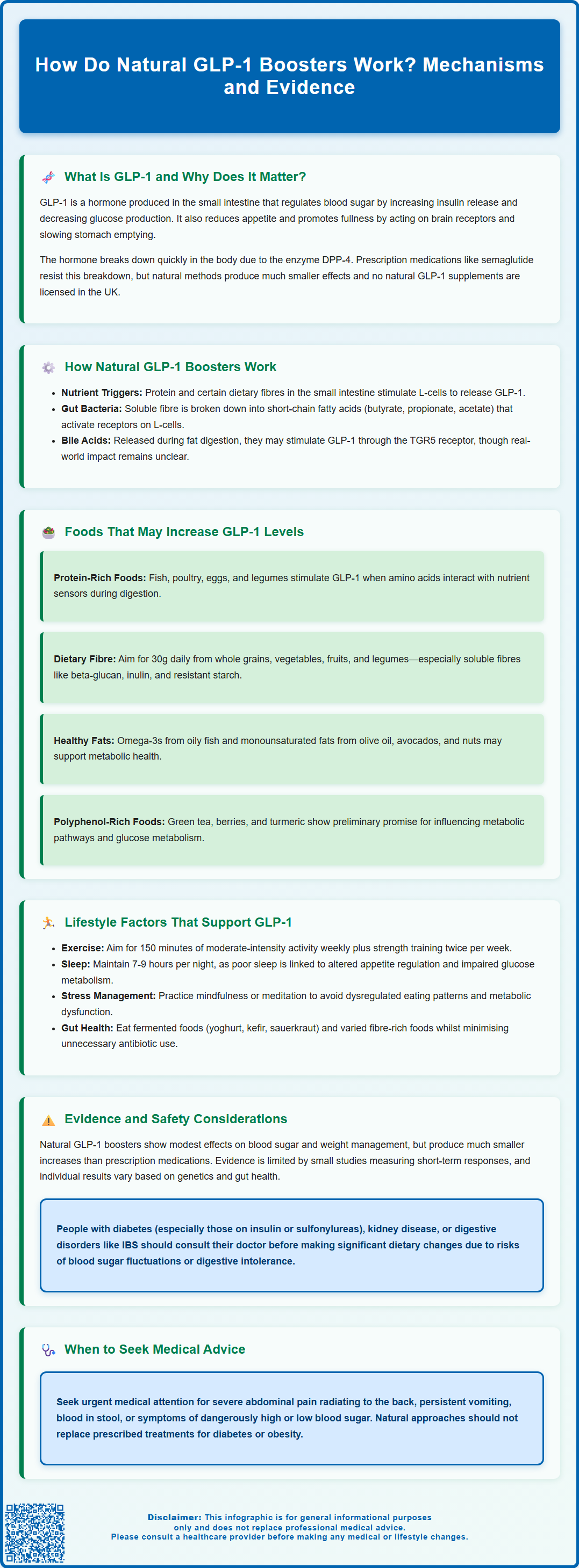

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a naturally occurring hormone that regulates blood glucose, appetite, and metabolism. Whilst pharmaceutical GLP-1 receptor agonists such as semaglutide are licensed for type 2 diabetes and weight management, there is growing interest in natural approaches to support the body's own GLP-1 production. Natural GLP-1 boosters work primarily through dietary components—particularly protein, fibre, and certain bioactive compounds—that stimulate intestinal L-cells to release this beneficial hormone. However, it is important to recognise that natural methods produce modest effects compared to pharmaceutical interventions, and no 'natural GLP-1 booster' supplements are licensed in the UK. This article explores the mechanisms, evidence, and practical considerations for supporting natural GLP-1 production through diet and lifestyle.

Summary: Natural GLP-1 boosters work by stimulating intestinal L-cells to produce and secrete GLP-1 through nutrient sensing, particularly via dietary fibre fermentation into short-chain fatty acids and protein-triggered signalling pathways.

- GLP-1 is an incretin hormone that enhances insulin secretion, suppresses glucagon, slows gastric emptying, and promotes satiety in a glucose-dependent manner.

- Dietary fibre undergoes bacterial fermentation to produce short-chain fatty acids that bind to L-cell receptors (FFAR2 and FFAR3), directly stimulating GLP-1 release.

- Protein-rich foods and certain bioactive compounds may increase postprandial GLP-1 secretion, though effects are modest compared to pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists.

- Natural approaches through whole foods and lifestyle modifications are generally safe but should not replace prescribed medications for type 2 diabetes or obesity.

- Individuals with diabetes should consult their GP before making significant dietary changes, as alterations may affect blood glucose control and medication requirements.

Table of Contents

What Is GLP-1 and Why Does It Matter for Health?

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a naturally occurring hormone produced primarily by specialised cells in the small intestine called L-cells. This incretin hormone plays a crucial role in regulating blood glucose levels, appetite, and energy metabolism. When food enters the digestive system, GLP-1 is released into the bloodstream, where it exerts multiple beneficial effects on metabolic health, though it has a very short half-life due to rapid degradation by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4).

The primary function of GLP-1 is to enhance insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner. This means insulin is released only when blood glucose levels are elevated, reducing the risk of hypoglycaemia. Simultaneously, GLP-1 suppresses glucagon secretion (also in a glucose-dependent manner), preventing excessive glucose production by the liver.

Beyond glucose regulation, GLP-1 significantly influences appetite and satiety. It acts on receptors in the brain, particularly in the hypothalamus and brainstem, to promote feelings of fullness and reduce food intake. Additionally, GLP-1 slows gastric emptying, prolonging the time food remains in the stomach and contributing to sustained satiety after meals.

The clinical importance of GLP-1 has been highlighted by the development of GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as semaglutide and liraglutide) for managing type 2 diabetes and, under specific NICE criteria, for weight management. These pharmaceutical agents mimic the action of natural GLP-1 but are resistant to rapid degradation. Understanding how to support the body's own GLP-1 production through natural means has therefore become an area of interest for metabolic health, though it is important to recognise that natural approaches produce more modest effects compared to pharmaceutical interventions. There are no licensed 'natural GLP-1 booster' supplements in the UK.

How Do Natural GLP-1 Boosters Work in the Body?

Natural GLP-1 boosters work through several interconnected mechanisms that stimulate the intestinal L-cells to produce and secrete more of this beneficial hormone. The most well-established pathway involves nutrient sensing in the gastrointestinal tract. When specific nutrients reach the small intestine, they interact with receptors on L-cells, triggering GLP-1 release. Different macronutrients activate distinct signalling pathways, with protein and certain types of dietary fibre being particularly effective stimulators.

Dietary fibre, especially soluble and fermentable types, undergoes bacterial fermentation in the colon, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These SCFAs bind to specific receptors on L-cells, notably the free fatty acid receptors FFAR2 and FFAR3, which directly stimulate GLP-1 secretion. This mechanism explains why high-fibre diets are associated with improved metabolic health and better glycaemic control, as supported by the UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) recommendations on fibre intake.

Another mechanism involves bile acids, which are released during fat digestion. Laboratory and animal studies suggest bile acids can activate the TGR5 receptor on L-cells, potentially promoting GLP-1 release. This pathway is influenced by the gut microbiome, as intestinal bacteria modify bile acid composition. However, the clinical significance of this pathway through dietary interventions in humans remains uncertain.

Polyphenols and other bioactive compounds found in plant foods have been studied for potential effects on GLP-1 secretion through various mechanisms, including modulation of gut microbiota composition and, in laboratory studies, inhibition of DPP-4. However, the evidence for clinically meaningful effects on GLP-1 levels from dietary polyphenols alone is preliminary, and any effects are likely to be modest compared to pharmaceutical interventions.

Foods and Nutrients That May Increase GLP-1 Levels

Several dietary components have been studied for their potential to enhance natural GLP-1 production, though it is important to note that effects are generally modest compared to pharmaceutical interventions. Protein-rich foods can stimulate GLP-1 secretion. Research suggests that protein intake, particularly from sources such as fish, poultry, eggs, and legumes, may increase postprandial GLP-1 secretion. The amino acids released during protein digestion interact with nutrient sensors on L-cells, triggering hormone release.

Dietary fibre from whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and legumes represents another key category, aligning with NHS and SACN recommendations for 30g of fibre daily. Soluble fibres such as beta-glucan (found in oats and barley), inulin (in chicory root, Jerusalem artichokes, and onions), and resistant starch (in cooked and cooled potatoes, green bananas, and legumes) are particularly beneficial. These fibres resist digestion in the small intestine and reach the colon, where they are fermented by beneficial bacteria to produce SCFAs that stimulate GLP-1 release.

Healthy fats, particularly omega-3 fatty acids found in oily fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines), have been studied in relation to metabolic health, though the evidence specifically for GLP-1 enhancement is less robust than for protein and fibre. Some studies suggest that monounsaturated fats from sources like olive oil, avocados, and nuts may have beneficial effects on overall metabolic health.

Certain polyphenol-rich foods have shown promise in preliminary research:

-

Green tea contains catechins that may influence metabolic pathways

-

Berries (blueberries, strawberries, blackberries) provide anthocyanins with potential metabolic benefits

-

Turmeric (curcumin) has been investigated for effects on glucose metabolism

It is crucial to emphasise that while these foods may support natural GLP-1 production, there is no official link established between consuming specific foods and clinically significant increases in GLP-1 comparable to pharmaceutical treatments. A balanced, whole-food diet incorporating these elements is recommended for overall metabolic health rather than targeting isolated nutrients, in line with NICE and NHS dietary guidance.

Lifestyle Factors That Support Natural GLP-1 Production

Beyond dietary choices, several lifestyle factors may influence the body's natural GLP-1 production and activity, though the evidence base varies in strength across different interventions. Physical activity has been studied in relation to GLP-1 levels, with mixed findings. Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise may support metabolic health and potentially affect GLP-1 secretion, though the relationship is complex. The UK Chief Medical Officers recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity weekly, plus strength exercises on at least two days per week, for overall health benefits including metabolic function.

Sleep quality and duration appear to play important roles in metabolic hormone regulation. Sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality have been associated with altered appetite regulation and impaired glucose metabolism. Whilst direct mechanistic links to GLP-1 are still being investigated, the NHS recommends maintaining consistent sleep patterns of 7–9 hours per night for overall health, including metabolic wellbeing.

Stress management may indirectly influence metabolic function through effects on cortisol and other stress hormones that affect glucose metabolism and appetite regulation. Chronic stress is associated with dysregulated eating patterns and metabolic dysfunction. Techniques such as mindfulness, meditation, or other stress-reduction strategies may support healthier metabolic function, though there is no established direct link between stress reduction and GLP-1 enhancement.

Meal timing and eating patterns may influence hormone secretion patterns. Some research suggests that consistent meal patterns may support metabolic health. Time-restricted eating (consuming food within a specific daily window) has been studied for potential metabolic effects, though NICE does not routinely recommend specific timing approaches for weight management. People with diabetes should consult their healthcare team before making significant changes to meal timing, as this may affect medication requirements and glucose control.

The gut microbiome composition may influence GLP-1 production through SCFA generation and bile acid metabolism. Factors that support a diverse, healthy microbiome—including consuming fermented foods (yoghurt, kefir, sauerkraut), minimising unnecessary antibiotic use, and eating a varied, fibre-rich diet—may indirectly support metabolic health. Probiotic supplementation has shown mixed results in research, and there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend specific strains for GLP-1 enhancement.

Evidence and Safety Considerations for Natural Approaches

The evidence supporting natural GLP-1 boosters varies considerably in quality and clinical significance. Most research has focused on dietary patterns and individual nutrients, with findings generally showing modest effects on GLP-1 levels and metabolic outcomes. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggest that high-fibre, high-protein diets can improve glycaemic control and support weight management, though it remains unclear how much of this benefit is directly attributable to enhanced GLP-1 secretion versus other mechanisms.

Important limitations in the current evidence base include:

-

Most studies measure acute GLP-1 responses to single meals rather than long-term effects

-

Sample sizes are often small, and study populations vary widely

-

The magnitude of GLP-1 increase from dietary interventions is substantially smaller than that achieved with pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists

-

Individual responses vary considerably based on genetics, baseline metabolic health, and gut microbiome composition

From a safety perspective, natural approaches to supporting GLP-1 production through whole foods and lifestyle modifications are generally considered safe for most individuals. Unlike pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists, which can cause gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea, dietary approaches rarely produce significant adverse effects when implemented gradually. However, individuals should be aware that rapidly increasing fibre intake can cause temporary bloating, gas, and digestive discomfort. Gradual increases over several weeks are recommended.

Clinical considerations for specific populations:

-

Individuals with diabetes should consult their GP or diabetes specialist before making significant dietary changes, as alterations in carbohydrate intake and meal timing may affect blood glucose control and medication requirements

-

Those taking insulin or sulfonylureas should be particularly cautious, as dietary changes may increase the risk of hypoglycaemia

-

Those with kidney disease should seek medical advice before substantially increasing protein intake

-

People with digestive disorders (such as irritable bowel syndrome) may need to modify fibre recommendations based on individual tolerance

Seek urgent medical attention for severe abdominal pain (especially if radiating to the back), persistent vomiting, blood in stool, or symptoms of hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia.

It is crucial to emphasise that natural approaches to supporting GLP-1 should not be considered substitutes for prescribed medications in individuals with type 2 diabetes or obesity requiring pharmaceutical intervention. NICE guidelines recommend lifestyle modifications as foundational therapy, but many patients require additional pharmacological treatment to achieve glycaemic targets or clinically significant weight loss.

If you experience side effects from any medication, report them through the MHRA Yellow Card scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk). Natural approaches are best viewed as complementary strategies that support overall metabolic health rather than targeted treatments for specific conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can natural foods increase GLP-1 levels as effectively as medications?

No, natural dietary approaches produce modest increases in GLP-1 compared to pharmaceutical GLP-1 receptor agonists. Whilst high-fibre and high-protein foods can support natural GLP-1 production, the magnitude of effect is substantially smaller than licensed medications such as semaglutide or liraglutide.

What foods are best for supporting natural GLP-1 production?

Protein-rich foods (fish, poultry, eggs, legumes), soluble fibres (oats, barley, vegetables, fruits), and fermentable fibres (resistant starch from cooked and cooled potatoes, green bananas) are most effective. These stimulate intestinal L-cells through nutrient sensing and short-chain fatty acid production from bacterial fermentation.

Are natural GLP-1 boosters safe for people with diabetes?

Natural approaches through whole foods are generally safe, but individuals with diabetes should consult their GP or diabetes specialist before making significant dietary changes. Alterations in carbohydrate intake and meal timing may affect blood glucose control and medication requirements, particularly for those taking insulin or sulfonylureas.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript