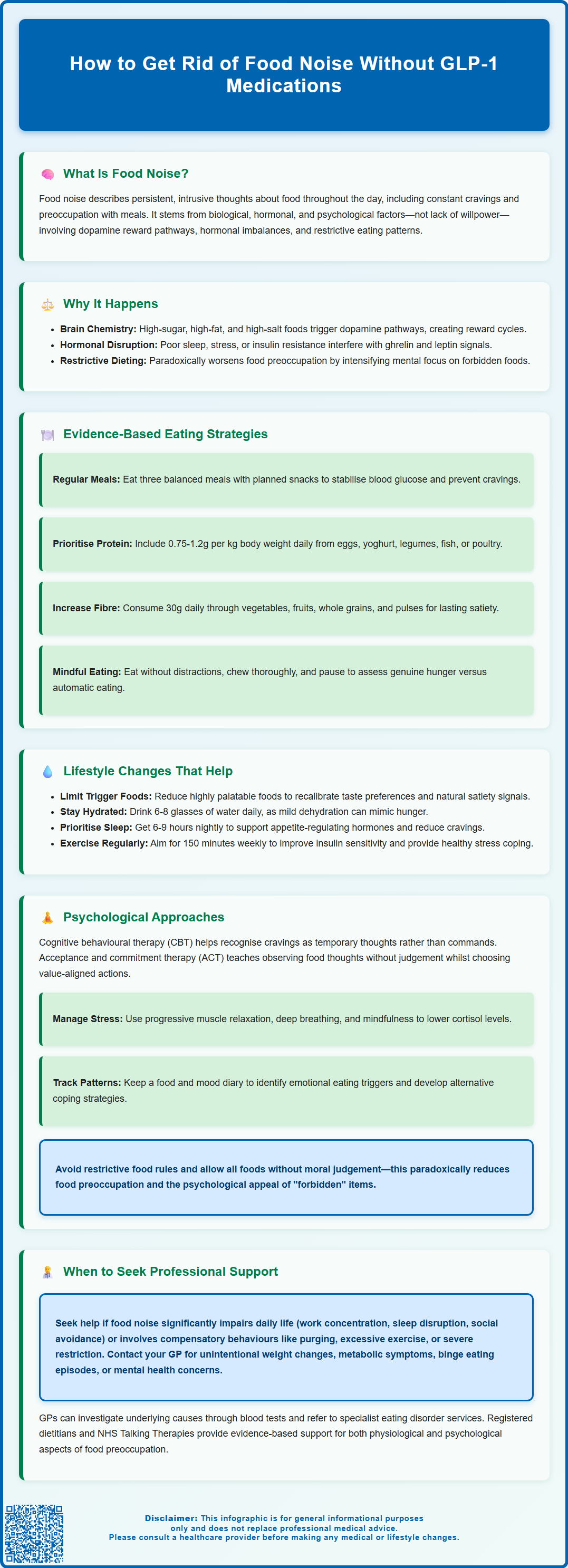

Food noise—persistent, intrusive thoughts about eating—affects many people, creating mental preoccupation that extends beyond physical hunger. Whilst GLP-1 receptor agonists have brought attention to this phenomenon, numerous evidence-based strategies can help reduce food noise without medication. Understanding the neurobiological, hormonal, and psychological factors that drive these thoughts is essential for developing effective management approaches. This article explores practical dietary, lifestyle, and psychological interventions grounded in UK clinical guidance, offering compassionate, sustainable methods to regain control over food-related thoughts and improve overall wellbeing without pharmacological intervention.

Summary: Food noise can be reduced without GLP-1 medications through structured eating patterns, adequate protein and fibre intake, mindful eating practices, stress management, and cognitive behavioural techniques that address underlying biological and psychological factors.

- Food noise describes persistent, intrusive thoughts about food driven by neurobiological reward pathways, hormonal signals (ghrelin, leptin), and psychological factors rather than lack of willpower.

- Structured eating at regular intervals with adequate protein (0.75g/kg/day for most adults) and fibre (30g daily) helps stabilise blood glucose and promotes satiety.

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) techniques can help individuals observe food thoughts without immediate reaction and challenge unhelpful patterns.

- Sleep deprivation may increase ghrelin and decrease leptin, potentially promoting hunger; NHS guidance recommends 6-9 hours nightly for most adults.

- Professional support from a GP is warranted if food noise significantly impairs daily functioning, accompanies compensatory behaviours, or is associated with unintentional weight changes or metabolic symptoms.

Table of Contents

- What Is Food Noise and Why Does It Happen?

- Evidence-Based Strategies to Reduce Food Noise Without Medication

- Dietary and Lifestyle Changes That Help Control Food Cravings

- Psychological Approaches to Managing Persistent Food Thoughts

- When to Seek Professional Support for Food Noise

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Food Noise and Why Does It Happen?

Food noise refers to the persistent, intrusive thoughts about food that occupy mental space throughout the day. These thoughts may manifest as constant cravings, preoccupation with the next meal, or difficulty concentrating on tasks due to food-related rumination. Whilst the term has gained popularity in discussions around GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as semaglutide), food noise itself is not a formal medical diagnosis but rather a descriptive phenomenon that many individuals experience.

The underlying mechanisms of food noise are complex and multifactorial. Neurobiological factors may play a role: the brain's reward pathways, particularly involving dopamine signalling, may contribute to food preoccupation, especially in response to foods high in sugar, fat, and salt. This might create a cycle where the brain anticipates reward from eating, potentially driving thoughts about food even when not physically hungry.

Hormonal regulation is also important. Ghrelin stimulates appetite, whilst leptin signals fullness. These hormones can potentially be affected by factors such as inadequate sleep, chronic stress, or insulin resistance, which might disrupt the body's natural hunger and fullness cues. Additionally, psychological factors including emotional eating patterns, restrictive dieting history, and stress can amplify food noise. Restriction often leads to increased mental preoccupation with forbidden foods, creating a paradoxical intensification of cravings.

It's worth noting that certain medical conditions (such as thyroid disorders or polycystic ovary syndrome) and some medications (including certain antidepressants, antipsychotics, and corticosteroids) can increase appetite and food preoccupation, warranting discussion with a GP.

Understanding that food noise stems from biological, hormonal, and psychological origins—rather than simply a lack of willpower—is crucial for developing effective, compassionate management strategies that do not rely on pharmacological intervention.

Evidence-Based Strategies to Reduce Food Noise Without Medication

Several non-pharmacological interventions may help reduce food preoccupation and normalise eating patterns. These approaches target the underlying mechanisms that drive persistent food thoughts without requiring GLP-1 receptor agonists or other medications.

Structured eating patterns form the foundation of managing food noise. Research suggests that eating at regular intervals—typically three balanced meals with planned snacks if needed—helps stabilise blood glucose levels and prevents the dramatic fluctuations that can trigger cravings. Skipping meals or prolonged gaps between eating episodes can paradoxically increase food preoccupation as the body enters a state of perceived deprivation.

Protein intake is valuable for satiety. The UK Reference Nutrient Intake (RNI) for protein is 0.75g per kilogram of body weight daily for most adults. Some individuals, such as older adults or those engaging in regular exercise, may benefit from slightly higher intakes (1.0-1.2g/kg/day), while athletes might require 1.2-1.6g/kg/day. People with kidney disease should discuss protein intake with their healthcare provider. Including a protein source at each meal—such as eggs, yoghurt, legumes, fish, or poultry—can help reduce between-meal hunger and food thoughts.

Fibre intake deserves equal attention. The UK government recommends 30g of dietary fibre daily, yet most UK adults consume considerably less. Fibre-rich foods including vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and pulses promote satiety by adding bulk to meals and slowing digestion. The NHS Eatwell Guide provides practical advice on incorporating these foods. Some evidence suggests fibre may support gut bacteria, which could potentially influence appetite regulation, though research in this area is still emerging.

Mindful eating practices can help some people develop present-moment awareness during meals, helping them recognise genuine hunger and fullness signals rather than eating automatically or emotionally. This involves eating without distractions, chewing thoroughly, and pausing mid-meal to assess satiety levels.

Dietary and Lifestyle Changes That Help Control Food Cravings

Beyond structured eating, specific dietary modifications can help reduce food noise. Limiting consumption of foods high in fat, salt and sugar—which can be highly palatable—may help recalibrate taste preferences. These foods can potentially override natural satiety mechanisms and contribute to cravings. The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) notes that focusing on overall dietary patterns rather than specific food processing is most important for health. Gradually replacing highly processed items with whole-food alternatives allows taste preferences to adapt over time.

Blood glucose stability is important. Meals combining complex carbohydrates, protein, and healthy fats may prevent the rapid glucose spikes and subsequent crashes that can trigger hunger signals. For example, pairing fruit with nut butter, or choosing wholegrain bread with eggs, creates a more gradual glycaemic response compared to refined carbohydrates consumed in isolation.

Hydration status can influence appetite perception. Mild dehydration might sometimes be misinterpreted as hunger. The NHS Eatwell Guide suggests 6–8 glasses of fluid daily, with water being the optimal choice. For some people, drinking water before meals may help with feeling fuller.

Sleep hygiene represents an important factor. Sleep deprivation may affect appetite-regulating hormones: ghrelin levels can increase whilst leptin decreases, potentially promoting hunger. The NHS advises that most adults need between 6-9 hours of sleep per night. Studies suggest that insufficient sleep may be associated with greater food cravings, particularly for energy-dense foods. Prioritising adequate quality sleep supports hormonal balance and may reduce food noise.

Physical activity offers multiple benefits. Regular exercise can improve insulin sensitivity, which helps stabilise blood glucose. The UK Chief Medical Officers recommend 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity weekly, plus muscle-strengthening activities on at least two days per week, and reducing sedentary time. Physical activity provides an alternative coping mechanism for stress and boredom—common triggers for food noise—and for some people, exercise may temporarily affect appetite hormones.

Psychological Approaches to Managing Persistent Food Thoughts

Cognitive and behavioural strategies can help address the psychological dimensions of food noise. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques can help individuals identify and challenge unhelpful thought patterns around food. For instance, recognising that a craving is a temporary mental event rather than a command requiring immediate action can reduce its power. Thought records and cognitive restructuring exercises enable people to develop more balanced perspectives on eating.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) principles teach individuals to observe food thoughts without judgement or immediate reaction. Rather than attempting to suppress cravings—which can sometimes intensify them—ACT encourages acknowledging thoughts whilst choosing actions aligned with personal values. This might involve noticing a craving, accepting its presence, and deciding whether eating serves one's broader health goals in that moment.

Stress management is essential, as chronic stress can elevate cortisol levels, which may increase appetite and drive preference for palatable comfort foods. Evidence-based stress reduction techniques include:

-

Progressive muscle relaxation – systematically tensing and releasing muscle groups to reduce physical tension

-

Diaphragmatic breathing – slow, deep breathing that activates the parasympathetic nervous system

-

Mindfulness meditation – regular practice may help reduce emotional eating and improve awareness of hunger cues

Addressing emotional eating patterns requires distinguishing between physical hunger and emotional triggers. Keeping a brief food and mood diary can reveal patterns where eating serves to manage difficult emotions such as anxiety, loneliness, or boredom. Developing alternative coping strategies—such as calling a friend, engaging in a hobby, or taking a brief walk—provides options beyond food for emotional regulation.

Challenging diet culture and rejecting restrictive eating rules can paradoxically reduce food preoccupation. Labelling foods as 'forbidden' often increases their psychological appeal. Allowing all foods to fit within a balanced pattern, without moral judgement, can diminish the intense focus on restricted items.

NICE guidance (NG69) recommends specific psychological therapies, including enhanced CBT (CBT-E), for eating disorders. NHS Talking Therapies (formerly IAPT) can provide access to evidence-based psychological support for many eating-related difficulties.

When to Seek Professional Support for Food Noise

Whilst many individuals can manage food noise through self-directed strategies, certain circumstances warrant professional evaluation and support. Recognising when to seek help ensures appropriate intervention and prevents potential complications.

Persistent food preoccupation that significantly impairs daily functioning—such as difficulty concentrating at work, disrupted sleep due to food thoughts, or avoidance of social situations involving food—indicates the need for professional assessment. Similarly, if food noise is accompanied by compensatory behaviours such as excessive exercise, purging, or severe restriction, this may suggest an eating disorder requiring specialist intervention.

Individuals should contact their GP if food noise is associated with:

-

Significant unintentional weight changes (gain or loss)

-

Symptoms suggesting metabolic dysfunction (excessive thirst, frequent urination, unexplained fatigue)

-

Binge eating episodes with loss of control

-

Depressive symptoms or anxiety significantly affecting quality of life

-

Previous history of eating disorders with concerning symptom recurrence

-

Thoughts of self-harm or suicide (requiring urgent help via NHS 111, A&E, or 999)

Seek urgent medical attention if experiencing symptoms of undiagnosed diabetes (extreme thirst, frequent urination, unexplained weight loss, blurred vision, fatigue).

The GP can conduct appropriate investigations, including blood tests to assess thyroid function, glucose metabolism, and nutritional status, which may reveal underlying medical contributors to appetite dysregulation. They can also review current medications, as some medicines can increase appetite. NICE guidance on eating disorders (NG69) emphasises early intervention and recommends referral to specialist eating disorder services when appropriate.

Registered dietitians, particularly those specialising in disordered eating, can provide personalised nutritional counselling that addresses both physiological and psychological aspects of food noise. They can help develop sustainable eating patterns without promoting restrictive approaches that may worsen preoccupation.

Psychological therapy through NHS Talking Therapies offers evidence-based interventions including CBT for individuals whose food noise relates primarily to emotional eating or anxiety. For more complex presentations, referral to clinical psychology or specialist eating disorder services may be necessary. Seeking support is a sign of self-awareness and commitment to health, not a failure of willpower.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you reduce food noise without taking GLP-1 medications?

Yes, food noise can be reduced through non-pharmacological approaches including structured eating patterns with adequate protein and fibre, mindful eating practices, stress management techniques, cognitive behavioural strategies, and addressing underlying sleep or hormonal factors that influence appetite regulation.

What causes persistent food thoughts or food noise?

Food noise stems from multiple factors including the brain's dopamine-driven reward pathways responding to palatable foods, hormonal signals such as ghrelin and leptin that regulate hunger and fullness, psychological patterns including emotional eating and restrictive dieting history, and physiological factors like inadequate sleep or blood glucose fluctuations.

When should I see a GP about food noise?

Consult your GP if food noise significantly impairs daily functioning, is accompanied by compensatory behaviours such as purging or excessive exercise, causes significant unintentional weight changes, or is associated with symptoms suggesting metabolic dysfunction such as excessive thirst, frequent urination, or unexplained fatigue.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript