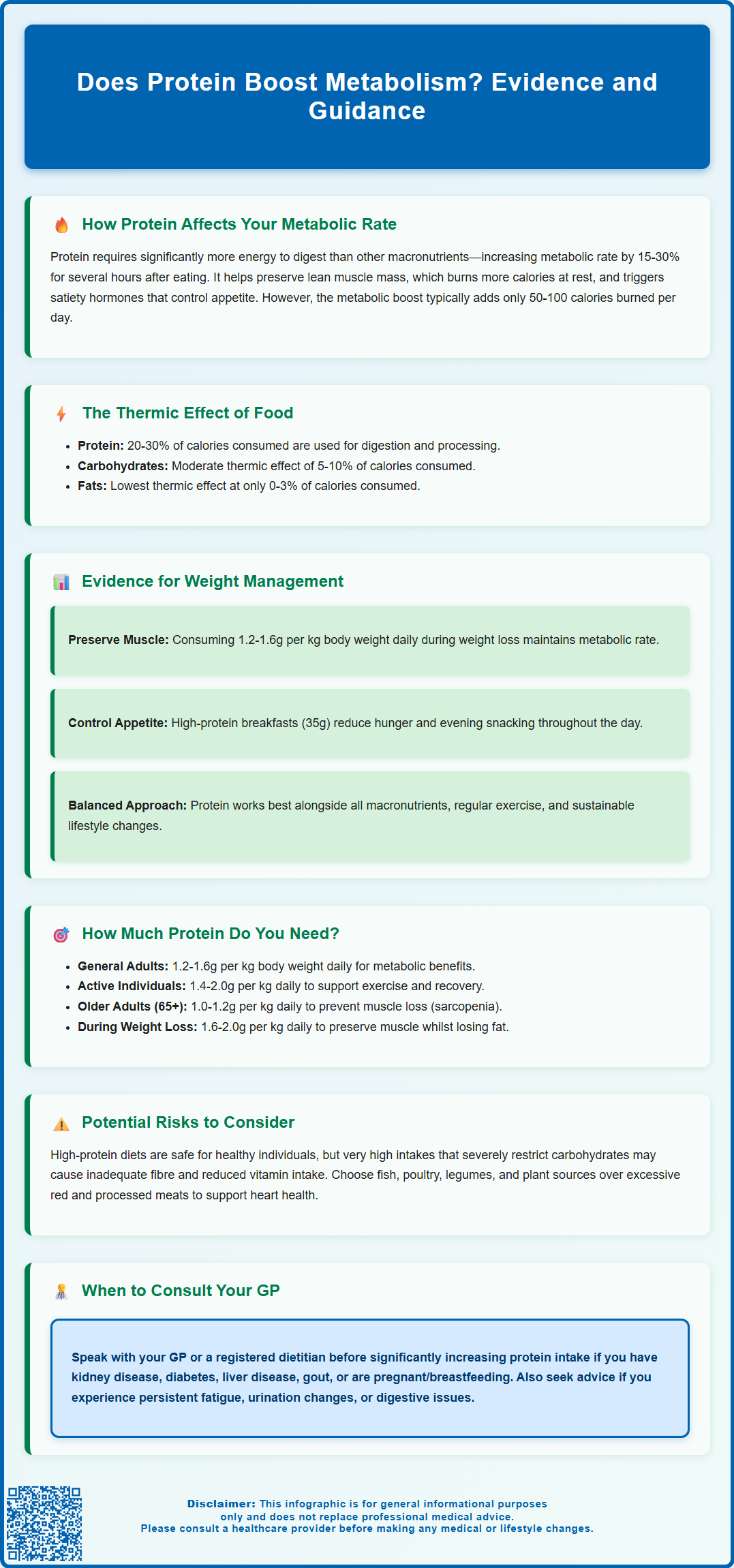

Does protein boost metabolism? This question is central to understanding how dietary choices influence energy expenditure and weight management. Protein does indeed increase metabolic rate through several physiological mechanisms, primarily via the thermic effect of food—the energy required to digest, absorb, and process nutrients. Compared to carbohydrates and fats, protein requires substantially more energy to metabolise, typically increasing metabolic rate by 15–30% for several hours after consumption. Additionally, protein helps preserve lean muscle mass and influences appetite-regulating hormones. Whilst protein offers measurable metabolic benefits, these effects work best as part of a balanced dietary approach aligned with NHS and NICE guidance on nutrition and weight management.

Summary: Protein does boost metabolism by increasing energy expenditure through the thermic effect of food, requiring 20–30% of consumed calories for digestion and processing compared to 5–10% for carbohydrates and 0–3% for fats.

- Protein increases metabolic rate by approximately 15–30% for several hours after consumption through diet-induced thermogenesis.

- Higher protein intake (1.2–1.6 g/kg body weight daily) helps preserve lean muscle mass during weight loss, maintaining metabolic rate.

- Protein stimulates satiety hormones (PYY, GLP-1) and reduces ghrelin, improving appetite control and potentially reducing spontaneous energy intake.

- The UK Reference Nutrient Intake for protein is 0.75 g/kg daily, though higher intakes may benefit metabolic health and weight management.

- Individuals with chronic kidney disease, diabetes, or gout should consult their GP before significantly increasing protein intake, as requirements vary.

Table of Contents

How Protein Affects Your Metabolic Rate

Protein does indeed influence metabolic rate through several distinct physiological mechanisms. When you consume protein, your body must work harder to digest, absorb, and process it compared to other macronutrients. This increased energy expenditure is measurable and contributes to overall daily energy expenditure.

The metabolic impact of protein occurs over several hours after consumption. Dietary protein stimulates protein synthesis, a highly energy-demanding process that requires ATP (adenosine triphosphate). Additionally, protein helps preserve lean muscle mass, which is metabolically active tissue. Muscle tissue burns more calories at rest than adipose (fat) tissue, though the difference is modest—individuals with greater muscle mass typically have slightly higher resting metabolic rates.

Protein also influences several hormones that regulate metabolism and appetite. It stimulates the release of satiety hormones such as peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), whilst reducing levels of ghrelin, the hunger hormone. This hormonal response not only affects immediate appetite but also influences how efficiently the body utilises energy throughout the day.

Research demonstrates that high-protein meals can increase metabolic rate by approximately 15-30% for several hours after eating, compared to 5-10% for carbohydrates and 0-3% for fats. However, it is important to note that whilst protein does boost metabolism, this effect alone typically adds only 50-100 kcal (calories) per day and is unlikely to result in dramatic weight loss without consideration of overall energy intake and balance. The metabolic advantage of protein should be viewed as one component of a comprehensive approach to nutrition and weight management.

The Thermic Effect of Food: Protein vs Other Macronutrients

The thermic effect of food (TEF), also known as diet-induced thermogenesis, refers to the energy required to digest, absorb, and process nutrients from food. This represents approximately 10% of total daily energy expenditure in most individuals, though this varies considerably depending on macronutrient composition.

Protein demonstrates a substantially higher thermic effect compared to carbohydrates and fats. Specifically:

-

Protein: 20-30% of kcal (calories) consumed are used in processing

-

Carbohydrates: 5-10% of kcal (calories) consumed are used in processing

-

Fats: 0-3% of kcal (calories) consumed are used in processing

This means that if you consume 100 kcal from protein, approximately 20-30 of those kcal are expended simply processing that protein, leaving a net energy gain of 70-80 kcal. In contrast, 100 kcal from fat would require only 0-3 kcal to process, resulting in a net gain of 97-100 kcal.

The mechanisms underlying protein's high thermic effect are multifaceted. Deamination (removal of amino groups from amino acids) and gluconeogenesis (conversion of amino acids to glucose) are both energy-intensive processes. Additionally, the synthesis of new proteins from dietary amino acids requires significant ATP expenditure.

Clinical studies have consistently demonstrated this differential effect. Research published in peer-reviewed journals shows that individuals consuming higher-protein diets experience greater 24-hour energy expenditure compared to those consuming isocaloric diets with lower protein content. However, the absolute magnitude of this effect—whilst statistically significant—typically amounts to an additional 50-100 kcal per day in practical terms, which should be considered within the context of total energy balance and varies with individual factors such as body size and activity level.

Evidence for Protein's Role in Metabolism and Weight Management

A substantial body of evidence supports protein's beneficial role in weight management and metabolic health. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated that higher-protein diets facilitate greater fat loss whilst preserving lean muscle mass during calorie restriction.

A landmark study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that individuals consuming 1.2-1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily during weight loss retained significantly more muscle mass than those consuming lower amounts. Preservation of muscle mass is crucial because it helps maintain metabolic rate, which often declines during calorie restriction—a phenomenon known as metabolic adaptation.

Protein's satiating properties contribute substantially to its effectiveness in weight management. Clinical trials demonstrate that high-protein breakfasts reduce subsequent food intake throughout the day. Research shows that participants consuming a high-protein breakfast (35 grams) experienced reduced evening snacking and improved appetite control compared to those consuming a normal-protein breakfast.

Long-term studies provide further evidence. Research following participants over 12 months found that those assigned to higher-protein diets (25-30% of calories from protein) lost more weight and maintained greater weight loss compared to standard-protein groups (15% of calories from protein). Importantly, these benefits occurred even when total calorie intake was not explicitly restricted in some studies, suggesting protein's metabolic and appetite effects may contribute to spontaneous reduction in energy intake.

However, it is essential to note that protein is not a 'magic bullet' for weight loss. The evidence indicates protein works best as part of a balanced dietary approach that includes appropriate portions of all macronutrients, regular physical activity, and sustainable lifestyle modifications, in line with NHS and NICE guidance on weight management. Individual responses vary, and what works optimally for one person may differ for another.

How Much Protein Do You Need for Metabolic Benefits?

The optimal protein intake for metabolic benefits depends on several factors, including age, activity level, body composition goals, and overall health status. Current UK guidance provides a foundation, though emerging evidence suggests higher intakes may be beneficial for specific populations.

The UK Reference Nutrient Intake (RNI) for protein is 0.75 grams per kilogram of body weight daily for adults, as established by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. For a 70-kilogram adult, this equates to approximately 52.5 grams daily. However, this represents the minimum intake to prevent deficiency rather than the optimal amount for metabolic health or body composition.

For metabolic benefits and weight management, research suggests higher intakes may be advantageous:

-

General population: 1.2-1.6 g/kg body weight daily

-

Active individuals: 1.4-2.0 g/kg body weight daily

-

Older adults (>65 years): 1.0-1.2 g/kg body weight daily (to combat sarcopenia)

-

During calorie restriction: 1.6-2.0 g/kg body weight daily (to preserve muscle mass)

For people with obesity, calculating protein needs based on a target or adjusted body weight rather than actual weight may be more appropriate to avoid excessive absolute intakes.

Distribution throughout the day also matters. Evidence suggests consuming 20-30 grams of protein per meal optimally stimulates muscle protein synthesis in younger adults. Older adults may benefit from 25-40 grams per meal due to age-related anabolic resistance. This approach, rather than consuming most protein in one meal, appears to maximise metabolic benefits.

Practical protein sources include lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, nuts, and seeds. For a 70-kilogram individual targeting 1.6 g/kg (112 grams daily), this might include: two eggs at breakfast (12g), a chicken breast at lunch (30g), Greek yoghurt as a snack (15g), and salmon with quinoa at dinner (35g), with additional protein from plant sources throughout the day.

If you have existing kidney disease, diabetes, gout, or other chronic conditions, consult your GP or a registered dietitian before significantly increasing protein intake, as individual requirements and tolerances vary. Pregnant or breastfeeding women should also seek advice from their midwife, GP or dietitian before making significant dietary changes.

Potential Risks of High-Protein Diets

Whilst protein offers metabolic benefits, excessively high protein intake may pose risks for certain individuals. It is crucial to understand these potential concerns and recognise when medical advice is warranted.

Kidney function is the primary concern with very high protein intakes. The kidneys must process nitrogen waste products from protein metabolism. For individuals with pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD), protein intake typically needs to be carefully managed. NICE guidance (NG203) recommends that people with CKD should be referred to a renal dietitian for individualised advice on protein intake. However, current evidence suggests that high protein intake does not cause kidney damage in healthy individuals with normal kidney function. If you have known kidney disease or risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, family history), discuss protein intake with your GP before making significant dietary changes.

Bone health was historically a concern, based on the theory that high protein intake increases calcium excretion. However, more recent research indicates that adequate protein intake actually supports bone health, particularly in older adults. The key is ensuring sufficient calcium intake alongside higher protein consumption.

Nutritional balance can be compromised if protein displaces other essential nutrients. Very high-protein diets that severely restrict carbohydrates may lead to:

-

Inadequate fibre intake, causing constipation

-

Reduced intake of important vitamins and minerals found in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains

-

Decreased dietary variety, making the diet difficult to sustain long-term

Cardiovascular considerations depend on protein sources. Diets high in red and processed meats have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk, partly due to their saturated fat and salt content. The NHS advises limiting red and processed meat consumption, whilst protein from fish, poultry, legumes, and plant sources appears neutral or beneficial for heart health.

Gout management may require protein modification. NICE guidance (NG219) for gout recommends individualised dietary advice, which may include moderating intake of certain high-purine protein sources.

When to seek medical advice: Contact your GP if you experience persistent fatigue, changes in urination, unexplained weight changes, or digestive issues after increasing protein intake. Individuals with diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, or gout should consult healthcare professionals before adopting high-protein diets, as these conditions may require modified protein recommendations.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much does protein increase metabolism compared to other nutrients?

Protein increases metabolic rate by approximately 15–30% for several hours after eating, compared to 5–10% for carbohydrates and 0–3% for fats. This thermic effect means 20–30% of calories from protein are used in digestion and processing, compared to only 0–3% for fats.

How much protein should I consume daily for metabolic benefits?

For metabolic benefits and weight management, research suggests 1.2–1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight daily for the general population, with higher amounts (1.6–2.0 g/kg) during calorie restriction to preserve muscle mass. The UK Reference Nutrient Intake is 0.75 g/kg daily, representing minimum requirements to prevent deficiency.

Are there any risks associated with high-protein diets?

Individuals with chronic kidney disease, diabetes, or gout should consult their GP before significantly increasing protein intake, as these conditions may require modified recommendations. Very high-protein diets may also compromise nutritional balance if they displace fibre, vitamins, and minerals from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript