigue, or other metabolic symptoms, consult your GP for proper assessment.

Summary: Learning your metabolic type involves self-observation through food diaries, structured questionnaires assessing appetite and energy patterns, and optionally clinical tests, though metabolic typing lacks robust scientific validation and is not used in NHS care.

- Metabolic typing categorises individuals into protein, carbohydrate, or mixed types based on how they process macronutrients, but these classifications are not clinically validated.

- Self-assessment methods include monitoring energy levels, appetite patterns, and responses to different foods over several weeks using detailed food diaries.

- NHS blood tests (fasting glucose, HbA1c, lipid profile, thyroid function) can identify genuine metabolic conditions affecting metabolism, available through your GP.

- The NHS Eatwell Guide provides evidence-based dietary recommendations suitable for most people, and significant dietary changes should be discussed with healthcare professionals.

- Consult your GP if you experience unexplained weight changes, extreme fatigue, excessive thirst, or temperature sensitivity rather than attempting dietary self-experimentation.

Table of Contents

What Is Metabolic Typing and How Does It Work?

Metabolic typing is a nutritional concept that proposes individuals process macronutrients—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—differently based on their unique metabolic characteristics. Proponents suggest that understanding your metabolic type can help optimise dietary choices, energy levels, and overall wellbeing. The theory emerged from observations that people respond differently to the same foods, with some thriving on high-carbohydrate diets whilst others perform better with higher protein or fat intake.

The underlying premise centres on theories about the autonomic nervous system, oxidation rate (how quickly cells convert food to energy), and endocrine gland function. It's important to understand that these frameworks are not clinically validated constructs and are not used in NHS care. There are no validated clinical tests for 'oxidation rate' or autonomic dominance in this context.

Metabolic typing lacks robust scientific validation through large-scale clinical trials. Whilst individual metabolic variation is well-established in medical science—evidenced by conditions such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, and inherited metabolic diseases—the specific categorisation systems used in metabolic typing have not been endorsed by major UK health bodies including NICE, the NHS, or the British Dietetic Association. The concept should be viewed as a complementary approach rather than evidence-based medical guidance.

If you experience symptoms suggestive of metabolic or endocrine disorders (such as unexplained weight changes, extreme fatigue, excessive thirst, or temperature sensitivity), consult your GP rather than attempting dietary self-experimentation. The NHS Eatwell Guide provides evidence-based healthy eating recommendations that serve as a sensible starting point for most people.

That said, the principle of personalised nutrition has merit. Research increasingly supports the idea that genetic factors, gut microbiome composition, and metabolic health influence dietary responses. Understanding your body's signals and working with healthcare professionals to tailor nutritional approaches remains a sensible strategy for optimising health, even if the specific metabolic typing framework requires further scientific substantiation.

Methods to Identify Your Metabolic Type

Several approaches exist for determining your potential metabolic type, ranging from self-assessment questionnaires to more formal testing protocols. Self-observation represents the most accessible starting point. This involves monitoring how different foods affect your energy levels, mood, appetite, and physical sensations over several weeks. Keep a detailed food and symptom diary, noting whether high-carbohydrate meals leave you energised or fatigued, and whether protein-rich foods improve concentration or cause digestive discomfort.

Many metabolic typing systems utilise structured questionnaires that assess various factors including:

-

Your typical appetite patterns and food cravings

-

Energy fluctuations throughout the day

-

Responses to different macronutrient ratios

-

Personality traits and stress responses

-

Physical characteristics such as body temperature regulation

-

Digestive symptoms after specific foods

These questionnaires typically categorise responses to suggest a predominant metabolic profile. However, their validity has not been rigorously tested in peer-reviewed research, and results should be interpreted cautiously. It's important to understand that these are not diagnostic tools and should not replace clinical assessment by healthcare professionals.

Elimination and reintroduction protocols offer another method, but should be approached with caution. These involve temporarily removing certain food groups and systematically reintroducing them whilst monitoring symptoms. Such approaches should ideally be conducted under the supervision of a registered dietitian (RD) to prevent nutritional deficiencies and avoid triggering disordered eating patterns. Importantly, if you suspect coeliac disease, do not exclude gluten before GP-coordinated testing. Similarly, seek medical advice for suspected food allergies or significant adverse reactions.

Some practitioners advocate postprandial glucose monitoring—measuring blood sugar responses after meals with different macronutrient compositions. However, NICE guidance does not recommend routine self-monitoring for people without diabetes, and interpretation can be misleading without clinical context. If you have diabetes or metabolic concerns, discuss such monitoring with your GP or diabetes specialist nurse before proceeding independently.

Understanding the Three Main Metabolic Types

Metabolic typing systems typically classify individuals into three primary categories, each with distinct nutritional requirements and physiological characteristics. Understanding these classifications can provide a framework for dietary experimentation, though individual variation means not everyone fits neatly into a single category.

Protein types are characterised by what proponents describe as a fast oxidation rate (though this is not a clinically validated measure) and typically have strong appetites with frequent hunger. These individuals often experience energy crashes after high-carbohydrate meals and may feel anxious or jittery when consuming excessive sugar or refined carbohydrates. Protein types generally report feeling more satisfied and energised with meals containing substantial protein and healthy fats. They may have a higher tolerance for rich, heavy foods and often crave salty or fatty options. The theoretical suggestion includes higher proportions of protein and fat with moderate carbohydrates, though these are not evidence-based recommendations.

Carbohydrate types are described as having slower oxidation rates and may have relatively weak appetites. These individuals often feel satisfied with lighter meals and may experience digestive discomfort with excessive protein or fat. They generally tolerate and thrive on higher-carbohydrate diets, particularly from whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Carbohydrate types may have sweet cravings and typically feel energised rather than sluggish after carbohydrate-rich meals.

Mixed types fall between these extremes, demonstrating balanced responses to various macronutrients. These individuals typically function well with relatively equal proportions of protein, carbohydrates, and fats. They may have average appetites and generally tolerate diverse dietary patterns without extreme responses.

It bears emphasising that these categories represent theoretical constructs rather than validated medical diagnoses. The NHS Eatwell Guide provides evidence-based recommendations for a balanced diet suitable for most people. Any significant deviation from standard dietary guidance should be discussed with healthcare professionals, particularly for those with chronic kidney disease, liver disease, cardiovascular conditions, during pregnancy, or for adolescents and older adults. Individual responses vary considerably, and factors such as activity level, stress, sleep quality, and underlying health conditions significantly influence nutritional requirements.

Clinical Testing and Professional Assessment Options

For those seeking more objective data about their metabolic function, several clinical tests can provide valuable insights, though these assess actual metabolic health rather than confirming metabolic typing categories specifically.

Standard NHS blood tests offer foundational metabolic information. These typically include fasting glucose, HbA1c (glycated haemoglobin), lipid profile (cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, LDL), kidney function (U&Es, eGFR), liver function tests (LFTs), and full blood count (FBC). Thyroid function tests usually measure TSH and free T4; free T3 is not routinely checked in primary care. These tests can identify conditions such as diabetes (HbA1c ≥48 mmol/mol), non-diabetic hyperglycaemia (HbA1c 42-47 mmol/mol, sometimes called prediabetes), dyslipidaemia, or thyroid disorders that genuinely affect metabolism. Request these through your GP if you have concerns about weight management, energy levels, or metabolic health.

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices track blood glucose responses to foods in real-time over 10-14 days. NICE recommends CGM for specific groups of people with diabetes, not for general wellness use. While some individuals use CGM to understand their glycaemic responses to different meals, interpretation requires clinical context, and the technology is not routinely available on the NHS for those without diabetes.

Resting metabolic rate (RMR) testing, available through some private clinics and sports science facilities, measures oxygen consumption to calculate how many calories your body burns at rest. This provides accurate baseline metabolic information useful for weight management but doesn't categorise you into metabolic types.

Genetic testing services now offer nutrigenomics panels examining genes related to macronutrient metabolism, vitamin requirements, and food sensitivities. However, the clinical utility of such testing remains debated, with limited evidence that genetic information significantly improves dietary outcomes compared to standard nutritional guidance.

Before pursuing private testing, consult your GP to rule out underlying medical conditions. For personalised dietary advice, seek support from HCPC-registered dietitians (RD) or Association for Nutrition (AfN) registered nutritionists (RNutr/ANutr) who can provide evidence-based personalised nutrition advice. The British Dietetic Association's 'Find a Dietitian' service and the AfN Register can help locate qualified professionals who offer scientifically grounded nutritional assessment and guidance tailored to your individual health status and goals.

Applying Metabolic Type Knowledge to Your Diet and Lifestyle

Regardless of whether metabolic typing represents validated science, the principle of personalising nutrition based on individual responses offers practical value. The key lies in systematic experimentation and mindful observation rather than rigid adherence to categorical prescriptions.

Start with a baseline assessment by maintaining your current diet for one week whilst recording detailed information about meals, portion sizes, timing, and subsequent energy levels, mood, hunger patterns, and any physical symptoms. This establishes your starting point and highlights patterns you may not have consciously noticed.

Experiment with macronutrient ratios by adjusting one variable at a time. For example, if you suspect you might benefit from more protein, try increasing protein and healthy fats at breakfast whilst reducing refined carbohydrates, then monitor your mid-morning energy and appetite. Continue this meal composition if it improves your wellbeing, or adjust if symptoms worsen. Allow at least 3-5 days for each dietary modification before drawing conclusions, as immediate responses may not reflect sustained effects.

Prioritise food quality regardless of metabolic type. Focus on:

-

Whole, minimally processed foods rather than refined alternatives

-

Adequate protein from diverse sources (lean meats, fish, legumes, dairy)

-

Healthy fats including omega-3 fatty acids from oily fish, nuts, seeds, and olive oil

-

Complex carbohydrates from vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes

-

Sufficient fibre (30g daily as per UK guidelines) for digestive and metabolic health

Consider lifestyle factors that profoundly influence metabolism beyond diet alone. Regular physical activity, including the UK Chief Medical Officers' recommendation of 150 minutes of moderate activity plus strength training twice weekly, supports metabolic health. Resistance training helps improve muscle mass and glycaemic control. Adequate sleep (7-9 hours) supports hormonal balance and glucose metabolism. Stress management techniques help regulate cortisol, which affects appetite and fat storage. Hydration supports all metabolic processes.

Monitor and adjust your approach based on objective outcomes such as sustained energy levels, stable mood, healthy weight maintenance, good sleep quality, and absence of digestive discomfort. If you have existing medical conditions, particularly diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or kidney problems, discuss dietary changes with your GP or specialist before making significant modifications.

Seek medical advice promptly if you experience concerning symptoms such as unexplained weight loss, excessive thirst or urination, persistent digestive issues, extreme fatigue, significant mood changes, menstrual irregularities, or signs of disordered eating. These may indicate underlying conditions requiring medical assessment rather than dietary adjustment.

Remember that nutritional needs evolve with age, activity level, health status, and life circumstances. What works optimally now may require adjustment in future. The goal is developing nutritional awareness and flexibility rather than finding a permanent, unchanging dietary formula.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is metabolic typing scientifically validated?

Metabolic typing lacks robust scientific validation through large-scale clinical trials and is not endorsed by UK health bodies including NICE, the NHS, or the British Dietetic Association. Whilst individual metabolic variation is well-established in medical science, the specific categorisation systems used in metabolic typing have not been clinically validated.

What are the three main metabolic types?

The three theoretical metabolic types are protein types (who reportedly thrive on higher protein and fat), carbohydrate types (who tolerate higher carbohydrate intake), and mixed types (who function well with balanced macronutrients). These represent theoretical constructs rather than validated medical diagnoses.

What NHS tests can assess my metabolic health?

Standard NHS blood tests available through your GP include fasting glucose, HbA1c, lipid profile, kidney function, liver function tests, thyroid function tests, and full blood count. These can identify genuine metabolic conditions such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, and dyslipidaemia that affect metabolism.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript