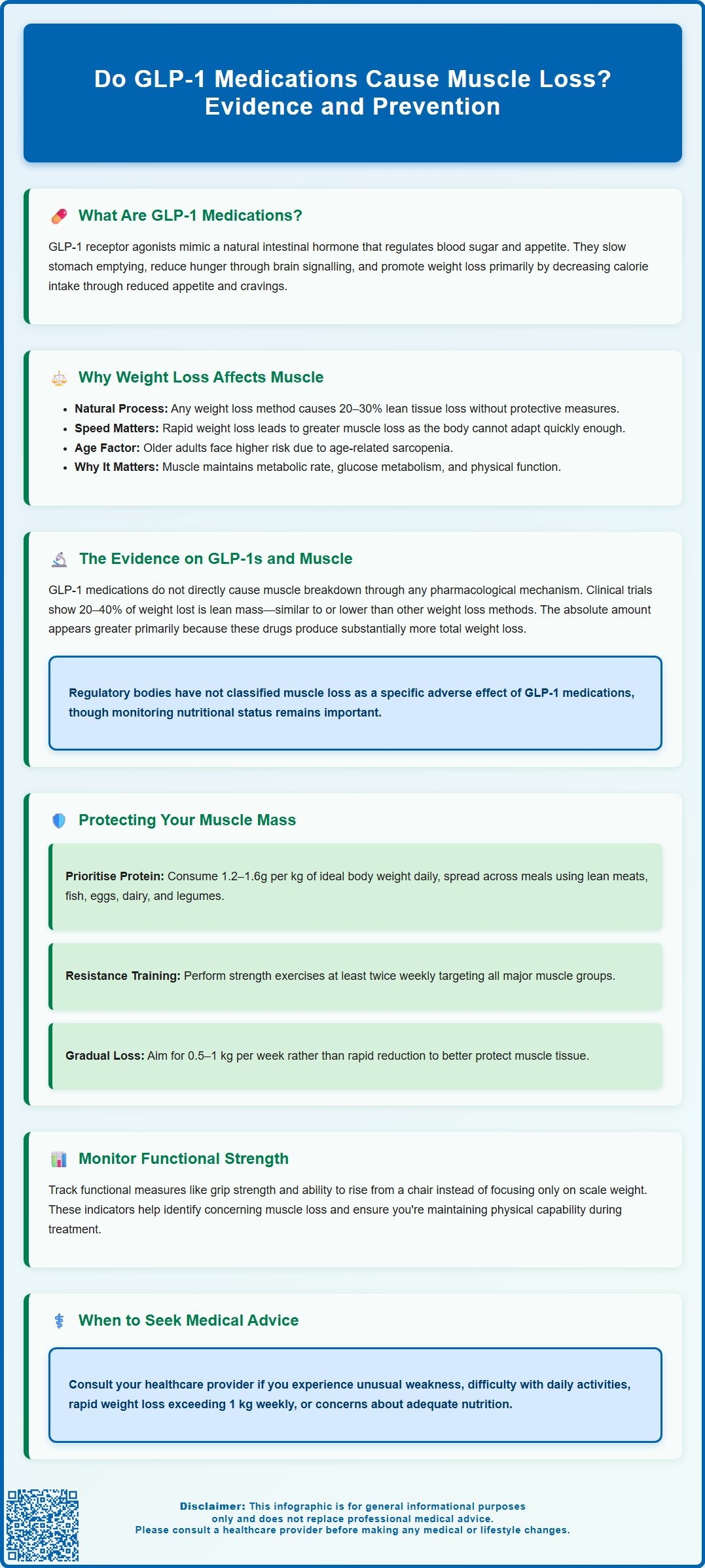

GLP-1 receptor agonists such as semaglutide and liraglutide have transformed weight management for people with obesity, but concerns about muscle loss during treatment are increasingly common. Whilst these medications do not directly cause muscle breakdown, the substantial weight reduction they facilitate does result in some loss of lean body mass—a phenomenon that occurs with any significant weight loss method. Understanding the relationship between GLP-1 medications and muscle mass is essential for patients and healthcare professionals to implement protective strategies. This article examines the evidence on muscle loss with GLP-1 therapy and provides practical guidance on preserving lean tissue during treatment.

Summary: GLP-1 medications do not directly cause muscle loss, but the substantial weight reduction they facilitate results in some lean body mass loss, similar to other weight loss methods.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists have no direct pharmacological mechanism that breaks down muscle tissue or impairs muscle protein synthesis.

- Clinical trials show approximately 20–40% of total weight lost with GLP-1 medications includes lean mass, comparable to dietary restriction and bariatric surgery.

- Muscle loss occurs as a consequence of the calorie deficit and energy restriction, not from the medication itself.

- Protective strategies include consuming 1.2–1.6 g protein per kg ideal body weight daily and engaging in resistance training at least twice weekly.

- Healthcare professionals should monitor nutritional status, functional capacity, and encourage appropriate physical activity in patients using GLP-1 medications for weight management.

Table of Contents

What Are GLP-1 Medications and How Do They Work?

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a class of medications originally developed for type 2 diabetes management. In the UK, some specific GLP-1 medications are also licensed for weight management in people with obesity or overweight with related health conditions.

These medicines include semaglutide (marketed as Ozempic/Rybelsus for diabetes and Wegovy for weight management), liraglutide (Victoza for diabetes, Saxenda for weight management), and dulaglutide (Trulicity for diabetes only). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro) is a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist currently licensed in the UK for type 2 diabetes only.

GLP-1 medications work by mimicking a naturally occurring hormone produced in the intestines after eating. This hormone has several important effects on the body's metabolic processes. Firstly, it stimulates insulin secretion from the pancreas when blood glucose levels are elevated, helping to control blood sugar. Secondly, it suppresses glucagon release, which prevents the liver from producing excess glucose. Thirdly, and perhaps most notably for weight management, GLP-1 slows gastric emptying—meaning food stays in the stomach longer, promoting feelings of fullness (though this effect may worsen symptoms in people with gastroparesis).

Additionally, these medications act on receptors in the brain's appetite centres, particularly in the hypothalamus, reducing hunger signals and food cravings. This combination of effects leads to reduced calorie intake, which is the primary mechanism behind the significant weight loss observed in clinical trials. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has approved specific GLP-1 receptor agonists for use in the UK, with NICE providing guidance on their use for both diabetes management and, in specific circumstances, for weight management.

Key mechanisms of GLP-1 medications:

-

Enhanced insulin secretion in response to meals

-

Reduced appetite through central nervous system effects

-

Delayed gastric emptying, promoting satiety

-

Improved glycaemic control in people with diabetes

Why Weight Loss Can Affect Muscle Mass

When individuals lose weight through any method—whether dietary restriction, increased physical activity, medication, or surgery—the body typically loses both fat mass and lean body mass. Lean body mass includes skeletal muscle but also encompasses organ tissue, bone, and water. This is a well-established physiological phenomenon that occurs regardless of the weight loss method employed. The proportion of muscle loss relative to fat loss depends on several factors, including the rate of weight loss, protein intake, physical activity levels, and the individual's starting body composition.

During energy restriction, the body requires fuel and will mobilise stored reserves to meet its needs. Whilst fat stores are the primary energy source, the body also breaks down some muscle protein through a process called proteolysis. Rapid weight loss is particularly associated with greater muscle loss, as the body cannot adapt quickly enough to preserve lean tissue. Research suggests that without protective measures, approximately 20–30% of weight lost during energy restriction may come from lean body mass, though this varies considerably between individuals.

Several factors influence the extent of muscle loss during weight reduction. Inadequate protein intake fails to provide the amino acids necessary for muscle protein synthesis, accelerating muscle breakdown. Physical inactivity or lack of resistance exercise removes the mechanical stimulus that signals the body to maintain muscle tissue. Age is another important consideration—older adults naturally experience sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) and may be more vulnerable to further muscle loss during weight reduction.

The clinical significance of muscle loss extends beyond aesthetics. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, contributing to resting energy expenditure, and plays crucial roles in glucose metabolism, physical function, and overall metabolic health. Excessive muscle loss can reduce metabolic rate, potentially making weight maintenance more challenging, and may impair physical function, particularly in older adults or those with limited muscle reserves at baseline. This is why preserving muscle mass during weight loss is an important clinical consideration for anyone undertaking significant weight reduction, including those using GLP-1 medications.

Do GLP-1 Medications Cause Muscle Loss?

The question of whether GLP-1 medications directly cause muscle loss requires careful examination of the available evidence. Current research suggests that GLP-1 receptor agonists do not have a direct pharmacological mechanism that causes muscle breakdown. These medications do not interfere with muscle protein synthesis or directly promote muscle catabolism. However, the substantial weight loss they facilitate does result in some loss of lean body mass, as occurs with any significant weight reduction.

Clinical trials of GLP-1 medications have consistently demonstrated that whilst participants lose considerable weight, a proportion of this weight loss includes lean body mass. The STEP (Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity) trials showed that participants lost approximately 15–20% of their body weight over 68 weeks, with body composition analyses indicating that roughly 20–40% of the total weight lost was lean mass. Similarly, trials of tirzepatide have shown substantial weight loss with a comparable proportion of lean mass reduction.

It is important to contextualise these findings. The proportion of lean mass loss observed with GLP-1 medications appears similar to that seen with other weight loss interventions, including dietary restriction alone and bariatric surgery. Some research suggests the proportion may actually be slightly lower than with very-low-calorie diets. The absolute amount of lean mass lost is greater with GLP-1 medications primarily because the total weight loss achieved is substantially greater than with diet and exercise alone.

It's worth noting that while lean mass decreases in absolute terms, the proportion of lean mass relative to total body weight may be maintained or slightly increase, as fat mass typically falls more rapidly.

Key evidence points:

-

GLP-1 medications do not directly target or break down muscle tissue

-

Lean mass loss occurs as a consequence of the calorie deficit and weight reduction

-

The proportion of lean mass lost is comparable to other weight loss methods

-

Greater absolute lean mass loss reflects the greater total weight loss achieved

Regulatory bodies including NICE and the MHRA have not identified muscle loss as a specific adverse effect requiring special warnings in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs), though healthcare professionals are advised to monitor nutritional status and encourage appropriate dietary protein intake and physical activity in patients using these medications for weight management.

How to Protect Muscle While Taking GLP-1 Medications

Preserving muscle mass whilst taking GLP-1 medications requires a proactive, multifaceted approach. Healthcare professionals and patients should work together to implement strategies that protect lean body mass during weight reduction. These evidence-based interventions can significantly reduce the proportion of weight lost from muscle tissue.

Optimise protein intake: Adequate dietary protein is fundamental to muscle preservation. Current evidence suggests that individuals losing weight should consume 1.2–1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of ideal body weight daily, distributed across meals. High-quality protein sources include lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, and plant-based alternatives. For someone with an ideal body weight of 70 kg, this translates to approximately 84–112 grams of protein daily. Given that GLP-1 medications reduce appetite and food intake, achieving adequate protein consumption requires conscious effort and may benefit from dietetic support. People with kidney disease should seek medical advice before increasing protein intake.

Engage in resistance training: Progressive resistance exercise is the most effective intervention for preserving and building muscle mass. The UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines emphasise the importance of strength training, and NICE guidance on weight management highlights physical activity. Aim for at least two sessions per week targeting all major muscle groups. This can include weight training, resistance bands, bodyweight exercises, or functional movements. Even modest resistance training can significantly reduce muscle loss during weight reduction.

Maintain gradual weight loss: Whilst GLP-1 medications can facilitate rapid weight loss, a more gradual approach (around 0.5–1 kg per week) may better preserve muscle mass. Some healthcare professionals may consider individualised dose titration strategies that balance effective weight loss with muscle preservation, particularly in older adults or those with limited muscle reserves, though evidence specifically for this approach is limited.

Monitor functional capacity: Rather than focusing solely on scale weight, tracking functional measures such as grip strength, ability to rise from a chair, or everyday activities can help identify concerning muscle loss. If available, bioelectrical impedance analysis might provide additional information, though these measurements have limitations.

When to seek medical advice:

-

Experiencing unusual weakness or fatigue beyond initial adjustment

-

Difficulty performing usual daily activities

-

Concerns about nutritional adequacy

-

Rapid weight loss exceeding 1 kg per week consistently

Your GP or prescribing clinician can provide personalised guidance, potentially including referral to a dietitian or exercise specialist. Regular monitoring appointments should include discussion of dietary intake, physical activity, and functional capacity to ensure weight loss remains healthy and sustainable.

If you experience any suspected side effects from GLP-1 medications, report them to the MHRA Yellow Card Scheme (yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk).

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you prevent muscle loss whilst taking GLP-1 medications?

Yes, muscle loss can be minimised by consuming adequate protein (1.2–1.6 g per kg ideal body weight daily), engaging in resistance training at least twice weekly, and maintaining a gradual weight loss rate of approximately 0.5–1 kg per week.

Is muscle loss with GLP-1 medications worse than with other weight loss methods?

No, the proportion of lean mass lost with GLP-1 medications (approximately 20–40% of total weight loss) is similar to other weight loss interventions including dietary restriction and bariatric surgery. The absolute amount may be greater simply because total weight loss is substantially higher.

Should older adults be concerned about muscle loss with GLP-1 medications?

Older adults may be more vulnerable to muscle loss due to age-related sarcopenia and should work closely with healthcare professionals to implement protective strategies, including adequate protein intake, resistance exercise, and monitoring of functional capacity throughout treatment.

The health-related content published on this site is based on credible scientific sources and is periodically reviewed to ensure accuracy and relevance. Although we aim to reflect the most current medical knowledge, the material is meant for general education and awareness only.

The information on this site is not a substitute for professional medical advice. For any health concerns, please speak with a qualified medical professional. By using this information, you acknowledge responsibility for any decisions made and understand we are not liable for any consequences that may result.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript