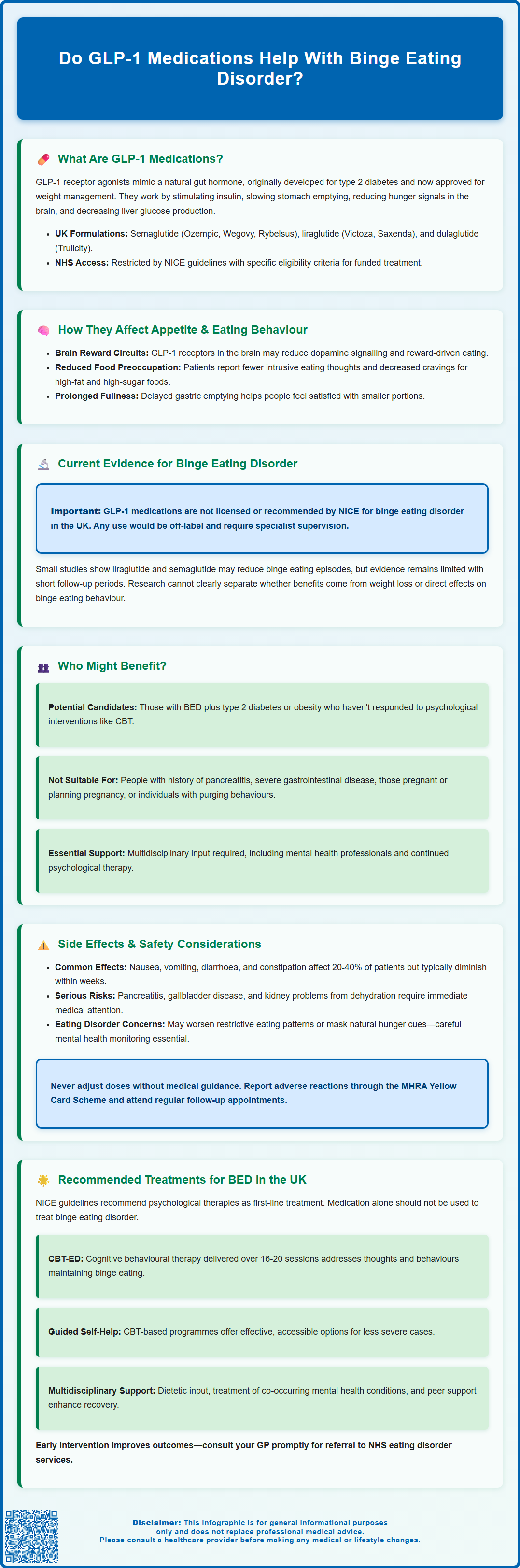

Binge eating disorder (BED) is a serious mental health condition characterised by recurrent episodes of consuming large quantities of food with a sense of loss of control. Whilst psychological therapies remain the recommended first-line treatment in the UK, emerging research suggests that GLP-1 receptor agonists—medications originally developed for type 2 diabetes and weight management—may influence eating behaviours beyond simple appetite suppression. These medicines work on brain reward pathways and satiety signals, potentially reducing food cravings and binge episodes. However, no GLP-1 medication currently holds a UK licence for treating binge eating disorder, and evidence remains preliminary. This article examines the current understanding of whether GLP-1 agonists help with binge eating, their mechanisms, safety considerations, and alternative evidence-based treatments available through the NHS.

Summary: GLP-1 receptor agonists show preliminary promise for reducing binge eating episodes, but they are not currently licensed or recommended for binge eating disorder in the UK.

- GLP-1 medications work on brain reward pathways and appetite centres, potentially reducing food cravings and loss-of-control eating beyond simple hunger suppression.

- Small studies suggest liraglutide and semaglutide may reduce binge eating frequency, but robust long-term evidence is lacking and no GLP-1 drug is licensed for this indication.

- NICE recommends cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT-ED) as first-line treatment for binge eating disorder, not medication alone.

- Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal symptoms; serious risks include pancreatitis and gallbladder disease requiring clinical monitoring.

- Any use of GLP-1 agonists for binge eating disorder is off-label and should involve specialist oversight with continued psychological support.

Table of Contents

- What Are GLP-1 Medications and How Do They Work?

- The Link Between GLP-1 Agonists and Appetite Control

- Current Evidence: Do GLP-1 Medications Help With Binge Eating?

- Who Might Benefit From GLP-1 Treatment for Binge Eating

- Potential Side Effects and Safety Considerations

- Alternative Treatments for Binge Eating Disorder in the UK

- Scientific References

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Are GLP-1 Medications and How Do They Work?

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a class of medications originally developed for managing type 2 diabetes and, more recently, approved for weight management. These medicines mimic the action of GLP-1, a naturally occurring hormone produced in the intestine in response to food intake. In the UK, commonly prescribed GLP-1 agonists include semaglutide (Ozempic® for type 2 diabetes, Rybelsus® as an oral option for type 2 diabetes, and Wegovy® for weight management), liraglutide (Victoza® for diabetes and Saxenda® for weight management), and dulaglutide (Trulicity® for diabetes).

The mechanism of action involves several physiological pathways. GLP-1 receptor agonists work by:

-

Stimulating insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner, which helps regulate blood sugar levels

-

Slowing gastric emptying, meaning food remains in the stomach longer, promoting feelings of fullness

-

Acting on appetite centres in the brain, particularly the hypothalamus, to reduce hunger signals and food cravings

-

Decreasing glucagon secretion, which helps prevent excessive glucose production by the liver

Most GLP-1 agonists are administered via subcutaneous injection, typically once weekly or once daily depending on the specific formulation, though oral semaglutide (Rybelsus®) is also available. While these medications have marketing authorisations for specific indications, NHS access is governed by NICE technology appraisals, which set narrower eligibility criteria than the marketing authorisation. For weight management, NICE TA875 (semaglutide) and TA664 (liraglutide) specify the patient groups eligible for NHS-funded treatment.

Whilst these medications have demonstrated significant efficacy in glycaemic control and weight reduction, their potential role in addressing disordered eating patterns, including binge eating, has emerged as an area of clinical and research interest. Understanding their fundamental mechanisms provides context for exploring their possible effects on eating behaviours beyond simple appetite suppression.

The Link Between GLP-1 Agonists and Appetite Control

The relationship between GLP-1 receptor agonists and appetite regulation extends beyond basic hunger suppression, involving complex neurobiological pathways that influence eating behaviour. Research suggests that GLP-1 receptors are present not only in the pancreas and gastrointestinal tract but also in key brain regions involved in reward processing and food motivation, including the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area, though much of this evidence comes from preclinical studies.

Central nervous system effects appear potentially relevant to understanding how these medications might influence binge eating patterns. Based on early human studies and animal research, GLP-1 agonists may affect:

-

Reward-related eating behaviours by potentially modulating dopamine signalling in brain reward circuits

-

Food cravings and hedonic eating (eating for pleasure rather than hunger)

-

Impulsivity around food, possibly reducing the compulsive aspects of eating

-

Satiety signalling, enhancing the feeling of fullness after meals

Some patients using GLP-1 medications for diabetes or weight management report not just reduced appetite but also diminished preoccupation with food, fewer intrusive thoughts about eating, and reduced cravings for specific foods, particularly those high in fat and sugar. These subjective experiences suggest the medications may influence the psychological and neurological drivers of eating beyond simple physiological hunger, though systematic studies confirming these effects are limited.

The delayed gastric emptying caused by GLP-1 agonists also contributes to prolonged satiation, which may help individuals feel satisfied with smaller portions and reduce the likelihood of consuming large quantities of food in a short period—a hallmark of binge eating episodes. However, it is important to note that whilst these mechanisms are promising, the specific application to binge eating disorder requires careful clinical evaluation, as this condition involves complex psychological, behavioural, and biological factors that extend beyond appetite regulation alone.

Current Evidence: Do GLP-1 Medications Help With Binge Eating?

The evidence base for GLP-1 receptor agonists specifically treating binge eating disorder (BED) remains limited but emerging. Currently, no GLP-1 medication holds a UK licence for binge eating disorder, and NICE has not issued guidance recommending their use for this indication. Any use of these medications for BED would be considered off-label and should be under specialist oversight. However, several research studies and clinical observations provide preliminary insights into their potential efficacy.

Clinical trial evidence includes small-scale studies and post-hoc analyses suggesting possible benefits. Research examining liraglutide in individuals with binge eating disorder and obesity has found reductions in binge eating episodes compared to placebo, alongside weight loss. Participants reported fewer binge days per week and improved eating-related psychological distress. Similarly, observational data from patients prescribed semaglutide for weight management have documented reductions in loss-of-control eating and binge-like behaviours.

However, important limitations exist in the current evidence:

-

Most studies have been relatively small with short follow-up periods

-

Many participants had concurrent obesity, making it difficult to separate weight loss effects from direct effects on binge eating behaviour

-

Long-term efficacy and safety data specifically for binge eating disorder are lacking

-

The psychological and behavioural components of BED may require interventions beyond pharmacological appetite suppression

There is no official link established by regulatory bodies between GLP-1 agonists and binge eating disorder treatment. The Royal College of Psychiatrists and eating disorder specialists emphasise that BED is a complex mental health condition requiring comprehensive assessment and typically multimodal treatment. NICE guideline NG69 (Eating disorders: recognition and treatment) recommends psychological therapies as first-line treatment. Whilst the neurobiological effects of GLP-1 medications on reward pathways and food-related impulsivity are theoretically relevant, more robust, randomised controlled trials with longer follow-up periods are needed before these medications can be recommended as a standard treatment for binge eating disorder in clinical practice.

Who Might Benefit From GLP-1 Treatment for Binge Eating

Whilst GLP-1 receptor agonists are not currently licensed for binge eating disorder in the UK, certain patient groups might potentially benefit from these medications when prescribed for their approved indications, with the additional observation of improvements in eating patterns. Clinical judgement and individualised assessment are essential when considering any pharmacological intervention.

Patients who might be considered for GLP-1 therapy (within licensed indications) and who may experience secondary benefits for binge eating behaviours include:

-

Individuals with binge eating disorder and type 2 diabetes, where GLP-1 agonists address the primary diabetes indication whilst potentially helping with eating patterns

-

Those with BED and obesity who meet NHS eligibility criteria for weight management medications (as defined by NICE TA875 for semaglutide or TA664 for liraglutide, which are narrower than the marketing authorisation)

-

Patients who have not responded adequately to psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and who have concurrent metabolic conditions

-

Those experiencing significant food cravings and loss-of-control eating as part of their weight management challenges

However, important cautions and considerations apply. GLP-1 medications may not be suitable for individuals with:

-

History of pancreatitis (not recommended per UK SmPCs)

-

Severe gastrointestinal disease or gastroparesis (caution advised)

-

Diabetic retinopathy, particularly for semaglutide (requires monitoring)

-

Pregnancy, planning pregnancy, or breastfeeding (contraindicated; for semaglutide, a 2-month washout period is recommended before conception)

-

Certain eating disorder subtypes, particularly those with purging behaviours or severe restriction

Any decision to prescribe GLP-1 agonists should involve multidisciplinary input, ideally including endocrinology or weight management specialists, mental health professionals with eating disorder expertise, and the patient's GP. Psychological support should continue alongside any pharmacological treatment, as medications alone do not address the underlying psychological, emotional, and behavioural factors that contribute to binge eating disorder. Patients should be monitored regularly for both therapeutic response and potential adverse effects, with treatment adjusted or discontinued if benefits are not evident or tolerability issues arise.

Potential Side Effects and Safety Considerations

Gastrointestinal adverse effects are the most commonly reported side effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists, occurring in a significant proportion of patients, particularly during treatment initiation and dose escalation. These include:

-

Nausea (affecting 20-40% of patients, though often transient)

-

Vomiting and diarrhoea

-

Constipation

-

Abdominal pain and bloating

-

Reduced appetite (which, whilst therapeutically desired, can occasionally be excessive)

These effects typically diminish over several weeks as the body adjusts to the medication. Starting with lower doses and gradually titrating upwards, as recommended in prescribing guidelines, can help minimise gastrointestinal symptoms. Patients should be advised to eat smaller, more frequent meals and avoid high-fat foods, which may exacerbate nausea.

More serious but less common adverse effects require clinical vigilance:

-

Pancreatitis: Patients should be counselled to stop the medication and seek immediate medical attention if they experience severe, persistent abdominal pain radiating to the back

-

Gallbladder disease: Rapid weight loss associated with GLP-1 therapy may increase cholelithiasis risk

-

Hypoglycaemia: Particularly when used alongside insulin or sulphonylureas in diabetes management

-

Diabetic retinopathy: Semaglutide requires caution in patients with pre-existing retinopathy, who should be monitored regularly

-

Renal impairment: Dehydration from gastrointestinal side effects may affect kidney function

Specific considerations for individuals with eating disorders include the potential for GLP-1 medications to exacerbate restrictive eating patterns or mask hunger cues in vulnerable individuals. There is limited data on the psychological impact of these medications in people with current or historical eating disorders. Mental health monitoring should be integral to treatment, with particular attention to mood changes, as some patients report depressive symptoms, though causality is not established.

Patient safety advice includes contacting your GP or healthcare provider if you experience persistent vomiting preventing fluid intake, severe abdominal pain, signs of pancreatitis, or any concerning symptoms. Regular follow-up appointments are essential to monitor treatment response, side effects, weight changes, and psychological wellbeing. Patients should never adjust doses without medical guidance, and treatment should be reviewed if side effects significantly impair quality of life. Suspected adverse reactions should be reported via the MHRA Yellow Card Scheme.

Alternative Treatments for Binge Eating Disorder in the UK

Psychological therapies remain the first-line, evidence-based treatment for binge eating disorder according to NICE guidelines (NG69). NICE emphasises that medication should not be offered as the sole treatment for binge eating disorder. The most extensively researched and recommended approach is:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders (CBT-ED): Typically delivered over 16-20 sessions, this structured therapy addresses the thoughts, beliefs, and behaviours that maintain binge eating. CBT-ED helps patients develop regular eating patterns, identify triggers, challenge unhelpful cognitions about food and body image, and develop alternative coping strategies.

-

Guided self-help based on CBT principles: For those with less severe presentations, structured self-help programmes with support from a healthcare professional can be effective and are more readily accessible.

-

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT): This approach focuses on relationship difficulties and life transitions that may contribute to binge eating, and has demonstrated efficacy comparable to CBT in some studies.

Pharmacological alternatives that have evidence for binge eating disorder include:

-

Lisdexamfetamine: Licensed in some countries specifically for moderate-to-severe BED in adults, though it is not licensed for this indication in the UK and is not recommended by NICE for BED. In the UK, it is primarily prescribed for ADHD and requires specialist initiation and monitoring.

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): Antidepressants such as fluoxetine or sertraline may help reduce binge frequency, particularly when depression or anxiety co-exists, though they are used off-licence for this indication.

Multidisciplinary support is often beneficial and may include:

-

Dietetic input to establish regular, balanced eating patterns without restrictive dieting

-

Support groups and peer support through organisations like Beat (the UK's eating disorder charity)

-

Treatment of co-occurring conditions such as depression, anxiety, or ADHD

-

Weight management programmes if obesity is present, delivered sensitively to avoid exacerbating disordered eating

Access to eating disorder services varies across the UK. Patients should initially consult their GP, who can refer to local NHS eating disorder services, community mental health teams, or specialist weight management services as appropriate. Private treatment options are also available. Early intervention improves outcomes, so individuals experiencing recurrent binge eating episodes should seek help promptly rather than waiting for the problem to become severe. Urgent referral is needed if there are signs of medical instability, severe psychiatric comorbidity, or suicidality. Recovery is possible with appropriate, evidence-based treatment tailored to individual needs.

Scientific References

- Ozempic 0.5 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC).

- Ozempic EPAR - Public Assessment Report.

- Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. NICE guideline NG69.

- Improvement in binge eating in non-diabetic obese individuals after 3 months of treatment with liraglutide - A pilot study.

- GLP-1 medicines for weight loss and diabetes: what you need to know.

- Tirzepatide for managing overweight and obesity. Technology appraisal guidance TA1026.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are GLP-1 medications approved for treating binge eating disorder in the UK?

No, GLP-1 receptor agonists are not currently licensed or recommended by NICE for binge eating disorder. Any use for this condition would be off-label and should be under specialist supervision alongside psychological therapy.

What is the first-line treatment for binge eating disorder according to NICE?

NICE guideline NG69 recommends cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders (CBT-ED) as the first-line treatment, typically delivered over 16-20 sessions. Medication should not be offered as the sole treatment for binge eating disorder.

What are the most common side effects of GLP-1 medications?

The most common side effects are gastrointestinal, including nausea (affecting 20-40% of patients), vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, and abdominal discomfort. These typically improve over several weeks as the body adjusts to the medication.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript