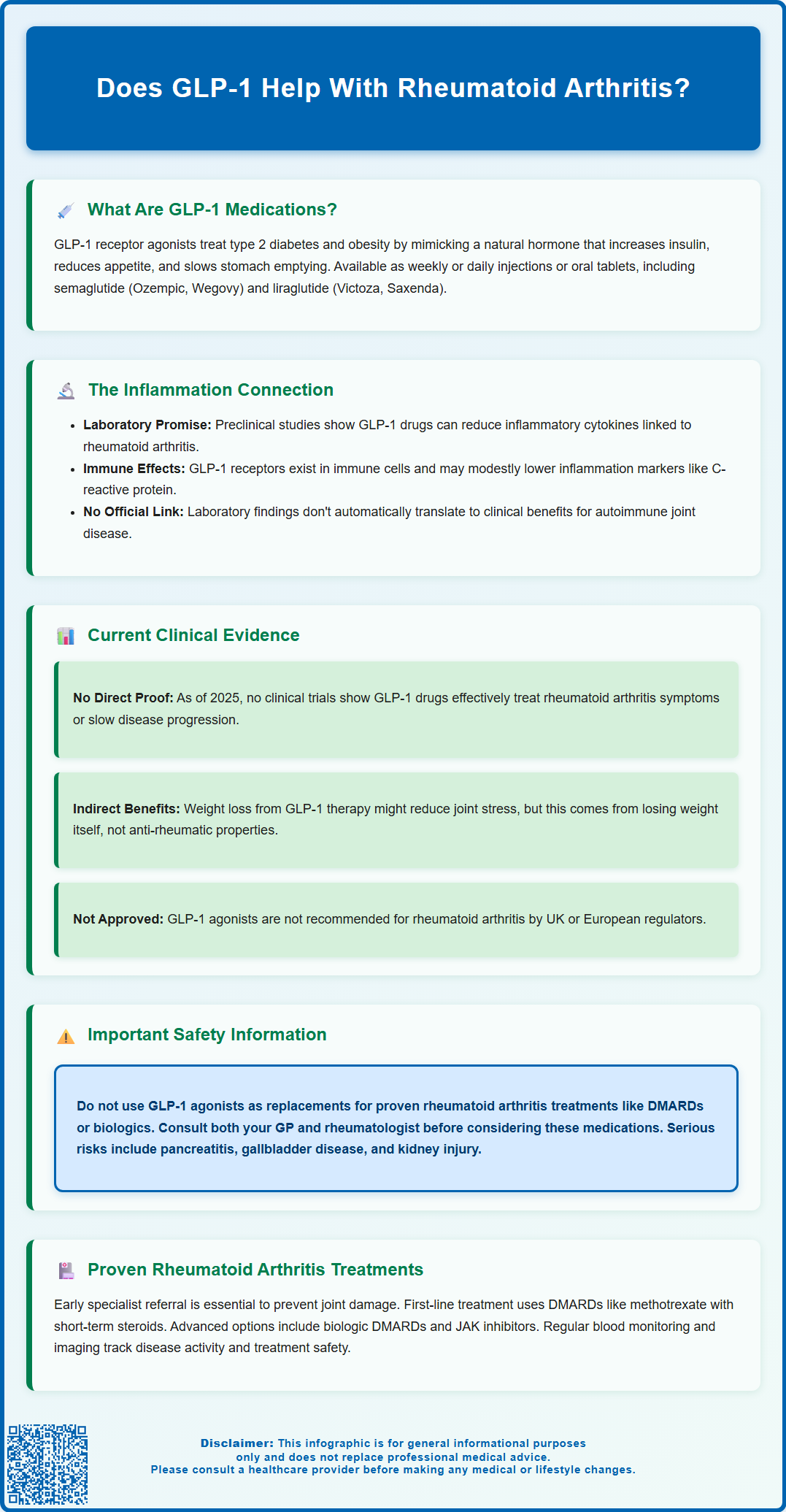

GLP-1 receptor agonists are medications licensed in the UK for type 2 diabetes and obesity management. Whilst emerging research suggests these drugs may have anti-inflammatory properties, there is currently no established evidence supporting their use for rheumatoid arthritis. This article examines the theoretical mechanisms, reviews available clinical data, and clarifies why GLP-1 agonists are not recommended for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis should continue evidence-based therapies including disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic agents as recommended by NICE guidance.

Summary: GLP-1 receptor agonists are not established treatments for rheumatoid arthritis and lack clinical evidence supporting their use in this condition.

- GLP-1 agonists are licensed only for type 2 diabetes and obesity, not rheumatoid arthritis or other autoimmune conditions.

- Preclinical studies suggest potential anti-inflammatory effects, but no randomised controlled trials have evaluated GLP-1 agonists for rheumatoid arthritis treatment.

- These medications are not recommended by NICE, MHRA, or EMA for rheumatoid arthritis management.

- Established rheumatoid arthritis treatment requires disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate, with biologic therapies for inadequate responders.

- Patients with rheumatoid arthritis require specialist rheumatology assessment and should not substitute GLP-1 agonists for evidence-based therapies.

- Any patient with joint symptoms should consult their GP or rheumatologist for appropriate diagnosis and treatment according to NICE guidance (NG100).

Table of Contents

What Are GLP-1 Medications and How Do They Work?

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a class of medications primarily licensed for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus and, more recently, obesity. These medicines work by mimicking the action of a naturally occurring hormone called GLP-1, which is released from the intestine in response to food intake.

The mechanism of action involves several key physiological effects. GLP-1 agonists bind to GLP-1 receptors on pancreatic beta cells, stimulating insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner—meaning they only promote insulin release when blood glucose levels are elevated. This reduces the risk of hypoglycaemia compared to some other diabetes medications, though this risk increases when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas. Additionally, these drugs suppress glucagon secretion (a hormone that raises blood glucose), slow gastric emptying to reduce post-meal glucose spikes, and act on appetite centres in the brain to promote satiety and reduce food intake.

GLP-1 receptor agonists available in the UK include:

-

Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus)

-

Dulaglutide (Trulicity)

-

Liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda)

-

Exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon)

These medications are administered either as subcutaneous injections (weekly or daily, depending on the formulation) or as oral tablets (Rybelsus). According to NICE guidance (NG28), GLP-1 agonists are recommended for adults with type 2 diabetes who have not achieved adequate glycaemic control with other therapies. For weight management, NICE recommends specific GLP-1 agonists (TA875, TA664) for adults with a BMI of at least 35 kg/m² (or ≥30 kg/m² with weight-related comorbidities) and only through specialist weight management services.

Important safety considerations include risks of pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, worsening of diabetic retinopathy (particularly with rapid improvement in blood glucose), and potential kidney injury if dehydration occurs due to gastrointestinal side effects. Common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and injection site reactions. Suspected side effects should be reported via the MHRA Yellow Card scheme.

The Link Between GLP-1 Agonists and Inflammation

Beyond their established metabolic effects, emerging research suggests that GLP-1 receptor agonists may possess anti-inflammatory properties. GLP-1 receptors are not exclusively found in the pancreas; they are also expressed in various tissues throughout the body, including immune cells and vascular endothelium, with some preliminary evidence suggesting potential presence in synovial tissue.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that GLP-1 signalling can modulate inflammatory pathways. These medications appear to reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines—signalling molecules that drive inflammation—such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). These same cytokines play a central role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis, where they contribute to joint inflammation, cartilage degradation, and bone erosion.

Additionally, GLP-1 agonists have been shown to reduce markers of systemic inflammation, including C-reactive protein (CRP), in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, though these reductions are often modest. They may also improve endothelial function and reduce oxidative stress, both of which are implicated in chronic inflammatory conditions. Some research suggests these drugs can influence macrophage polarisation, shifting immune cells towards a less inflammatory phenotype.

However, it is important to emphasise that there is no official link established between GLP-1 agonists and the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. The anti-inflammatory effects observed in laboratory and cardiovascular studies do not automatically translate to clinical benefit in autoimmune joint disease. The mechanisms underlying rheumatoid arthritis are complex and multifactorial, involving adaptive immune responses that may not be adequately addressed by GLP-1 receptor modulation alone. These findings remain hypothesis-generating with uncertain clinical relevance to rheumatoid arthritis. Further targeted research is needed to determine whether these theoretical benefits have any meaningful impact on rheumatoid arthritis disease activity.

Current Evidence: GLP-1 Effects on Rheumatoid Arthritis Symptoms

As of 2025, there is limited direct clinical evidence examining the effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists specifically on rheumatoid arthritis symptoms or disease progression. Most available data comes from observational studies, post-hoc analyses, or research focused on metabolic outcomes in patients who happen to have coexisting inflammatory conditions.

Some observational studies have noted that patients with type 2 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis who were treated with GLP-1 agonists experienced modest reductions in inflammatory markers compared to those on other glucose-lowering therapies. However, these studies were not designed to assess rheumatoid arthritis-specific outcomes such as joint pain, swelling, Disease Activity Score (DAS28), or radiographic progression. The reductions in CRP and other inflammatory markers may simply reflect improved metabolic control rather than a direct effect on autoimmune joint inflammation.

A few small-scale studies have explored whether weight loss achieved through GLP-1 therapy might indirectly benefit patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Obesity is known to worsen rheumatoid arthritis outcomes by increasing mechanical stress on joints and promoting systemic inflammation through adipose tissue-derived cytokines. Weight reduction can therefore improve symptoms and reduce disease activity in some patients. However, this benefit would be attributable to weight loss itself rather than a specific anti-rheumatic effect of GLP-1 agonists.

There are currently no randomised controlled trials evaluating GLP-1 receptor agonists as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, and these medications are not licensed or recommended for this indication by the MHRA, NICE, or the European Medicines Agency (EMA). GLP-1 receptor agonists should only be used within their licensed indications and according to NICE criteria. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis should not consider GLP-1 agonists as an alternative to established disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or biologic therapies. Those with both type 2 diabetes/obesity and rheumatoid arthritis who are considering GLP-1 therapy should discuss this with both their GP and rheumatologist. Anyone experiencing joint symptoms should consult their GP or rheumatologist for appropriate assessment and evidence-based treatment.

Treatment Options for Rheumatoid Arthritis in the UK

Rheumatoid arthritis requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent irreversible joint damage and disability. NICE guidelines (NG100) recommend early referral to a rheumatology specialist for anyone with suspected persistent synovitis, particularly if multiple small joints are affected or if there is morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes.

The cornerstone of rheumatoid arthritis management is disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which suppress the underlying autoimmune process. First-line treatment typically involves:

-

Methotrexate – the most commonly prescribed conventional synthetic DMARD

-

Sulfasalazine or hydroxychloroquine – alternative or combination options

-

Leflunomide – for patients who cannot tolerate methotrexate

These medications are usually combined with short-term corticosteroids (such as prednisolone) to provide rapid symptom relief whilst DMARDs take effect, which can take several weeks to months.

For patients who do not respond adequately to conventional DMARDs, advanced therapies are available through NHS specialist services. These include:

- Biologic DMARDs:

- TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab)

- IL-6 inhibitors (tocilizumab, sarilumab)

- B-cell depleting agents (rituximab)

-

T-cell co-stimulation inhibitors (abatacept)

-

Targeted synthetic DMARDs:

- JAK inhibitors (baricitinib, tofacitinib, upadacitinib)

NICE provides specific criteria for accessing these treatments based on disease activity scores (typically DAS28 >5.1 for initial biologic therapy) and previous treatment responses. Before starting biologics or JAK inhibitors, patients require screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis B/C, and should receive appropriate vaccinations (avoiding live vaccines during treatment).

Regular monitoring is essential, including blood tests to assess disease activity (CRP, ESR), drug safety (liver and kidney function, blood counts), and periodic imaging to detect joint damage.

Non-pharmacological management is equally important and should include physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and patient education programmes. The NHS offers multidisciplinary support through rheumatology departments to help patients manage symptoms, maintain function, and prevent complications.

Patients should seek urgent same-day assessment if they develop a hot, swollen joint with fever or systemic unwellness, as this could indicate septic arthritis requiring immediate treatment. For less urgent concerns, patients should contact their GP or rheumatology team promptly if they experience worsening joint symptoms, new swelling, or signs of infection, as these may require assessment and treatment adjustment.

Scientific References

- Ozempic 0.5 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen - Summary of Product Characteristics.

- Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management (NG100).

- The effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists on circulating inflammatory markers: systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy.

- Immunomodulatory effects of anti-diabetic therapies: Cytokine and chemokine modulation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can GLP-1 receptor agonists treat rheumatoid arthritis?

No, GLP-1 receptor agonists are not licensed or recommended for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. There are no randomised controlled trials supporting their use in this condition, and patients should continue evidence-based therapies such as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) as recommended by NICE guidance.

Do GLP-1 medications have anti-inflammatory effects?

Preclinical studies suggest GLP-1 agonists may reduce certain inflammatory markers, but these findings have not been validated in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Any observed reductions in inflammation likely reflect improved metabolic control rather than specific anti-rheumatic effects.

What are the recommended treatments for rheumatoid arthritis in the UK?

NICE recommends disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate as first-line treatment, with biologic therapies (TNF inhibitors, IL-6 inhibitors) or JAK inhibitors for patients with inadequate response. Early referral to rheumatology is essential for prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent joint damage.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript